Ted King’s Wildest Gravel Ride

What’s it like to ride 310 miles across Vermont in one day, on gnarly gravel?

By Ted King

A 310-mile ride will chew you up and spit you out. No matter how much I told myself to cool my jets, keep the powder dry, not go into the red, and any other metaphor with the message “Ted, don’t ride too hard too early,” I had a tough time doing so.

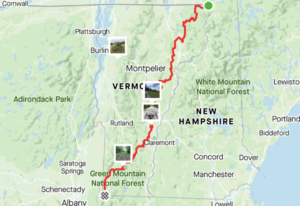

Let’s backtrack. It’s 11pm on Saturday night at the end of a dirt road in way, way northern Vermont. There’s a steady pelting rain as I make the checks to my gear, lights, computer, clothes. If I started trudging through the woods north of where the road ends, I’d meet the Canadian border in a matter of minutes.

Instead, I’m about to set off south to the Massachusetts border: 310 miles of pedaling are ahead of me, 90 percent of it is gravel, and the pre-ride mapping software tells me I’m in for 31,000 feet of climbing—but it will actually tally just shy of 35,000 feet. I’m as fresh and ready as ever.

Time to get #DIYgravel Dirty Kanza going!

Rain pools on my computer screen already bright with glare from my headlamp. I have a hard time taking the information in. Anytime I get a clear reading I’m pushing power just shy of threshold. It feels easy. Weird.

Is it calibrated? Yup. I guess I’m just itching to go. The climbing starts from the get-go and the road deteriorates from “tame gravel road” to “backwoods of rural Vermont” quickly. Really quickly.

I’m an early-to-bed, early-to-rise kind of guy, so setting out at 11pm is well past my bedtime. I took a nap Saturday afternoon, May 30 — Dirty Kanza Saturday. Those will be the final 90 minutes I’ll sleep for the next 23 hours. I’m so brimming with adrenaline (or coffee), though, that I’m also wide awake here in the early hours of Sunday. In any other context, namely if I were off my bike making my way through this heavily forested woods, I’d be spooked. The way my handlebar light shoots a cannon of light forward, bouncing off puddles and into the woods feels like an eerie black and white kaleidoscope miles from any civilization.

The first six hours are pure novelty. I’ve ridden at night, I’ve ridden in the woods, I’ve ridden in the rain, I’ve ridden in ferocious wind. Throw them all together, however, and this is unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. The rain increases as temperatures drop. At the top of every climb where the wind is the most intense, there are trees down sporadically across the rough gravel road. There’s so much climbing that my estimated 15mph is optimistic. It’s slow on the uphills for obvious reasons; I’m slow on the downhills because the roads are harrowing in the best of conditions, made all the worse with the weather.

The sun is still behind a wall of clouds at sunrise, but it lights up the world as I roll into Ian Boswell’s driveway somewhere around 6 am. He has hot coffee and Pastry Chef Boswell has even prepared sausage cheddar muffins. I take five minutes to warm the mind and soul. I feel like this first 100 miles of riding in the wet darkness are a closed chapter with nothing but sunshine and tailwinds ahead.

And then we start climbing.

Here I am 7 hours into the ride when I meet a freshfaced, fresh-legged Ian—a guy who has been racing the Tour de France for the past few seasons. I bite my tongue as we go up and down and up and down and up and down on ever deteriorating roads.

Mind you, this is not a complaint. This ride is breathtakingly beautiful. I’m just the nincompoop who decided to link the start and finish together in one fell swoop on a bikepacking route that was originally designed to be done over four to six days.

It’s somewhere around my tenth hour on the bike that Ian says, “Geeze Ted, this route is super hard!” I breathe the biggest sigh of relief of the day. It’s not just cumulative pain that has me deep down Struggle Street here in the heart of central Vermont.

This route is the brainchild of Joe Cruz, the bikepacking wizard from Pownal, Vt. I knew of his mapping prowess and penchant for an adventure when I reached out to ask if he’d ever connected the northern border of Vermont to its southern border on gravel. He hadn’t, but that sent him on a mission.

Joe is meticulous and doesn’t just study ridewithgps.com. He also searches public town records for the best public roads — ahem, “roads” — available. It’s no wonder his hobby is bikepacking, but his career is teaching philosophy at Williams College. I say goodbye to Ian, who’s in for a century of his own, at my mile marker 147. I’m not even half-way done. I take the advice that’s been barked into an earpiece in Pro Tour races throughout my career, “Eat and drink, eat and drink, eat and drink”. Over the next 30 miles I slowly come back to life. As I roll into Sharon, I know my wife Laura and baby Hazel are waiting for a quick hello.

The next hundred miles are a blur. No matter how much momentum I get going, I can’t break 15mph. The climbing is relentless. If the hills ever get shorter, that just means they’re steeper. The one definite standout of this section is that people are out. I’m broadcasting the route with a traceable Garmin inReach, so a few dozen people are in their front yards, at intersections. Some join me for a pedal down for a mile or five. If that doesn’t raise my spirits, nothing will.

The longest climb of the day is about 260 miles into the ride—a six-mile snowmobile trail. The path is rutted, doesn’t see much traffic, and is so bumpy that it’s pretty much suited for a full suspension mountain bike. That’s a take-home message for the day: this route is burly and were it not for the plush Cannondale Topstone Lefty, I don’t know how I would have gotten through this ride.

Certainly not in one day.

Up and over, down the final climb, a lightning fast six-mile descent, never has the final 10 percent of a ride felt so far. I’m well past my 8 pm estimated arrival. Thanks to the tracker, more and more people are out cheering me on. A few cars shuttle ahead of me. People pop out, cheer, hop in, shuttle ahead, pop out, cheer. I really can’t think of a time that company on a ride has been so welcomed. When I finally reach the border. there’s a big marble slab that denotes Massachusetts on one side and Vermont to the other. It’s now well past 10 pm and still a handful of people are there to cheer me in.

Superlatives are a strange thing when they’re subjective. Is it the longest ride I’ve done? Absolutely yes, by nearly 100 miles. Is it the hardest? The worst? The best? The coolest? The gnarliest?

All good questions.

I’ll tell you what, ParisRoubaix is hard. Dirty Kanza is hard. Vermont’s 200 on 100 is hard. #DIYgravelDK is definitely in the running for hardest.

This ride was, perhaps, the most legendary.

Read more about great gravel rides (that’ll be back next year!) you can start training for now.

This VT Sports Magazine chat is between Ian Boswell and Ted King and covers everything from riding as kids to King’s Rooted Vermont ride.