Meet 4 Pros Who Build The Trails You Love

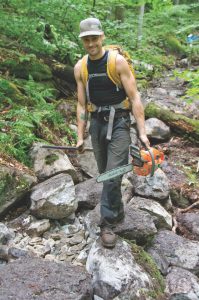

If you’ve ridden or skied any of the state’s most popular mountain bike and backcountry trails, you have a lot of volunteers to thank–and probably one of these four pros, too. Photos by Brian Mohr

They didn’t set out to be professional trail builders. Building and improving trails was simply part of the fun. Over the years, scores of anonymous volunteers have carved trails out of the hills and forests of Vermont, each riffng off what someone else had done before.

In some places, such as Pitts eld’s Green Mountain Trails, you can point to a handful of locals and folks such as Matt Baatz, who play a big role in the trail network. But no network in Vermont got to where it is today without the passion and generosity of volunteers or a local trail club coming together.

Volunteer trail building is how Knight Ide, Hardy Avery, Brooke Scatchard and Mariah Keagy all got started. All passionate riders and trail users themselves, they brought building skills and knowledge from other trades into their trail work. Now, all four are professional trail builders/ designers. They have an artillery of tools like McClouds and Pulaskis. They have an armada of excavators and other small machines, and they often work closely with teams of volunteers.

And team work is key. At Kingdom Trails, CJ Scott directs a crew of 10 dedicated individuals seasonally, May through October. They are all mountain bikers, many in high school or college, some with recreation-based college degrees.

“Our summer build season is roughly 26 weeks long, and we spend approximately $135,000 to $150,000 just in wages to maintain the system,” says Scott. “And that’s not counting materials (such as gravel or lumber for bridges), machinery (ATV/ UTV’s), chainsaws, pole saws, brush saws, tillers, soil compactors, work trucks and a wide variety of hand tools and excavators. Roughly we spend around $25,000 to $35,000 to cover those additional trail expenses.”

Yes, trail building has become a serious business. But here’s why three of the state’s top pros love it.

KNIGHT IDE: MASON AND MOUNTAIN BIKER

Having grown up in the shadow of Burke Mountain, with an affinity for gravity and speed, it’s fitting that Knight Ide launched his trail building career by helping to create a bike park on his home turf, the Kingdom Trails.

The Burke Bike Park continues to be a staple in Ide’s life. If he’s not up on the mountain coaching his IdeRide Youth Race Team or riding with friends, he’s probably tuning a few features with a tool in hand. And he does so with such passion it’s as if he is making up for lost time.

Which he is. Ide didn’t even hop on a mountain bike until he was in his late twenties. He grew up on an organic sheep farm where his parents also made candles and restored post and beam buildings.

Ide soon went to work with his father, restoring barns, churches and bridges before getting into masonry and setting up shop, Olde World Masonry, with another master mason, Dylan Eustace. The pair of stone artists now build everything from trails to bridges, fireplaces to buildings and try to keep a light touch on the land, using biodiesel to run their excavators.

Officially, the famous banked-turn Kitchel Trail at Kingdom Trails was Ide’s first paid gig as a trail builder, but he shrugs that off since he easily dedicated even more volunteer time to creating the trail.

During the last few winter seasons, Ide has been contributing to a growing trail network in Knoxville, Tennessee, which draws riders from all over the country. “But what really gets me going is when I’m building a trail somewhere I’ll be spending a lot of time…like close to home in the Kingdom,” says Ide.

As if the Kingdom hasn’t already made a name for itself with its world class riding, Ide is dreaming big. From hut-to-hut mountain bike touring, to connecting trail networks on the Burke area’s Victory Hill, Umpire and East Haven Mountains, Ide is more excited than ever to focus his energy in Vermont. Today, he works closely with his wife, Jenn, who does the books for their business, IdeRide, and runs Vermont Mountain Bike Tours with Knight’s sister, Lilias. Knight and Jenn live in Newark with their teenage son, Daymien.

Ide builds trails with both hand tools and machines, and he often works with a crew, which this summer consists of three others he has known and worked with for years: Ethan Mosedale of Barnet, Ryan McEvoy of East Burke, and Josh Gee of Andover, NH.

What inspires you most about your trail building work?

Just being in the woods is a big part of it. But trail building also allows me to be incredibly creative. Visualizing, building and then watching trails come to fruition is really energizing. I love seeing where the water’s going to go, reading the contours. I love the quiet, the birds, the trees, the smells, the solitude and the light of the forest.

What are the biggest challenges you face?

Water’s the biggest challenge, for sure. Predicting where it is—and where it wants to be—as you are designing a trail is a real challenge.

What publicly accessible projects are you working on now in Vermont? We’re just finishing another 1.5 miles of trail in Little River [State Park], which adds to the trails we built last season*. I’m also working on some new trails in the Victory Hill sector, just south of Burke Mountain. And then on East Haven mountain, where we hope to have a 2-mile descent built by the end of this season. For now, it will be a stand alone system on East Haven, but eventually we hope to connect from Moose Alley. We have a master plan that’s pretty ambitious. It’s evolving. (*While IdeRide is building the new mountain bike trails in Little River State Park, the trails were designed by Brooke Scatchard and Mariah Keagy of Sinuosity, in partnership with the Waterbury Area Trails Alliance (WATA). Funding was been made available by the VT Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation.)

How do you see the future of trails playing out in Vermont?

The possibility of connecting the many trail networks around the state really excites me, especially the potential for hut to hut and point to point riding. We have so many really good networks that enable you to go all day, but connecting them is the next step.

Do you have any advice for aspiring trail builders in Vermont?

There is a lot of criticism out there. Don’t let it get you down. Listen to it. Learn from it.

HARDY AVERY: THE TRAIL GARDENER

Hardy Avery not only designs and builds mountain bike trails for a living, but also creates backcountry ski trails and glades. When I ran into him at work one day recently he was leading a volunteer trail crew on a northeast-facing mountainside in the Brandon Gap area, and crafting a ski line that flows and drops more than 1,000 vertical feet to the stream valley below.

“This is going to be a really fun section,” said Avery, pointing to a visually pleasing swath of terrain below, sheltered by the canopy of hardwood trees overhead.

Avery’s career choice isn’t surprising considering he has spent much of his life exploring the woods, meadows and mountains of Vermont.

He grew up in Morrisville where his family created one of Vermont’s most acclaimed perennial gardens and nurseries, Cady Falls Nursery. Avery’s approach to trail building is rooted in countless mornings as a child spent shaping soil and working with hand tools at the nursery, a deep respect for the landscape, and dinner table conversations about land use laws and access issues that impacted his family, their land and their business.

After dropping out of high school, Avery went to work for, and became a part owner of the Irie (now Iride) bike shop in Stowe and helped to build many of the early trails in the area that are now managed by the Stowe Mountain Bike Club, including the original development of trails on Cady Hill, the Trapp Family Lodge land and on Perry Hill in Waterbury. For the past 10 years, he’s been building trail professionally.

What is a typical day like for you?

I tend to get on the job by 7:00 or 8:00 a.m and pound out 8-10 hours of work each day to maximize my time.

Since my services cover designing trails as well as building them, I have many days where I am out in the woods alone walking the land, documenting terrain features, hanging ags and collecting GIS data. This can take a lot of strength, both physical and mental to do well. In the case of ski trails, I will climb and descend a hillside many times a day to get just the right trail alignment. Sometimes I just don’t want to go back up but I know I need to hang a few more ags so the client can end the route or maybe I still need to walk it one more time and get a GPS track record.

Often, I will cover more than ten miles per day in rough trail-less backcountry terrain. Once this work is completed, I head home and work with my partner to create a map and a written report documenting what I laid out.

On the building end of things, on bike trails I will be running the excavator and the crew will be dong hand work or I will be doing the chainsaw work while the crew clears brush.

How does your job impact others?

I am very proud of the work I do and feel good that so many people are able to get outdoors and enjoy the forest on the trails I build. I have built trails in regions that were lacking any real organized trail network and upon completion the trails were overrun with ecstatic trail users.

As an example, I have been working with the town of Carrabassett, Maine and the Carrabassett chapter of New England Mountain Bike Association (CRNEMBA) for the past six years, designing a large mountain bike network throughout town. When I first started visiting in 2010 there were a few old trails here and there, now there is a town- wide network that is becoming a destination for riders through the Northeast. I am seeing more and more cyclists each time I visit as well as more businesses staying open year around.

We have completed a couple of public pump tracks recently, and it is amazing to see the kids swarm as soon as we open the gate. Kids on strider bikes, kids on fancy bikes, kids in bare feet, kids with no bikes just running around. Just kids sweating, breathing hard, learning to interact with each other and doing cool outdoor stuff. I just love to see these positive changes happening.

What are your favorite trail projects?

One of my favorite projects recently involved developing backcountry skiing terrain in the Green Mountain National Forest. I worked closely with some very dedicated groups including the US Forest Service, Rochester/Randolph Area Sports Trails Alliance (RASTA) and the Vermont Backcountry Alliance (VTBC), which is a part of Vermont’s Catamount Trail Association (CTA). This project, like many others I have been involved in, is located in a very rural area that is seeing an economic and population decline to the point where schools are almost closing and residents are finding it hard to stay in the area. I believe that expanding recreational opportunities can help foster a healthier community in some of our rural areas that are facing challenges.

What was your first job in the outdoor industry?

I started working in bike and ski shops as a young teen and then in my early twenties (1998) I opened my own bike shop, Irie in Stowe, with a buddy. During the nine-year run as a shop owner, I started getting into trail advocacy, maintenance and building. I come from a family of self-employed people so it never really occurred to me that I would have a normal job and boss when I grew up, I just did what I wanted to do. To a lot of people, self-employment can be scary or foreign, but if you are passionate about what you do, commit to doing good work, and there is a market for what you do, it can be a great thing.

How does someone get your job as a trail designer and builder?

There are certainly college courses focused on business, outdoor rec, forestry etc. that would prepare someone for a job like trail building. I spent a lot of time as a trail volunteer and a lot of time doing the activities that I build for. This is something that my clients see, and it allows them to trust my recommendations.

Whats the best part of your job?

I enjoy working with clients to bring their vision to reality. Most of all, I just enjoy being in the woods laying out trails, digging in the dirt and dreaming of the fun I will have once the line is completed.

BROOKE SCATCHARD & MARIAH KEAGY: INVENTOR AND TRAIL PRO

The duo behind Sinuosity, the trail development crew that’s worked on everything from private trails in North Carolina to the new town pump track at Hard’ack in St. Albans, Brooke Scatchard, and Mariah Keagy have been working on trails for nearly 20 years.

Scatchard earned a degree in geography from University of Vermont and founded Sinuosity in 2006. A former Nordic ski racer, he’d already begun work developing a “ski bike” (a fat bike with a front ski attachment) and was spending much of his time either riding or working on the trails near his home in Shelburne.

Keagy, who grew up in Dorset, started working on trails in Vermont and in the Adironcacks while still a teenager. She went on to earn a M.S in Environmental Science from Antioch New England. She’s worked on trail crews all over the United States and has served as the trails supervisor for the Appalachian Mountain Club.

The two began working together in 2013 and since then have designed and/or built many of the trails at Norwich University’s former downhill ski area, including an advanced flow trail, the Connector trail at Stowe’s Cady Hill, some of Warren’s Blueberry Lake trails and the 20-switchback Warman trail in Pittsfield.

This summer, the duo are working on a number of new trails around the state (see Fresh Dirt, p. 6). We caught up with them to learn more about the new trails—and Brooke’s side project, the Fat Bike Ski.

How do the two of you work together and what projects have you worked on?

BS: Mariah does a lot of the design and I have two other employees. We started out at Norwich University, building a full network we designed on an abandoned ski area with about 6 miles of trails, including a flow trail. We’ve built a pump track in Putney, the new Connector trail at Stowe’s Cady Hill and last summer we built Evolution, a two-mile up and down trail in the Mad River Valley.

MK: I’ve done a lot of design work and worked a lot on hiking trails. I really like to work on rock. Brooke is great at operating heavy machinery so he focuses on that.

What trails are you working on now?

BS: This summer we’ve been working on new trails near Kent Pond in the town of Killington and an entrance build near Perry Hill in Waterbury. We’re also building a flow trail at Grafton Ponds and a downhill trail network for Suicide Six.

What does it cost to build a mountain bike trail?

BS: With machines, it’s about $30,000 per mile of trail. Most people do a mile or two per year. Hand-built is a little more.

How did you come up with the idea for the fat bike ski?

BS: I started racing mountain bikes when I was 14, skied on the high school Nordic ski team and was really into metal work, so this sort of combined all three passions. I came up with the first design as my senior project at Champlain Valley Union high school. I made a prototype in shop class and applied for a patent. I even rode the prototype from Shelburne to Bolton. Interestingly enough, when I was researching the patent I found a design for a British “ice-velocipede” from the 1890s, so it’s not really a new idea.

How does the fat bike ski work?

BS: It’s a much flowier, smoother ride than a regular fat bike. The ski is on a double articulated attachment so you can both turn it and it can go up on edge and carve like a regular ski. I started out using snow blades but now have a short, wide ski custom built for this. The beauty of it is the attachment can fit onto most regular fat bike forks and it’s pretty easy to swap out a front tire. The only difference: there are no front brakes.

Have you had a lot of orders?

BS: There’s a waiting list now, and we’re gearing up our website and production. It’s about $875 for one now but I hope to get that cost down and am looking to work with a Vermont ski builder.

You still have time to build trails?

BS: Yeah, the only time I don’t ride is when trails are muddy—and I hope others don’t either because it ruins my trails.

Brian Mohr is an outdoor photographer, adventurer and writer who lives with his family in the Mad River Valley.

Pingback: Etched in Slate Valley - Vermont Sports Magazine