The Wild Place

Essay by Carolyn Kuebler | Photography by Corey Hendrickson

Look, I’m alive. And this park, Wright Park it’s called — a scrappy woodland just a half mile down the road from my home — is alive too, living and dying at once, whether I’m there to see it or not. It is not an old-growth forest, not a mountainside, there’s no grand vista, nor really complete immersion in its 150 acres. I can often hear train cars groaning and bashing up against each other, or mysterious industrial sounds from the other side of the tracks that border the park: the cheese factory, the brewery, the Feed & Farm Supply. It’s the outskirts of the outskirts. A nothing kind of place at the end of a nothing kind of road where one small town gives way to an even smaller one.

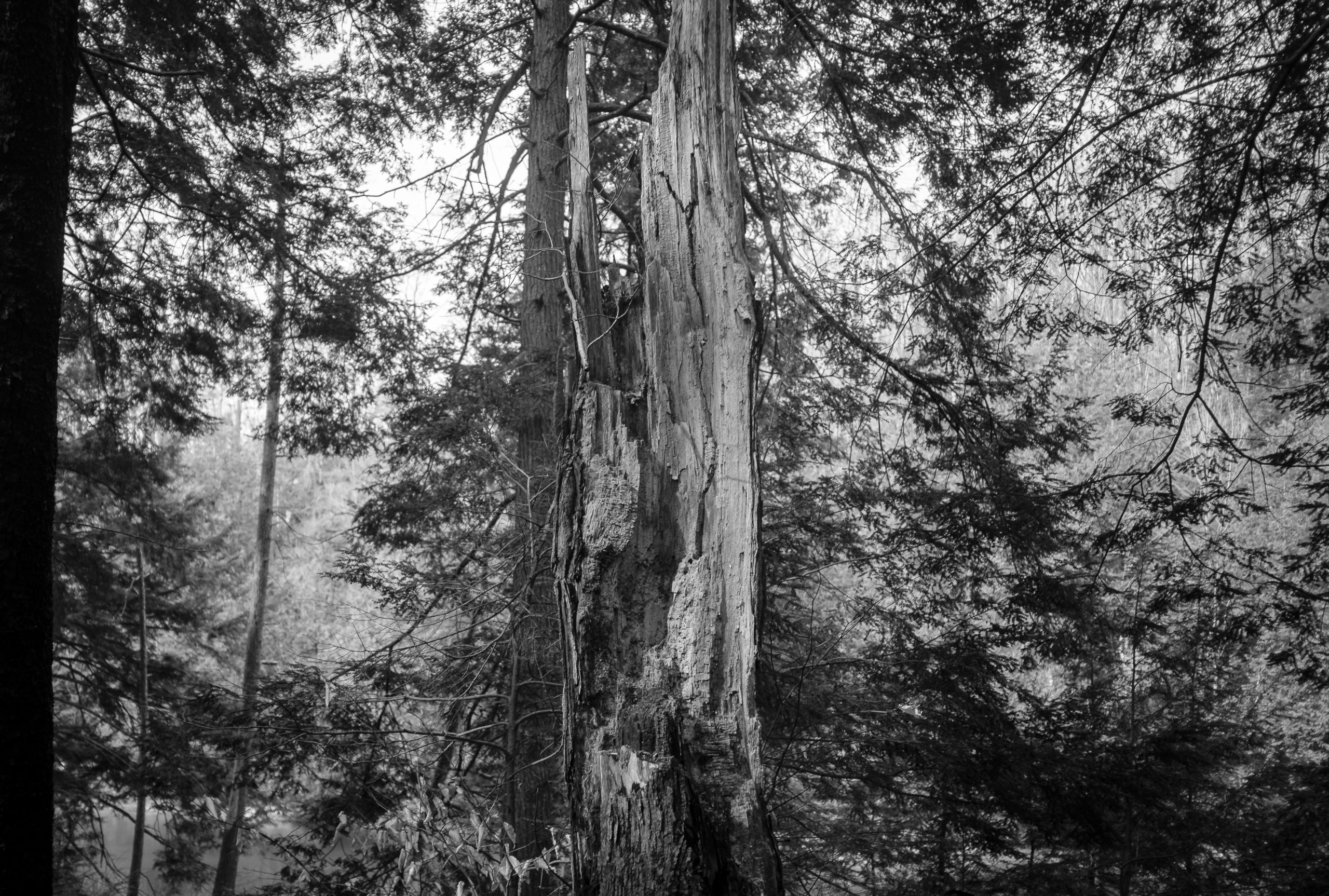

For 15 years I’ve known of this park, spent more and less time in it. But where the park renews every spring, I — a single specimen, like a single tree — only decay.

And yet a partially dead tree is layered with life, even more than a young, fully alive one. Whereas a young tree is all surge and green, an old one, with its dead limbs and deep roots, is home to mosses, fungi, insects — intricate systems we can’t even see. But some that we can see too: hollows turned to squirrel nests, dead limbs drilled by woodpeckers. The old tree both lives and dies and is all the richer for it, having so much to give away.

When I was younger and lived in cities, I’d gravitate toward some illusion of solitude in nature and thrill at the first hint of it: Allentown’s Cedar Beach, Lake Harriet in Minneapolis, the far end of Red Hook in Brooklyn, where you could hear the lapping of the East River against the pilings in the quiet, cobbled streets. And yet I rarely seemed to have time to visit Wright Park, right down the road. Or any park really, these past 15 years, these middle years, the time of life when there’s just no time.

But in spring of 2020, social occasions, arts events, school, travel, even walking back and forth to work — all dropped off the books. Hopefully laid plans were disassembled, one piece at a time, as everything closed down. Reading the news from New York City, where the coronavirus was surging most gruesomely, I almost wanted to be there in the middle of it, to hear the sirens all night long. Walking down an empty street in Middlebury, I’d have to remind myself, say it out loud — it’s a pandemic — in attempt to dismantle my disbelief, even as hospitals and colleges, the National Guard, everyone, was preparing for a surge in patients.

At the same time, the radical simplifying of daily life was such a relief. In other places, immediate death and devastation. Here, a kind of blessing. Such deep contradictions. I took them to the park with me.

Preppers and Poets

Just a few houses down from mine, if you veer right onto the street’s “extension” rather than follow the main road around the curve into the covered bridge and walk about a half mile — ten minutes there, ten minutes back — you get to the secluded entrance to the park.

The real estate agent called this area a “transitional neighborhood” and tried to warn us away from it. The homes here are not good old homes, restored and restorable, and they’re not good new homes either. There’s no harmony to the patterns they establish up and down the road.

The extension begins with a trailer, abandoned and slowly sinking into the ground, and continues with a tidy little prefab with a picket fence and sentimental statuary, an aluminum storage bunker for the trash pickup company, and a cedar-shingled shed that might belong on Nantucket if not for the boarded-up doorways. There’s a striking, silver-sided house with wooden doors swinging open, and across from it a ranch house with stone-bordered gardens, a gutter-fed rain barrel, and No Trespassing signs posted on the trees. “Probably preppers,” people say.

Finally, the last building before the road turns to dirt for the final leadup to the park is what I think of as, and possibly is in truth, the “poets’” house. A large round window looks out from the second story onto the rusted ice-cream parlor furniture planted in the yard. It’s in bad need of paint.

The last quarter-mile stretch, with a thin row of young spruce trees between it and a massive stump and gravel dump, is a dead end that leads straight to the trailhead. Wright Park.

Cruelest Months

Dreary with a hint of snow. That’s how spring arrives in Vermont, and it was no different this year. I wasn’t walking to work, so I walked in the park instead. In March into April, the trees were beginning to wake up — as if lightly brushed with gold and pink — but there were still patches of snow in the otherwise cold, flat, and faded woods.

Then at the end of April, something broke through. Tiny, yellow, nodding flowers. What were they called again? I’d noticed them last year, looked them up, tried to memorize them. Trout lily!

I was so pleased to see them, but maybe even more pleased that I could recall the name. And it dawned on me, finally, why the name “trout”! The leaves are smooth, spotted brown and green, like a brook trout, and shaped something like one too — not named for the flowers at all. Once I saw them, they were everywhere, pushing their way out from under the matted dead leaves.

Looking for trout lily I started to see other flowers, too. A small cluster of white blossoms, each no bigger than a fingernail, with a ring of delicate stamens that made it look decorated with the tiniest paintbrush. Then I saw pink ones, otherwise identical to the white, and as if that weren’t enough, also deep lavender. Each with the same basic design and growing so close to the ground I had to crouch down to look at their faces or gently tilt them upwards. I’d never seen these before and so looked them up in a field guide when I got home: hepatica.

Hepatica? However would I remember that?

Trillium I already knew but was no less delighted to see. When I went to college near here, I was introduced to the white and red varieties by a friend — a new friend at the time, now a lifelong friend. In my mind she knew everything about the woods, and I followed her out one night to sleep under the moon at the top of the Middlebury Snow Bowl. The sky was thick with stars, so close. I was sure I could see the curve of the Earth from there, and I wanted my whole life to be like that: unprotected under a shining swath of the Milky Way, just scared enough to be exhilarated, not alone but gloriously free.

My whole life didn’t turn out to be like that, and yet that moment remains, underneath all these years and all these springs come and gone. It is still part of me, like one thin layer of geologic time in the Earth’s crust. Everything was still possible then. The trillium remembers. I remember.

No Camping, No ATVs

Wright Park? Oh, yeah. That place is creepy. That’s what people say, and they’re not wrong.

It may have something to do with the “transitional neighborhood” that is its runway. The slouchy trailers. The bearded men who never look up. Or maybe it’s the No ATVs sign at the gate, which is shot through with holes. Maybe it’s also the sign itself, Wright Park, which for years was graffitied with white spray paint, cleaned up, graffitied again. Then there are the cars at the end of that dead-end road: sometimes occupied and idling, sometimes empty and possibly abandoned. Sometimes there’ll be somebody sleeping inside with the windows open. Sometimes two people in the front seats play loud music. These are more often sedans with no hubcaps or souped-up, old-model Hondas than the Thule-racked Subarus or out-of-state SUVs you see at other trailheads. And more than once I’ve been startled by a tent in the woods, despite the No Camping signs.

One summer I’d see a man with his chihuahuas nearly every time I walked up to the park entrance — that ten minutes back and forth was as much as I had time for. He seemed to come out of his van when I got there, friendly, talking of his dog rescue and his sister who lived in town. Massachusetts plates, dark windows, two or three little dogs on leashes. He never seemed to leave. I didn’t let on how little I believed of what he was saying, just responded in kind, oh yes, my dog is a rescue too. From South Carolina. I tried not to linger but didn’t want to be unfriendly either, and then one day he was gone.

Another summer a teepee appeared, rising high up out of the field near the park entrance. Soon enough a sign: What is a teepee doing here? it said. And an explanation: A summer camp for kids. By summer’s end they’d painted the Wright Park sign in bright colors, Van Gogh–style swirls in the sky, rays of sun and dots of yellow flowers. At least I think it must have been them.

At one time in this park’s lifetime, most likely within the past twenty years or so, somebody took the time to carve and shellack a series of signs identifying different trees and other landmarks in the park. White pine, American beech, yellow birch, red cedar. There’s also a sign for beaver activity, which must at one time have pointed to a chewed-out tree, long gone. I imagined a retired man, a science teacher maybe, in his basement workshop. Someone who spent time birdwatching in these woods, or someone with a new tool and a need to use it. The signs are screwed into the trees they label. Some have fallen since their original placement and have been fixed to posts instead. This park was once beloved by someone who wanted us to be able to identify the trees.

Yet still there are the trash bags that pop up along the road like mushrooms. An air conditioner. An ever-renewing array of fast-food wrappers and bright blue Bud cans. The barbed-wire fence along the road, falling down and rusty, protecting what from whom?

By late spring this year it had changed. Piles of gravel appeared along the trail, as if by magic. Wheelbarrows, tipped up and waiting, like dabbling ducks. Fresh boards were placed over the muddiest spots, and the earth underfoot was worn smooth, dry, and starting to crack. The park had become a popular escape for people who would normally be in an office or a school, and it had begun to feel almost suburban. The trail crews were out in force. I never saw them; they must’ve been there weekdays while I was working inside at the computer. Evenings, I’d see the same people with their dogs — two beautiful Siberian huskies, one with a young man, one with a woman about my age. New patterns were forming. The park was going through a renaissance of sorts. New signs appeared, asking for donations. Enjoying the trail? Contribute here!

Yet the barbed wire still hid in the brush at the edge of the road. The No ATVs sign was still shot with holes.

Spadix and Spathe

Even in suburbs and cities, it’s not hard to spot an owl — particularly the fairly common saw-whet owl, so the birding blogs say. Just follow these five tips! But I’ve been scanning trees for chalky poop and peering into cedars for years, it seems, and have never seen one. Maybe I’m just better suited to wildflowers. They hold still, and they reward the habit of looking at the ground.

And yet even some plants seem to camouflage themselves, or they blossom only briefly. You have to be there on the right day or the flower is gone. Take the jack-in-the-pulpit. Every time I go into the woods in spring I look for trillium, and I usually see them, but I’d never seen jack-in-the-pulpit. It’s such a strange flower; how could I miss it? The flower is a sturdy brown tip — Jack — popping out of a pale burgundy and green striped tube that opens out into a draping hood. Jack and his pulpit are spadix and spathe, so my book tells me, and the pictures show the blossom up close, at ground level.

It turns out that this preacher hides under a canopy of his own leaves, which are the far more obvious part of the plant, and the part most pictures leave out. The blossom itself is short-lived, eventually turning into a cluster of bright red berries. It wasn’t until last spring, after walking and scanning the ground every day, that I finally saw one, then two, then three! At last, there they were, another gift from the plant kingdom! It was as if a secret world were waving hello, briefly, before disappearing again.

When the woods are still a canvas of browns and grays, it’s easy to notice the new flowers as they bloom if you keep your eyes on the ground. In flat muddy areas that would later fill in with water or grow dense with green, I saw clusters of deep golden-yellow blooms: marsh marigold. On the trail itself, there one day and gone the next, were tiny purple airplane-shaped flowers with fringed tails, in patches of shiny green leaves: polygala. A little later, and a little deeper in the woods, were plentiful pink flowers, hiding in shrublike green, which I could never quite identify. Wild geranium, musk mallow — they didn’t exactly match any of those. And what were those enormous green balls that looked like they may burst any moment into white flower? They were probably great angelica or sarsaparilla. I’d never seen them before, and I only saw them that once.

It’s not enough for me to see a flower, look it up, find its name — like the vocabulary of a new language, it’s lost as quickly as it’s acquired. The next time out I still know nothing. What’s worse is that sometimes more than one plant answers to the same name, and often there’s more than one name for the same plant. Some don’t seem to have names at all or seem to have combined the traits of more than one plant so as to have become unidentifiable.

A handful of wildflower names, though, are so common that I learned them when I learned to speak — dandelion, daisy, violet. Others I’ve acquired just by living here — Joe-Pye weed, burdock, and yarrow. Indian pipes. My daughter raised an eyebrow when I pointed them out in the shade. Who named them that? They’re a strange, waxy white — stems, flower, and all. Saprophytic, they make food from dead leaves instead of the sun.

Common names are like stories, condensed and passed down, altered by time, suggesting whimsical likenesses or remedies for ailments. Another common name for the lovely hepatica, for instance, is liverleaf or liverwort, as people once thought it was good for the liver. Common names are a useful shorthand, nicknames that are neither correct nor incorrect, so why not give this colorless Monotropa uniflora, these “Indian pipes,” a new one, one that doesn’t suggest that native people are mythical and magical beings from the past, one that won’t make my daughter cringe? Yes, let’s call them ghost bells. See them there, at the foot of that dead tree, in the shade? Ghost bells.

Permanent Residents

About a quarter of the way along the trail between the road and the falls at the other end, one of those handmade wooden signs says “Sumner Homestead Circa 1875.” The tree growth is pretty thin here, and you can imagine pastures once spread out below the trail. There’s even a scrap of an old stone foundation hiding just off the trail’s edge.

It would come as no surprise to anyone living around here that at one point, between the time of the Sumner Homestead and the current park, this piece of land was owned by Joseph Battell. He has an interesting story, for sure, but the reason we remember him is that he was here when huge swaths of land were available for a dime, and he had the money to purchase them and enough respect for the natural landscape to give them away for conservation. A whole block of the downtown is named after him, as is a trail in the town of Lincoln, a twelve-thousand-acre woodland in the Green Mountain National Forest, and a sprawling dorm at Middlebury College.

This same Joseph Battell bought the 138-acre Sumner farm and then another 6.5 acres next to it in 1907. When he died in 1916 he left this, and massive amounts of other land (notably the Bread Loaf Wilderness), to Middlebury College. The college kept Bread Loaf but sold much of the rest, including the Wright Park parcel, which was sold in 1917 for agricultural use to Erwin Piper, who sold it to Nichols, who sold it to the Bergevins, and so on, until the early 1980s when the land was donated to the town of Middlebury. “The Board of Selectmen at the time of the donation questioned the purpose and usefulness of this donation; however, the donation was still made to the town,” notes the Middlebury Area Land Trust website.

According to the agreement, the town can’t build on it, can’t even turn it into a proper recreational park with a baseball diamond and basketball court. There’s a lot of land like this in Vermont, part of the plan established back in the 1960s to attract tourists, to preserve the state as a place apart from the hustle. But indeed, what is its usefulness, and for whom?

It’s useful for the homeless who camp here, near the railroad tracks; the college students who come here for trail runs; the drug dealers who need a private place to make their sales; the people needing to get out of their homes during the COVID quarantine; schoolchildren on nature field trips; the Audubon Society and their Saturday morning bird walks; the high school cross-country team; the Siberian huskies; the chihuahua rescuer; and me. We may not fit tidily into the healthful vision of Vermont sold to tourists or even to the ethos of the nature preserve, but we’re here. And so are the rabbits and snakes and salamanders.

Who, who, who does this land belong to now?

They say there are owls living here, not that I’ve ever seen them.

There are also rabbits and squirrels, snakes and toads, which I have seen.

Squatters’ rights supersede land deeds. If you can live there, it’s yours.

So it’s their land. It doesn’t belong to the town, it doesn’t belong to “you and me” like Woody Guthrie said, it belongs to the owls, to jack-in-the-pulpit, to the mosquitoes and black flies, the marsh marigolds, and the mallows.

It doesn’t matter that the park is ascribed with a name: Wright.

Who, who, who is that?

It doesn’t really matter who Wright is or was. I’ll try not to find out, and instead pay mind to the trees, the flowers, the dirt, the river, and the ghost bells nourished by decay.

Wild Columbine

By the end of May, I started running instead of walking on the trail. That way I could get all the way to the bridge over the falls at the other end, burn up more bad energy, and fit it all into a lunch break. I’d put in the earbuds and run, barely looking at the woods at all. The rocks and roots had become just a series of obstacles.

Until I saw a tiny splash of red, just where the trail opened up to the sun at the far end. It was the astonishingly intricate blooms of red columbine. They stood there, as if to say, why have you stopped paying attention? Is your interest in this place here really that superficial?

And in case I missed them the first time, there were even more where the trees gave way to the gravel staging ground of the hydroelectric station, the spot where I usually turned around. They didn’t seem to belong there, among gravel and chain link. They were too lovely for this place, with their outer ring of red petals, like blown-glass droplets, their inner ring of fine yellow curves, thin as tissue but firm as ribbon candy. I had to stop and look, to just breathe for a minute. Why such a hurry, why was I always so insistent on keeping to a schedule — work, lunch break, exercise, and work again? I love my work, it’s important to me, but so is the world outside of it.

They’re the kind of flower that suggests a whole universe in miniature. And how easy it would have been to miss them! If we were in France, a friend once said, we’d be taking photographs.

I had my excuses, though, for not bothering with it all — the flowers, the beauty, the life that goes on in the park even as I’d stopped noticing it. The heat as May turned to June was not conducive to contemplating the delicacy and strength of wild columbine. It was the heat of long-roiling racial protest, of the global climate emergency, of human hatred, violence, suffocation, and death. Everything seemed to be happening elsewhere and yet could be felt — and even seen with just a glance at any screen — all the way out here. The summer was convulsive.

But the columbine don’t care. They don’t even care that their name — What name? We don’t answer to any name — has been coopted, for a whole generation, by the name of a high school in Colorado where a couple of boys shot and killed 15 people, including themselves.

Traveling In

I never felt I came to the park often enough over the many years I’ve lived nearby — in fact I’m still able to get lost sometimes if I go off the main path. Even so, moments of my life have been inscribed here, so that a walk in the park can also feel like paging through a diary.There’s a broken-down picnic table near the river, now barely more than a pile of loose boards, almost entirely absorbed by prolific green. When I come upon it, I remember my baby daughter in my husband’s lap. My family of three on a rare day outside in the sun. When I reach the open meadow, I see her with the fifth-graders on a school field trip for an insect hunt. They found a praying mantis here, and everyone crowded around to look. Except one boy. He marched ahead, flipping the flat stones off the path where they’d been laid to protect against erosion.

When I pick my way up a steep, uneven section of the path, I remember wanting so much to share this place with my sister—how she’d love it! And how when one day I finally did, we spent the whole time talking, not looking at all.

When the trees rustle along the road at dusk, I remember the time I heard the coyotes and picked up my pace. There was a thrill there, a recognition that my life ran parallel to the wild.

I remember one bad winter kicking snow from a footbridge in rage, and watching it dissolve into the dark water — the same bridge where I saw the marsh marigolds this summer, and then later the rare cardinal flower, a bright red spike.

And sometimes when I get all the way to the hydroelectric station, just below the Arnold Bridge, I’m just here, just now. Up above the rushing water and looking down into the loud, smashing current. How lucky is that? How lucky am I?

Still, to see the same road, the same trail, the same rocks over and over again — sometimes, oh, how dull that seems. I want to go to Morocco!

“The world is a book, and those who do not travel read only a page,” said St. Augustine.

Where mobility and world travel are tied to ambition — you follow a career, follow the money, follow your dreams — to stay can feel like a kind of failure. I rarely travel, but I’ve always been susceptible to the idea that what really matters is happening somewhere else. And will I really live here the rest of my life, in a dirty, vinyl-sided house, a half mile from a scruffy park? How dare I even imagine I’ll have that, with Covid and cancer lurking everywhere?

But “one cannot read a book; one can only reread it,” said Nabokov.

I don’t want to be the one gaping at the architecture in a beautiful new city anyway. I want to be the construction worker on a ladder calling down to the waiter in the café. I want to be integrated, to be part of a place, to have that place, this park even, be part of me.

Wendell Berry says of his own farm in Kentucky, “the place and the history, for me, have been inseparable, and there is the sense that my own life is inseparable from the history and the place.” He was born and lived most of his life in the same place, whereas I only moved here in my thirties. Still, after all this time, maybe I’m beginning to belong here — traveling in rather than traveling out.

Besides, Augustine never really said that about “reading just one page.” As one online investigator of “fauxtations” pointed out, he wasn’t all that well traveled himself. What he really wrote was more like “Our great book is the entire world; What I read as promised in the book of God I read fulfilled in the world.”

Deeds and Donations

Every state park in Vermont seems to have a story like Wright Park’s, of deeds and purchases and donations, and these lineages are dutifully described on every state park’s web page, commemorating that brief moment in the history of European occupation and settlement of the Northeast when certain men bought lots of land and then were considered philanthropic when they gave it away for conservation. But talk of permanent ownership — that’s just wishful thinking. Permanently set aside for conservation, the documents say, but it’s only as permanent as the laws that bind us, the fragility of which is written in every history book.

For the approximately 8,000 years of human habitation in Vermont prior to the arrival of Europeans — yes, 8,000 — there is little or no record of what happened here, and there are certainly no deeds of sale. The Abenaki did not necessarily have dwellings on the land that is now Wright Park, or even use it for hunting or anything else before they were nearly wiped out by the Europeans. But also, maybe they did.

The top layer of history, the past few hundred years with its deeds and names, is so brief it could be scraped off in no time. Beneath it, we don’t know. The real, long history of this place goes even further back, to the beginning of this landform as we know it, about 12,000 years ago when the glaciers drew back from the land and various species, including humans, eventually moved in.

The rock ledge I pass in every kind of weather has seen it all but is silent on the matter. It was here before Sumner, before Battell, before Wright, whoever that is. It was seen by all the animals, all the people, everyone who passed by. Is the history of the Abenaki still present on this little plot of land too? It is nowhere written, but can you feel it? Is there any way to access that past, beyond the written record?

I had a friend who said she could hear the voices of the people who’d passed by the lake before her, not words, but human sounds of joy and pain, of the transactions of every day. I try to listen, but I hear no voices. Of course I don’t hear them. How crazy is that? And yet I don’t disbelieve her.

Running Into Joy

Some days I just could not move from my screen. I did not have the energy for the park, or to listen to all that quiet. Some days I didn’t go outside at all and regretted it. Other days I compromised by putting in earbuds and listening to news podcasts. But one day I discovered that if I put on music, and ran instead of walked, stepping lightly over rocks and roots, huffing up the inclines, my whole being — my fraught relation to myself and to the present state of things — would change.

The music had to be just the right mix of familiar and new. When I would put on that playlist and begin to run, the combination of music and movement conjured up something from the deep — the anticipation or hopefulness or loss I’d felt the first time that song entered my life, piled up with the many times I’d listened afterwards, and now with this day, this park, this run. If I could push my body past thinking and worrying, and breathe deeply enough, and at the same time listen to music, there it was: ecstasy!

Sunlight can most reliably evoke that feeling of pure joy, moving in any number of ways across a landscape, across the ground at my feet, dappling over water. But it can happen in the cold and rain too, with cool skin and darkened ground. It always comes as a surprise, and always it feels like some kind of blessing, a state of pure poignancy I want never to end.

In that state, the entire world feels like a gift so abundant I could never want anything more. I bound over the boards of a small bridge, so grateful that they hold, that someone has repaired it year after year. And when I run along a flat stretch of meadow, with the waving and tossing of hundreds of seedheads, I am in awe of my own feet, with their hundreds of bones, landing just right every time.

Joy, the leavener, the motivator, the sharpened spade that loosens the soil, letting air and water in. Undeserved, but there it is.

Blake said that energy is an eternal delight, and I believe this is what he meant: this energy, this joyful desiring, gone as quickly as it comes and yet eternal.

And Rilke: “Look, I am alive . . . Overabundant being / wells up in my heart.”

By July it was green, green, green out there. The wildflowers no longer surprised the way they did in the spring against all that brown, but deep into summer they kept coming anyway: Queen Anne’s lace and Japanese knotweed, daisy fleabane, yarrow, moneywort, crown vetch, thistle, milkweed, musk mallow, wild geranium, campion, black-eyed susan, red clover, wild basil, flowering rush, thistle and common nightshade, self-heal, chicory. I continued to learn their names, even though none was quite so arresting as the first trout lily or the later columbine. So many of them were just variations on dandelions and Queen Anne’s lace — prolific enough to go unnoticed. Midsummer wildflowers reach a kind of stasis.

If I took the time to go beyond the two-mile stretch of Wright Park — to the other side of the Arnold Bridge rather than just crossing and turning around — the views were completely different. Same river, but different life. Just across that bridge, one more mile, and suddenly I saw wild forget-me-nots blossoming in the sunlight. A flock of mergansers sunning on the rocks and playing in the current. A meadow dotted with red clover.

There was one whole week I didn’t go to Wright Park at all. I was gone for ten days, and when I came back: jewelweed — everywhere!

Little orange blossoms that burst when you touch them, scattering their seed. A feast for hummingbirds, but only for a day or two. I was so relieved that I did not miss this hummingbird moment, this brief wash of orange on the roadside, the creekside, beneath the bridges, and even behind the barbed-wire fence.

I almost felt guilty. I should not have stayed away so long. To think I nearly missed this!

Productivity

A human life is small and short. And yet my own is the first thing and the last thing, every day, to me, to each of us maybe, our main preoccupying concern. What is my life, what will it become, what have I settled for, what do I still have to hope for? Some days all I want is to do little harm and find some joy, and maybe if I’m really lucky, determined, and big-hearted about it all, to do some good. Inch the needle forward. But first, do no harm. For a twenty-first-century human, it’s hard not to get stuck at that level.

In October 2020The New York Times reported that 2.5 million years of potential human life in the United States had already been lost to Covid-19.

I couldn’t help but think of how this was, at the broader and abstracted view, a good thing. The less time humans, especially Americans, spend on this planet the better. Some human civilizations may have contributed to, or at least done no harm to, the health of the planet, but I don’t think at this point we can hope for that. The temptations for more and faster and easier and shinier — they’re too great and we’re too far gone, have ruined too much.

Richard Powers’s novel The Overstory is 500 pages long and full of wonder, but the moment that keeps coming back to me is when the designer of a wildly popular and addictive video game is asked, “Does it bother you, to be such a destroyer of productivity?” And the designer looks out his window to a mountain stripped by mining and says, “It might not be so bad, to destroy a little productivity.”

Economists and actuaries place the value of a human life at about 3 million dollars apiece — or 1.1 million, depending. It’s not an easy calculation, but always it’s a positive number. Considering how much destruction a human life causes, it seems that its worth should be calculated as a cost, not an asset, on the world’s economic balance sheet.

Even so, taken up close, those 2.5 million years lost represent at least 2.5 million tragedies, each of which could break my heart. Because, in spite of it all, it’s with human beings that I’ve formed my deepest connections, and it’s through human creations — art, music, literature, laughter, celebrations — that I’ve formed my deepest sense of meaning. I don’t see any way around that. Self-hatred, repulsion at one’s human self, is the logical conclusion to any widescale observation of what humanity has wrought — and never more so, perhaps, than this summer.

And yet, what wouldn’t I do to save a human life, right in front of me? What cost is too much? At close range, it becomes utterly incalculable.

My Heroes

If all humans were more like John Lewis, the politician and civil rights activist who died on July 17, 2020, then maybe I wouldn’t take such a grim view of these numbers.

Yes, John Lewis found the right way to live. He had a purpose, his presence here on Earth was justified. Listening to a podcast about his belief in the Beloved Community, jogging along my usual path, I imagined being good as John Lewis was good. Imagined standing in the way of violence, setting myself up to be bludgeoned by a mob, the way he did, all the while holding the image in mind of these murderous armed men as innocent babies. Could I do it? Nonviolence like that, when it has righteousness on its side, is an act of bravery more powerful than anything that comes in its path.

Then two huge birds lifted off a tree. Yes, on Monday, August 3, 2020, 6:15 p.m. while I was running and thinking about John Lewis, two barred owls flew across the path right in front of me. So large I thought maybe they were turkeys. They settled on the branches above, large, staring at me.

They were like monkeys, perched up there in a dead treetop, moving their heads around in gravity-defying ways, up and down and around, even face-up to the sky. Their faces looked flat from the side, as if their profiles were cut off. Their bodies were covered in brown and white feathers. They flew across the path again and settled in the bare branches of another tree and watched me some more. I stopped and watched them back.

They were intimidating. Owls like this have wingspans of three to four feet. They eat baby bunnies. They seemed to be staring at me with their amazing, predatory vision. They could probably see the sweat on my face, though hopefully could tell from my eyes that I intended no harm.

I plucked out the earbuds and watched and listened, afraid I’d scare them away. They made some little chirpy sounds. After a while it felt rude to be staring the way I was, so I took a few steps away and watched from a greater distance while they twisted their heads around and flapped their enormous wings.

Once I finally turned and walked away, I heard them hooting. Who who who cooks for you?

Just like the books said they would.

I’d never seen a barred owl before. I’d heard of other people seeing them around here and had been jealous and a little miffed by their refusal to show up in my life. But there they were. I was startled and overwhelmed and, frankly, just so pleased, as if I’d finally been deemed worthy of their presence.

Birds are not good or bad. There’s no morality in their world. They eat tiny furry animals, snatch them off the ground midflight, and yet as a species they do no harm. They’ve shaved no mountaintops, poisoned no rivers.

Maybe it’s time to let the owls inherit the Earth. No tears need to be shed over the loss of a single baby mouse, or even 2.5 million mouse years. What value do the actuaries place on their lives? Yes, let them inherit the Earth. The mice, the owls, and the trees.

The Maker of Signs

As I moved through the park all summer, I kept thinking about those old wooden signs along the way and wondering who made them, who maintained them, repositioning them as the trees fell or the beavers moved on. Who tended to these things while I wasn’t looking?

It’s not hard to get information. Sometimes it’s harder to resist it, to keep things in the realm of imagination. But I wanted to know, so I sent an email to the organization that does the trail maintenance and just hours later I got my answer.

I had it all wrong. It wasn’t an old guy in his basement workshop who made those signs. They were made by a college student named Kate on a borrowed router. The router was loaned to her by the man who was her work-study supervisor for all four years she spent in college working on the trail — and who was the person who emailed me back.

It was about 20 years ago, so I had that part right, but I missed the most important part: this park is not just a scruffy woodland that the town sees as a dubious asset. It’s not a nowhere place that I happen to love. It has been loved and labored over for decades, by many, and in large part by this one man, John Derick, who not only loaned his router to Kate but spent years negotiating agreements for rights of way to connect Wright Park to the next farmer’s field, and so on, until it formed a 16-mile network of trails all around the town, the Trail Around Middlebury (TAM.) Not only that, but he’s been maintaining these trails with his own hands almost daily. A former plant manager for the Shoreham phone company, he has a lot of know-how with machines and wires and engineering and knows a lot of people.

As for Kate, she now works in a bird sanctuary in Montana. She made these signs, her onetime supervisor said, inspired by the Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge.

There’s a story to everything. My park, my lovely little Nowheresville park, is not just a single book, opening more each time it is read. It is more like a whole library, with volumes that can only be taken down and read one at a time.

Catalogue

I’d come to love my pocket-size wildflower book, with its clear protective cover and smell of vinyl and ink, its simple organization, its promise of beauty and knowledge. I’d be more likely to find what I was looking for on the internet, but the book brought more pleasure. Looking through its pages, I felt the way I did as a kid poring over catalogues for LEGO, and later for the clothing brand Esprit, each page imprinting itself on my mind as a kind of wish.

I also felt like I’d never see some of the flowers in that book — too showy, too rare — the way I knew I’d never acquire the fanciest LEGO sets or the easy, worldly stylishness of those teenagers in their sweaters. Purple gentian, butter and eggs, great angelica, rose pogonia, pink lady slipper, Dutchman’s breeches.

Seeing them first in the book made their appearance in real life all the sweeter. As sweet as the turtleheads, which I spotted at the edge of a wetland in late summer, when the weather was cooling and running got easier. These late-season, moisture-loving snapdragon-like flowers cluster around streambeds. Their flowerheads could be said to have an overbite, a shy demeanor, and yes, I can see it, it’s a bit of a stretch, but in a way they really are like turtles’ heads.

As August passed into September, most of the flowers had finished blooming, their stalks and leaves blending now into the background or transformed into berries. But first the New England asters would have their day. Aster blossoms are nearly the opposite of the turtleheads — bright and long-lasting, they paint whole meadows with shades of purple.They’re not showy as individuals; their beauty works more like a brushstroke across a backdrop, or the dabs from an impressionist’s paintbrush, offering a surprising contrast to the faded greens of the fields and forest in swaths of varying shades of lavender, dark purple, even magenta.

When I saw them this year it was as if my whole body bent to their beauty. They brought the bittersweet message that summer was nearly over, and at the same time were a reminder of the first time I really noticed them. It was just a couple years ago, but it was one of those rare times when inner and outer weather colluded to make me feel as if made of pure light. A powerful feeling of being, in that moment, truly myself. Seeing them this year brought aesthetic pleasure, of course, but more than that too. Each subsequent year the reflection, or even embodiment, of that earlier feeling may be a little fainter, but it lingers, breathing something more into the moment.

So when I saw them out walking this fall, on a dull, exhausted day, back and neck bent from too much time at a desk, worry over election season and unthinkable but possibly imminent futures, they reminded me of another self and another time, as the trillium do, but at closer range and in more abundance.

“It was odd, she thought, how if one was alone, one leant to inanimate things; trees, streams, flowers; felt they expressed one; felt they became one; felt they knew one, in a sense were one; felt an irrational tenderness thus . . . as for oneself.”

Yes, Virginia Woolf seems to have understood exactly.

Foliage

By the time the asters have faded, the famous foliage has too. There’s just a brief flash of red and gold — it’s the trees’ time now — before the park goes dormant until next spring. I’m terrified of the future, can barely imagine another year following this one, but at least I know that, whether I’m here or not, next spring the wildflowers will find a way to come back. I’ll go to the park in winter when it’s bleak and without light. I’ll go when it’s bright and covered in snow. And next spring the flowers will come out from under the faded, flattened leaves. First the trillium and trout lily. Next, maybe something I’ve never seen before.

This land between the river and the railroad — 150 acres of it — will keep opening like a book. Haunted, beautiful, always changing. This is my park, the one I’ve ended up with, the one I know best, and some days that’s enough.

Carolyn Kuebler is the editor of The New England Review and lives in Middlebury, Vt. This essay originally appeared as “Wildlfower Season” in the Massachusetts Review and was the winner of the John Burroughs Nature Essay Award for 2021.