The New Hunters (and Why We Need Them)

As the number of hunters in Vermont declines, the sport’s veterans are working to educate a new generation to steward the land.

The air is still. In the predawn light, Heather Furman moves slowly. Layered in a mix of technical outdoor gear and rugged camouflaged clothing, she walks through the cold hollows of her Jericho Center land to the woods at neighboring Mobbs Farm.

In the silence, her slow breathing is barely audible. Beneath her feet, the leaves are brittle with frost. She makes her way to her deer stand, which she installed at a place near a small creek, at the edge of an area where there has been a recent timber harvest. She chose the location weeks prior by following informal paths and reading signs of deer—trees where the bark is scraped off, game trails. She climbs the ladder of the deer stand very slowly. With cold hands, she juggles rifle and pack. Then, seated, she waits. In the stillness, she listens while the trees creak and the forest begins to wake up. As a wood thrush launches into its two-toned, ethereal song, the dawn chorus starts.

After a long time, a deer appears, soundless. Furman’s heartbeat picks up and she breathes intentionally as she raises her rifle. Slowly, calmly, she takes aim through the sights of her gun, steadies it on a nearby branch and waits for a clean shot. After several long, cold, still minutes, the deer freezes. In the blink of an eye, it is gone.

Heather has been through this routine many times in the four years that she has been hunting. But, as she later tells me, that’s OK because “two weeks ago, after four years of deer hunting, I shot a pronghorn antelope on a trip to Wyoming.” Her patience paid off. “When I finally had the opportunity to be in that situation and actually pulled the trigger, I was calm in heart and mind and was able to make a highly accurate, instant kill.”

Furman, 48, is one of about 55,000 resident hunters in the state of Vermont and she’s an anomaly. Roughly one in four Vermont men hunt and for most, it’s a tradition passed down to them by their older male relatives. Only one in ten Vermont women hunt. Furman is also unusual in that she started hunting as an adult.

Furman started hunting grouse at the age of 36, after her husband

Dave, an upland bird hunter and former rock-climbing guide, gave her a shotgun for Valentine’s Day. After years of rock climbing together, he was hoping to include her in a sport that he was rediscovering. Shotguns are the tool of choice for bird hunting, which Heather never really took to. Four years ago, at 44, she decided to try deer hunting and, naturally, her husband bought her a rifle for her birthday.

Furman was born in Ohio and first moved to Vermont over 20 years ago to work as a park ranger at Maidstone State Park in the northeastern part of the state. She’s now the Director of the Vermont Chapter of the Nature Conservancy, which stewards 55 natural areas around the state. Fifty-four are open to hunting

Furman is a former ultra marathoner who has competed in more than a dozen ultra races, including the Vermont 50, where she had a top ten finish in 2013.

She’s also a former rock climber who has climbed at the 5.11 grade and is the cofounder of the Climbing Resource Access Group of Vermont, CRAG-VT. She served as the group’s first president for six years, from 1999 to 2005.

Furman picked up deer hunting around the time when she retired from running ultra marathons. She had grown accustomed to spending long hours at a time in the woods as a trail runner and was compelled by the growing impact of deer on the landscapes she works with at the Nature Conservancy.

Hunting is an important tool for managing Vermont’s white-tailed deer populations, which, when overpopulated, can strip a forest of its undergrowth, leaving the deer malnourished and preventing native woodland plants from establishing themselves to regenerate the forest. This is increasingly common in parts of the state as the climate warms and deer populations are no longer kept in check naturally by predators and Vermont’s harsh winters.

As Furman says, she hunts because, “I like to do my part.”

She also finds hunting deeply rewarding. “I find that my awareness of what is around me and the diversity of experiences I have in the woods are so much greater than when I was trail running with the goal of covering ground and territory,” says Furman. “Now I’m content to spend a whole day exploring a quarter-mile of forest. I couldn’t say that five years ago when I was running back-to-back 25-mile training runs on my weekends.”

The Decline of Hunting

Overall, hunting is on the decline and Furman is part of a group of new hunters working with veterans of the sport to recruit newcomers. This spring the State of Vermont hopes to roll out a new hunting mentorship program, one of a host of programs it runs to address issues like access to land and retention rates.

Since 1990, the number of hunting licenses issued to Vermont residents has declined by nearly 50 percent. In 1991, the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department issued about 92,000 licenses to residents. In 2017, the department issued just 54,836 resident licenses. That’s fewer than the department issued in 1945, when, at 315,000, the state’s population was roughly half of what it is today.

Vermont is not alone in this trend. Nationally, a report by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service found that the number of hunters in the United States declined by 11 percent between 2011 and 2016.

On average, the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife reports that roughly 15 percent of Vermonters hunt. In the Northeast Kingdom counties of Orleans and Essex, that number climbs to nearly 25 percent, close to what the statewide average was in 1974. Ninety percent of hunting carried out in Vermont is for white-tailed deer.

According to Scott Darling, Wildlife Management Program Manager for the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, that decline presents a challenge. In Vermont, hunting licenses account for roughly one third of department revenues, which fund research, conservation efforts and regulation of more than 25,000 species of fauna and 2,000 native plants. Annual license sales peaked between 1965 and 1987 but have been on the decline since. “It’s the primary funding source for the Fish and Wildlife Department as well as the match for much of the federal dollars we receive,” said Darling in October.

As Project Coordinator for the Wildlife Management Program, Darling’s colleague Chris Saunders studies the human factors involved in wildlife management. Saunders hunts and fishes with his own sons. It’s a tradition he learned from his dad, who works as a naturalist. He grew up hunting and fishing and likes to eat wild meat for health reasons and for the connection it provides him with his land. “Wildlife is extremely important to me. I birdwatch rather avidly and am a gardener too, and I don’t see a big distinction between these activities. It’s about getting intimate with nature and understanding where we belong.”

On the whole, Vermont’s hunters are an aging population. Since 2000, the number of youth hunting licenses issued to Vermont residents has diminished by more than fifty percent, from about 10,000 in 2000 to just over 4,000 in 2017. “Research has shown that people who get into hunting at an older age are less likely to keep it up over the long term,” said Saunders in October.

Saunders says that decline is due in part to Vermont’s aging demographics statewide. “Hunters by and large come from rural areas,” says Saunders. “The fewer young people you have in rural areas, the fewer young people you’re going to have hunting.”

Saunders emphasized that hunting’s decline is also due to changing social circumstances. “It used to be that if you were a rural kid, you hunted and you fished. There are more things to do now. And we know from national studies that people have less time. They are working more,” says Saunders.

Where to Find Deer?

As more areas in Vermont become developed, bubbles of posted land—places where hunters are not allowed without permission from a property owner—increase.

A study of parcelization published by the Vermont Natural Resources Council (VNRC) in early October, 2018, found that the amount of undeveloped forestland across the state decreased by 12 to 15 percent between 2004 and 2016.

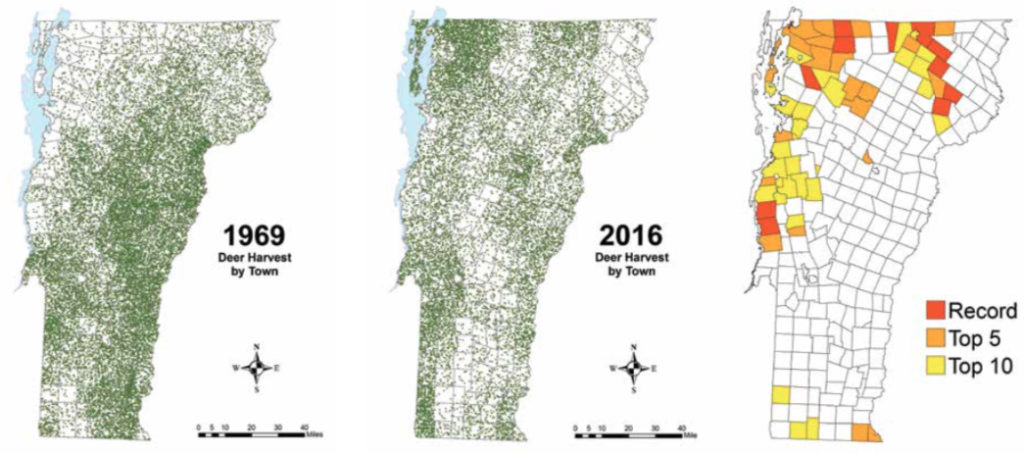

Furthermore, deer populations are highest in the parts of the state that have the most legally posted land. For example, Grand Isle leads the state in terms of deer density (30 per square mile) and also has the highest percentage of legally posted land (eight percent). Franklin County is close behind, with seven percent of its land posted and 21 to 30 deer per square mile. In contrast, as of 2016, Essex County had no posted land and a deer density of five to nine animals per square mile, well below the state’s target of 20 deer per square mile, the number biologists have determined is the maximum density that Vermont’s woodland ecosystems can sustain. Beyond that density, the natural cycle of forest regeneration is inhibited by over-grazing and deer can become pests.

In 2012, the state launched a Hunter-Landowner Connection Program, an online registry which allows landowners concerned about overbrowsing on their property to register with the State through a website. Hunters are also encouraged to register, and the state connects the two parties so that they can arrange permission to hunt.

Darling is quick to point out that parcelization is a big source of declining access. The average age of Vermont’s forest landowners is 60 to 65. “Everyone involved is worried. Will that land be passed down to their kids or sold? Will it be subdivided?” he asked.

In October, a 776-acre property, the largest remaining parcel of undeveloped land in Stowe, was listed for $10 million. “We are losing parcels like this—those over 500 and 1,000 acres—at an alarming rate,” said Furman. “Each one that is sold, subdivided and developed compromises productive intact habitat and eliminates the opportunity for traditional uses.”

VNRC’s report found that subdivided parcels are more likely to be developed and less likely to be used for forest management or for farming, uses that have supported hunting for much of Vermont’s history. As Saunders noted, “Even if land isn’t posted, you can’t hunt in a field that is now a Walmart.”

The Old Guard

When Ed Gallo was growing up in Barre in the 1970s, he says you would have been hard pressed to find a man or boy in Central Vermont who didn’t hunt. “Everybody went to deer camp. During deer season, any business that primarily depended on male labor, like construction, was totally shut down,” says Gallo. “Mom-and-pop stores would put out big signs that said, ‘Welcome Hunters’ and

churches would sponsor cheap hunter breakfasts.”

Gallo is a retired software engineer who now lives in Richmond. He is vice president of the Hunters Anglers Trappers Association of Vermont. At 61, he is part of the old guard. He learned to hunt from his father, who bought him his first gun when he was in fifth grade. He speaks poetically but practically about the land in the way of someone whose family has been tied to it for a long time.

“Hunting is not about killing the deer,” Gallo insists. For Gallo’s extended family, going to deer camp is a social affair that starts when the kids are about five or six. There’s no drinking at his camp. You get the sense that there are no cell phones either. “I know guys who are quite old and go every year but have never gotten a deer. It’s about lifelong friendships,” Gallo says. For him, learning to hunt was also about learning to be still and patient. “You spend the night at camp together, but once daylight breaks, you’re on your own. You live with your decisions and you learn to enjoy being alone in the woods.”

Gallo has no problem sharing his 120 acres with other hunters. He is quick to report poor behavior and always asks permission to hunt on others’ land regardless of whether it is posted. “When I grew up, most of the land owners were farmers and most of them didn’t have a problem allowing you on their property to cull the deer population. This is a different era and it feels like a bit of a culture clash,” says Gallo.

Vermont’s tradition of open access is as old as our statehood and was born out of a regionally distinct and very strong sense of community. Vermont has long had strict laws in place that protect property owners from liability and encourage this. However, a person who is new to a community may not have the family connections to their neighbors that were common in old Vermont and plenty of people are reasonably distrustful of gun-toting strangers.

However, according to a survey conducted by the department of Fish and Wildlife in August, 86 percent of Vermont residents look favorably on hunting. It’s also safe. Only one hunting accident involving a non-hunter has occurred since the state made hunter education mandatory in 1975.

This was confirmed by Eric Nuse, a retired Vermont game warden from Johnson. For most of his 32-year career, he was assigned to Lamoille County. He has hunted waterfowl, turkey, deer and moose in Vermont. He enjoys squirrel hunting. He grew up on a farm in Pennsylvania, where his father was a “consummate pick-up-the-roadkill kind of guy.”

At 70, Nuse is an active sportsman and serves on the Board of Directors for the New England chapter of the nonprofit Backcountry Hunters and Anglers. This year, the group is partnering with the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife to create a new hunter mentorship program. “We find we have a lot of people who didn’t come from a hunting tradition or family who take hunter education and then say, ‘what now?’” The idea is to connect new hunters and prospective mentors through weekend trainings, social gatherings and established connections to help more young people get involved with hunting. Nuse hopes the program will launch in time for turkey season next spring.

Like Gallo, he says that these trends are tied up in Vermonters’ changing social attitudes about the land. According to the Northeastern Area Association of State Foresters, 80 percent of Vermont’s forestland is held by private landowners. Of that, about 2.9 million acres, or 62 percent, is owned by families and individuals. “The old Vermont way of leaving your land open for your neighbors to recreate on is fading away. We still have a strong ethic of that in most of Lamoille County and the Northeast Kingdom. But Chittenden, Franklin, Addison? Way less so.”

Changing Climate, Changing Populations

Since 2017, the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife has been working to develop a new ten-year big game management plan for moose, black bears and deer.

Darling says Vermont’s harsh winters are no longer consistent enough to cull deer populations without human intervention as in the past. Additionally, development of previously wooded areas has allowed black bear to expand their food sources to include human garbage, and Vermont’s deer are no longer hunted by their historic natural predators—catamounts and wolves.

“White-tailed deer prefer to eat [buds and leaves of] native timber species, like sugar maples,” says Darling. “As their populations become overabundant in parts of the state, we have seen a lack of sugar maples growing in the understory. That can have a big impact on landowners managing their forests for maple products.” When deer are overpopulated, Darling says they impact other native species. “Songbirds, pollinators and butterflies are all fewer in number where there is overbrowsing of the forest understory.”

Moose have their own problems, which are exacerbated by deer overpopulation and fed by warmer winters. Citing an estimated statewide population of just 1,650 moose, in 2018 the state issued only 13 permits to hunt bull moose, and those permits were only valid in the far northeast corner of Vermont. In 2017, the statewide population was estimated to be 2,000 and 80 permits were issued. In the early 2000s, the moose population was closer to 5,000. Nuse and his wife Ingrid have been lucky to pull moose tags twice. Both times, they were successful in their hunt. He hopes that someday more Vermonters can have the same experience.

According to Darling, a study of moose calf survival rates in Vermont launched in 2017 has preliminarily found that mortality rates among moose calves in the Northeast are currently as high as 60 to 70 percent. The culprit is a parasite, the winter tick. “When we have milder falls, Winter Ticks stay out longer searching for a moose host. By winter, when moose are most vulnerable, you see as many as 20,000 to 60,000 ticks on a single animal. This fingernail-sized parasite can suck almost all of the blood volume out of a calf,” said Darling.

Making matters worse, in areas where white-tailed deer are overpopulated (more than 20 deer per mile by the state’s standards), they can transmit a parasite known as brain worm to moose. The parasite doesn’t affect deer but causes moose to appear disoriented and often leads to weight loss and death by paralysis. In short, “it’s not a good time to be a moose,” summarized Darling.

To reduce the spread of winter ticks, the department is working to temporarily limit moose populations in Vermont to one animal per square mile. Hunting is a useful tool for doing so.

The department has not yet been forced to reduce its services or programming as a result of fewer hunting license sales. However, Darling expects both the deer population and the state’s wildlife management budget will be affected shortly if younger hunters don’t emerge to replace the funds provided by the ones who are aging out of the sport. “Sadly, in other states where overabundant deer exist in localized areas, especially ex-urban areas, communities have gone to paid sharpshooters,” says Darling.

The New Hunters

For some young Vermonters, hunting is compelling because it presents a rare opportunity to unplug from today’s world of smartphones, to slow down and focus on being still. They seem to want some of the things people like Ed Gallo and Eric Nuse suggest we are all lacking: time to be still and present.

As with rock climbing, Furman says, hunting demands your full attention. “When you’re hunting, you have to find a balance between being quiet and relaxed and not doing anything but being alert to what is around you,” she says. “I don’t have a lot of quiet in my life these days. It’s a different way to be.”

For 31-year-old Kyle LaPointe, bow hunting is a quiet respite from a

fast-paced work life as a paramedic. He works long shifts to earn days off in a row, which he tries to spend outside with his kids. The rhythms of hunting suit his life as a dad better than his former passion: rock climbing.

Putting good meat in the freezer is a bonus. “I’m a foodie,” he explains. “A lot of people my age who are getting into it as adults care about conservation and where their food comes from.” That’s why he loves venison. “It’s the best meat you can get. It’s free-range, local, totally organic. I love being able to cook up intricate dishes for my whole family,” said LaPointe, who is working to recruit his wife to the sport.

LaPointe lives with his wife and three young kids on a small homestead in Townshend, Vt. He didn’t grow up in a hunting family but taught himself to bow hunt at 21, when he found himself living off the grid on a remote property in southern Vermont. He’s also a fly fisherman and cross-country skier. He primarily hunts deer on public land in Windham County.

“Archery is like the fly fishing of the hunting world.” says LaPointe. “It is very quiet. There is no bang or loud noise. You have to be very in tune with the wind and your every movement. Lots of little factors have to come into play to make a good shot.”

It also requires getting very, very close to a deer. “You have to get a lot closer to your prey in order to ethically harvest them. In Vermont, you’re talking 20 to 60 yards for a clean shot. With rifle hunting, depending on how accurate you are, you could be several hundred yards away or more.”

LaPointe is a member of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers and wishes the newly-planned mentorship program were available to him when he was learning. He killed his first deer by arrow in Vermont last year.

Like Gallo, LaPointe sees value in introducing kids to the outdoors through farming and hunting. He encourages his five-year-old daughter to practice listening and being still while they hunt grouse. “My wife and I raise and process pigs and chickens on our farm and my daughter has always been a part of that. For her, that’s where meat comes from. If she grows up and decides not to hunt and not to farm, that’s OK. At least she’ll understand that.”

A Vicious Cycle

I met Furman on a crisp day in late October at the LaPlatte River Marsh Natural Area in Shelburne. It is a perfect example of an ecosystem that has been impacted by the overabundance of deer. Oaks and beech trees abut the muddy river banks, but there is very little understory. The measured density of deer at the parcel is 32 per square mile. The target is closer to 20 deer per square mile to meet the Conservancy’s management goal: to maximize the biodiversity of native bird, pollinator and plant species there.

Deer have already impacted the forest’s ability to regenerate. Since the Conservancy’s recent effort to remove invasive buckthorn and honeysuckle cleared the forest floor, native plants have been slow to grow back. As Furman explains, the native plants they expected to replace the invasive species have been over-browsed by the numerous white-tailed deer, preventing new forest growth.

Bow hunting is allowed at the 225-acre property, which Furman describes as “a wild landscape in a suburban setting.” Hunting is allowed on all Nature Conservancy properties in Vermont. At the LaPlatte site, the Conservancy decided to limit other types of access from 3 p.m. to 10 a.m., so that hunters would have more opportunity to hunt deer during the prime dawn and dusk hours.

On our walk, we run into one local hunter, a gentleman named Ken, who has bow hunted at the preserve for 38 years. He told us he rarely sees large bucks in Shelburne anymore. “When the herd gets too big, the deer get skinnier,” he lamented. His biggest concerns? Development and parcelization. “I think we hunters all consider ourselves conservationists. When you take an animal, it’s spiritual.”

Overbrowsing affects more than just hunters. According to Furman, it can have long term impacts on forest regeneration and starts a vicious cycle. “A lot of private landowners who own larger parcels manage their woodlots for income. This problem can have long term effects on their ability to do so.” With too many deer, Foresters may find that when they harvest trees, the forest can’t regenerate as quickly. Then, without a reliable harvest cycle, the financial instability of the woodlot makes them more likely to have to sell their land and divide it.

“That impacts us from a cultural standpoint,” Furman says. “Whether you’ve lived here for a year, ten years, your whole life, the landscape and our relationship to it defines us as Vermonters. These issues affect all of us.”

Furman gestured around her. “There is a deep culture of hunting in Vermont, born from a time when a lot of Vermonters hunted for subsistence,” she said. “The culture of hunting is an interesting one. It’s a changing tradition, with more young adults and women getting into the sport who want to be connected to their food.”

Furman says that strong sense of connection with the land makes her optimistic that Vermont’s hunters and non-hunters can come together overcome these challenges. “We may not all agree about how, but we all want to enjoy our forests.”