Stupid Pain, Plenty of Gain

Road Cyclists Climb the Northeast’s Peaks for the Bike Up Mountain Points Series

Road rider and hill-climbing specialist Charles McCarthy understands that racing all out, up hill, isn’t for everyone. He happens to be good at it, holding the course record up Appalachian Gap in the Allen Clark race, completing the grueling 6.2 miles in 24:27 last October.

Road rider and hill-climbing specialist Charles McCarthy understands that racing all out, up hill, isn’t for everyone. He happens to be good at it, holding the course record up Appalachian Gap in the Allen Clark race, completing the grueling 6.2 miles in 24:27 last October.

“I do get that question a lot: ‘You are paying to do this?’” says McCarthy.

McCarthy and 1,148 others did pay last season for the chance to enter a hill-climb race to pit themselves against each other and the momentum-killing pitches of some of the steepest stretches of pavement in the Northeast.

For the past two seasons, riders like McCarthy, who love to climb, have had a way to see how they stack up against fellow competitors in the Bicycle Up Mountains Points Series, which tracks results in a series of nine races and at the end of the season, crowns the Northeast hill climbing champion.

The longest race in the series is just 9.4 miles, but distance can be deceiving.

The vertical climb ranges from 1,600 for Appalachian Gap (6.2 miles) to 4,720 feet for Mount Washington (7.6 miles). Add up the total vertical for all nine races and you get 27,318 feet—that’s Mount McKinley with a Mount Washington stacked on top.

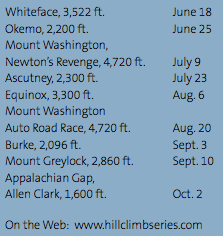

The races in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont and New York happen from June through October. They comprise some of the toughest climbs in the Northeast, including Mount Washington, Mount Equinox and Whiteface.

The races in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont and New York happen from June through October. They comprise some of the toughest climbs in the Northeast, including Mount Washington, Mount Equinox and Whiteface.

It might as well be Bicycle Up Mountain Pain Series. Cranking up stupidly steep grades hurts.

“You have to go into it knowing this is really going to hurt,” says McCarthy, 31, a school teacher from Lincoln, who last year, was the top Vermonter in the series (placing fourth overall). “There’s no comfort zone. There’s no reprieve or anything. You can stop when you cross the finish line. In a road race, there are plenty of times you can sit in the pack.”

The series was the idea of a builder and bicyclist from West Glover, Keone Maher. Maher was racing hill climbs and thought, Why not connect the dots—or climbs—and crown the Northeast hill climbing champion? Maher also started the Burke Mountain Bike Race hill climb, which is part of the series.

BUMPS got underway in 2009, and, with the exception of Mount Greylock, all of the races were in existence before the points series started. Hill climbs draw a mix of competitors, from McCarthy—a top amateur road and mountain bike racer—to riders in their 70s. The entrants skew older and male with 40 percent falling in the 40-to-50 age bracket, says Maher. There’s even one competitor who rides his bike to each event from his home in Amherst, Mass., and he’s in his 70s.

Riders are scored based on their best five results. Those who complete fewer than five races are not likely to score high in the series. The most difficult climbs are more heavily weighted in points. The first year, 940 riders scored points and last year 1,149 scored points, meaning they competed in at least one of the races. Last year, 77 riders completed four or more races, seven men and one woman earned Ironman honors for finishing every race in the series.

Marti Shea of Marblehead, Mass. has dominated the women’s field both years. She was the top woman in every climb she entered last year, including both Mount Washington races. (The series includes two Mount Washington races.) She set records on Ascutney and the Allen Clark. She also holds the record for Equinox and Greylock. While she only got on a road bike about five years ago, the strength and conditioning coach is not new to competition. Shea, 48, was a distance runner who earned a berth at the Olympic Trials and ran for Nike.

Marti Shea of Marblehead, Mass. has dominated the women’s field both years. She was the top woman in every climb she entered last year, including both Mount Washington races. (The series includes two Mount Washington races.) She set records on Ascutney and the Allen Clark. She also holds the record for Equinox and Greylock. While she only got on a road bike about five years ago, the strength and conditioning coach is not new to competition. Shea, 48, was a distance runner who earned a berth at the Olympic Trials and ran for Nike.

While pain is the common denominator, every climb is unique Shea says.

“Some come at you right away, like Mount Washington and Ascutney. Others are more gradual and you get into more of a rhythm,” Shea says. “All the climbs are so different you can’t prepare the same way. They all have different personalities and you can’t use the same strategies on all of them.”

Shea is quick to point out that the pain of each race isn’t what she remembers, which is probably why she and other racers keep competing in hill climbs.

For McCarthy, it’s the laid back, friendly (compared to elite road racing) competition that holds appeal.

“I’m not saying I’m going to the hill climbs to have a beer afterwards, but we’re having a picnic with a bunch of like-minded people who like to ride in the mountains. There’s just this one part that’s a lot of pain.”

Leslie Wright is a writer and rider based in Addison County.