A Weekend in the Saranacs

For a canoe trip that offers all of the glory of the High Peaks and none of the pain of portaging, head to the Saranac Lakes.

As the Saranac River began to bend around a turn, and we with it, the water slowly accelerated. I lost my words and our conversation slipped away. At the bow, Levi was still except for his paddle, listening with his whole body.

I was listening too. I could hear the cascade, tiny but mighty, the river tumbling into temporary chaos ahead. “Do you feel it?” I asked, j-stroking for a better view of the tongue. “Yeah,” he said.

The river was tugging us forward, beckoning toward the mouth of the small cascade—unmarked on our paddlers’ map—and the unknown. My toes were planted firmly on the floor of the boat but something welled up in my chest—an urge to leap off of a rock into deep water below. “Yeah. Wow,” was all I could muster. It had been a long time since I’d paddled whitewater and this was a delicious tease.

I quickly steered us left to the floating dock at the upstream entrance to the Upper Locks, which connect Middle Saranac Lake with Lower Saranac Lake.

While some people do paddle that Class II rapid, this weekend, I was glad not to have to navigate the drop or portage around it with our 90-pound canoe, loaded with food and gear for a weekend camping trip.

Thanks to the Saranac’s defining lock system, that weekend we managed to paddle four lakes (we could have paddled four more) without ever negotiating a rapid or carrying our canoe. We traveled at a leisurely pace—soaking up the first sunshine of summer, fishing as we paddled and leaving no good swimming spot untested.

The Best Sort of Adventure

The first time I carried a canoe, I was in the Adirondacks. I lifted it off the granite slab at the mouth of Slang pond in the St. Regis Wilderness Canoe Area during a 25-mile, two-day trip. I was a freshman at St. Lawrence University and when I saw an older girl gracefully flip an 80-pound Old Town onto her shoulders, I looked at my paddling partner and said, “I think I want to try that.”

It was staggeringly heavy, but I carried it, a little wobbly at first, a quarter-mile to Long Pond, where a classmate had to help me get it off my back (still, I think, the hardest part of carrying a canoe).

After a weekend of chilly, firelit skinny-dips, first casts with a flyrod, misty mornings with percolator coffee, and the first frost-sweetened wild cranberries, canoe tripping was, in my 18-year-old mind, solidified as the best sort of adventure.

Since that first trip, I’ve carried canoes in Maine’s Debsconeag Lakes Wilderness Area and heard wolves cry from beyond the horizon while paddling into camp in Canada’s Algonquin Provincial Park. Last May, I scored a spot on a three-week, self-guided rafting trip down the Grand Canyon with some of the same college friends who first taught me to put a canoe on my back.

Canoe tripping puts you between shores, in a liminal place where magic is at work and you’d better pay attention if you don’t want to miss it: wailing loons that dip under your boat, morning mist in the fall, a salmon jumping or a mayfly emerging, leaving its aquatic life behind with one vast, exhausting push upward and outward into flight.

At any rate, with a day off from work and the forecaster’s morning promise of the first break in the weather in three months, I decided to head west. It was a pilgrimage of sorts: the first time I’d been on a canoe trip in the Adirondacks in nearly five years, since returning to Vermont, where I grew up, after living for three years in California.

With a full thermos of coffee, Levi’s weathered Nature Bound canoe on the roof and a cooler packed with fresh produce, we drove across Lake Champlain and wound our way through the High Peaks Region, radio on and ready for an adventure.

Gritty Grandeur

“Wait, that’s it! That’s the turn!” I said, nearly choking on my coffee, a glazed buttermilk donut from a Stewart’s Shop in-hand, as we drove past the turn for Ampersand Bay, in Saranac Lake.

After a long and winding drive through the towering high peaks and along the Ausable river via Route 9N, Routes 73 and 86, we arrived in the village of Saranac Lake a little over-caffeinated and eager to get on the water.

Nestled between the McKenzie Pond Wilderness Area and the nearly kissing mouths of two large lakes: Lower Saranac and Lake Flower, the town has the gritty grandeur of a lot of Adirondack communities that have seen industries grow and fade. The iconic neon sign above the Grand Saranac Hotel rises above it all, looking out toward Lake Flower.

In 1864, the Saranac Laboratory opened in downtown Saranac Lake, the first lab built in the United States for research on tuberculosis, churning out cutting edge studies for nearly a century. Today, it’s a museum, but the grand houses, great camps, ornate facades and ice cream parlors remain. As do the guide services, a natural foods coop, and a classic dive bar, the Rusty Nail.

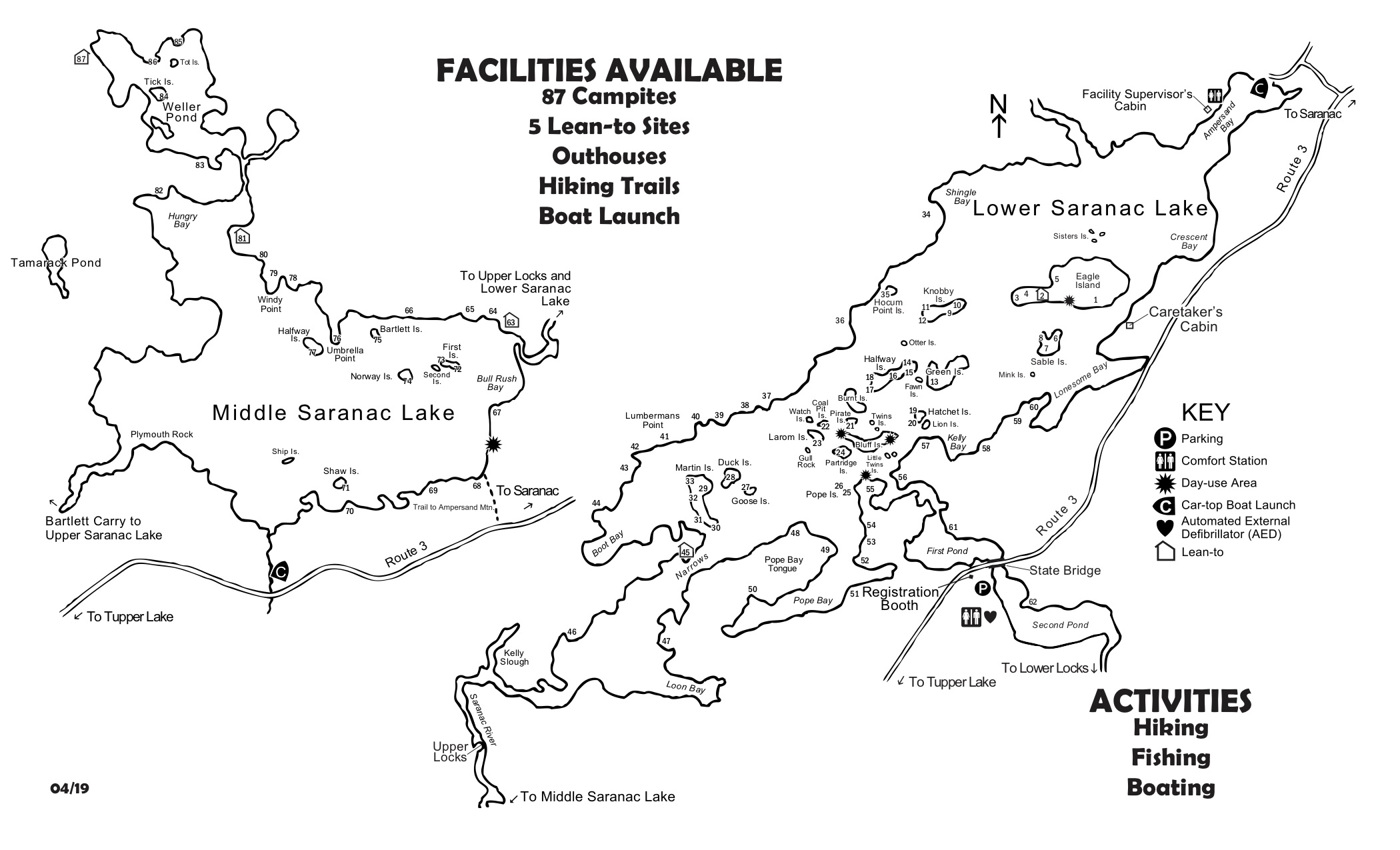

Our trip would take us from the outlet of South Creek on Middle Saranac Lake, down the Saranac River and through the Upper Locks, to Lower Saranac Lake, through its myriad islands and back to Ampersand Bay. From there, we’d leave our canoe and dry bags with a note, hop on our bikes and bike the 10 miles back to the truck on Route 3 to complete our shuttle. Then, we’d return to Saranac Lake for the boat, gear and the first ice cream cone of summer.

Glacial Remains

When we checked in at about 10 a.m. at the Saranac Lake Islands Public Campground to get our camping permit I felt like I was unfurling a lottery card. There was one site left on Middle Saranac Lake: number 74 on Norway Island. Levi looked at me and nodded. “That sounds great!” I told the ranger. We bought a pile of firewood and headed to the put-in at South Creek.

South Creek drops under Route 3 and then moves through a bog to the main lake. Black spruce, with their tall tufts of needles, dotted the bushy landscape, with cranberry, bog rosemary and Labrador tea and tufts of sedges in between. With Levi at the stern, we fell into an easy rhythm, moving as partners along a narrow channel through the brush.

As the creek became open lake, we pulled out the Adirondack Paddler’s Map North and tried to identify Norway Island amidst a smattering of 11 islands. With Ampersand Mountain looming above and the High Peaks Wilderness behind that, the scattered granite boulders and tufted islands with their rocky shores appeared like battle scars, debris carelessly tossed from on high by the same glaciers that carved the Saranac lakes some 80,000 years ago.

“Do you think it’s deep enough there to jump off of that rock?” we kept asking each other like little kids, assessing each passing mountain-torn boulder. Levi was a little more specific: “Look at that crack! What do you think about the bouldering potential?”

We paddled on for about a mile, bisecting Middle Saranac Lake and tracing the shoreline as we made our way to Weller Pond for the afternoon. As we passed Halfway Island, a woman waved to us from her perch on a granite slab, her knees cradled in one hand and a book in the other.

At that point, as we entered Hunger Bay, the lake began to constrict and the wind dropped to a gentle lull. We were quiet, basking in the summer sun and fighting private battles with the black flies that hummed around the boat.

“Do you see the mayflies?” Levi asked, making a rudder out of his paddle and looking beside the canoe.

In the shadow of the cedars that loomed over the shallows, their boughs trimmed to an even line by deer and moose, the surface of the lake was covered in wriggling nymphs. It’s hard to imagine that the thuggish looking macro-invertebrates with their hard shells and thick biceps could transform into flies. And yet, in the hot sun, we watched them take flight, delicate wings flapping frantically.

We paddled onward, fishing lazily as we went with one spin rod and one fly rod between us. From Hunger Bay, we meandered up a shallow creek that runs through yet another bog, like a trail, lined with pitcher plants, shrubs and reeds. The conversation ranged from plant identification to music theory, to our past life in California, with its high, dry peaks and vast desert wildernesses and finally to home: Vermont.

As we turned with the creek, paddling ever-so-slightly upstream, we caught a glimpse of an osprey and in the golden light, with the bog behind us and Weller Pond ahead, I had the feeling that we were coming to the edge of something.

It’s a feeling I associate with the North Woods of the East, an inexplicable thing that starts in my bones and tells me this wild place stretches into eternity; a magic trick known only by small ponds and wild bogs.

Norway Island

Norway Island—a spec of land a fifth of a mile across—appears sliced in half, with rocky tendrils shooting out into the lake on one end and a shrubby granite cliff on the other. Still marveling at our luck to have the place to ourselves, we rolled into camp. I hopped out, tied a quick bowline and started unloading dry bags. For the first time since we left South Creek, we were rushing, racing against the setting sun to set up. A cooking site with picnic tables and a fire pit sat on a rocky point facing the lake’s north shore. At the height of the island, which was covered in red and white pine, was a rocky knob that offered a window through the trees and out over the lake. Beneath the trees, we found several flat places for a tent. Down the hill there was a privy. And then, a natural pool formed by a granite boulder stacked on top of a long slab that reached out into the lake. From there, we could see Ampersand Mountain rising on the horizon, with neighboring Second Island framing the view.

As I set up the tent, still standing in my bathing suit, I said to Levi, “Can we agree that this must remain an absolutely sacred, bug-free zone?” He gave a serious nod.

Then we both pulled on pants, long sleeves and I a wool hat. We donned headlamps, grabbed the bug spray and cooler and paddled out one more time in the fading light, a Luci light in tow behind the canoe.

With the setting sun casting a glow on the mountains around us, Levi pulled out two cans of Rock Art’s session IPA from the cooler, along with some olives, chevre, crackers and, a staple of any good canoe trip: cheap cured meat.

We paddled back to our island home for a fire and dinner as alpenglow enveloped the High Peaks. Everything was pink until it was purple, and then all that was left was the crackle of the fire, a game of cribbage and the eerie, mournful calls of two loons echoing off of the lake’s many granite cliffs, so that it was impossible to tell from where or whence they came.

Heading Home

Sunday started with an early morning swim while the percolator hummed over the new MSR PocketRocket Deluxe, set to a simmer. Oatmeal was next. We set out for the day, with me at the stern and Levi at the bow.

It was a short paddle to the mouth of the Saranac River, where we met a few fishing boats trolling for largemouth bass and lake trout. We could see fish swimming in the reeds beneath our canoe as we hugged the river’s winding exterior. It was as if a channel had been cut through the heart of a grassy wetland, the forest still kept at bay while the reeds crept ever inward. About a mile into the river, an island split the stream into two channels. At the head of the island sat the lock-keeper’s cottage, a little cabin with a welcoming porch. To the right were Middle Falls, and to the left, the Upper Lock.

Middle Saranac Lake was originally called Round Lake, and it’s common to hear old-timers and guides refer to it that way still. Various structures have altered the flow from Round Lake to Lower Saranac since 1877, when a steamboat operator named William Martin built a dam in one channel and used dynamite to blast rocks out of the other. It was purportedly sabotaged by a group of disgruntled river guides, rogue woodsmen who objected to a steamboat stealing their business (they were happy to take clients down the rapids as they were).

Today, the lock is a simple mechanism: two sets of gates with long wooden beam handles sit at either end. A set of instructions is posted, along with a phone number you can call if the lock keeper is out (she was when we passed through). After much shoving and pulling on the gate beams, we filled the lock, led our canoe into it, closed the upstream gate, and started letting water out of the lower gate. Soon, with minimal effort, we were headed downstream on the Saranac River, passing beaver dams and granite cliffs.

We paddled for about a mile past banks lined with Tamarack and Spruce, until the river widened into the open water of Lower Saranac Lake. As we moved from Loon Bay and into the main lake, we avoided motor boats, sticking close to shore. It was now noon and with five miles of paddling left, we kicked into high gear and decided to skip Bluff Island, where you can find cliff jumping and a handful of established traditional climbs on south-facing granite cliffs. Second Pond, which is off of Lower Saranac Lake, also offers bouldering.

Paddling at a brisk pace, we moved between the lake’s dozen or so islands. Most are large and host several campsites. The canoeing was epically scenic, but we missed the quiet calm of Middle Saranac, where we didn’t see a single motor boat.

Party barges towed tubes, and campsites were packed with elaborate setups. “Look at us, with our canoe and our dry bags,” said Levi after one boat came by for a closer look. We’d been joking about glamping all weekend. “Next time, we need some more coolers. And bacon. We definitely did not bring enough salty pork products,” he said, with real admiration and a little longing as we passed a barbecue with peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches in our laps.

Gradually, houses started to appear along the shores, and the lake narrowed. With the wind behind us, we cruised past a marina and onto the gravel beach at Ampersand Bay. We found our old beater bikes, which we were only half-certain would be there, stashed our gear under the canoe, and embarked on a long, sweaty bike ride to South Creek, where Levi had stashed a full water bottle in the car. As he drove us back to Ampersand Bay, I stuck my bare feet out the window and watched Lower Saranac roll past, picking out islands we’d passed and singing along to Jackson Brown on the radio.

Not wanting the day to end, we stopped, canoe loaded on top of the truck, at Mountain Mist Ice Cream, a retro spot squeezed between Lake Flower and Route 86, with a vintage sign that’s almost as big as the snack bar. A burger goes for less than $7 and the chocolate dips are decadent. Sitting by Lake Flower under a Coca Cola umbrella with dripping cones, we decided three things. First, that we should have stopped at Bluff Island and could have paddled the full 20 miles from Upper to Lower Saranac had we camped at Fish Creek Ponds on Friday night. Second, that canoe glamping is a true artform that demands skill, calories and non-herbal bug spray. And third, that it was good to be back in the North Woods.

The share column blocks out some of the reading material .

Hi Marty, try reducing or enlarging the screen and that should not be a problem but if it is, let us know. What browser are you using? Thank you! Lisa