Searching Wallface

Alex Stevens set out to camp on one of the Adirondack’s most remote peaks over Labor Day weekend. Two weeks later, Stowe Mountain Rescue joined the search party for him. Photos by John Wehse

If you Google ‘Wallface Mountain, NY’ the first site to come up is a climbing site, Mountain Project. The description is almost beckoning. It reads:

“Wallface is the largest and tallest cliff of New York State: almost 800 feet of very steep rock. With its quite long access from the end of the road and rather undefined access to the base of the cliff, Wallface definitely has an alpine dimension. Don’t be scared though, climbing this huge cliff is really very interesting and enjoyable!”

It may have been that description, or a similar one (or simply the mountain’s reputation in climbing circles), that enticed Alex Stevens to seek out this rocky buttress in the remote Western High Peaks Wilderness of the Adirondacks.

Stevens, a 28-year-old from Hopewell, N.J. was fascinated by Wallface—enough so that he drove alone to the Adirondacks for a Labor Day weekend camping trip. Though he had been climbing at his local gym and took trips to boulder and climb around the Northeast Kingdom’s Mt. Pisgah, Stevens hadn’t planned to climb Wallface. He carried no ropes or other climbing gear.

Friday, Sept. 1, was sunny with a high of 54 degrees in Lake Placid and overnight lows dipping to the 30s. On Saturday morning, Stevens parked at the Upper Works trailhead in Newcomb. He marked in the Indian Pass trailhead register that he planned to spend three days hiking and camping.

Stevens trekked the 6 or so miles to the base of the cliffs, accounts report, carrying a silver foam bedroll, a light green backpack, a hammock and tarp. He left his sleeping bag in the car.

At the base of Wallface’s towering cliffs, Stevens paused and spoke with two climbers. The New Jersey man, the climbers noted, was wearing a blue cotton t-shirt and open-toed sandals. His blond hair was tied in a bun. They were the last two to see him.

On Sunday, Sept. 10, at 1:45 p.m. the Department of Environmental Conservation Ray Brook Dispatch received a call from a family member saying that Stevens was missing after he failed to meet up with friends, as planned, in New York City.

That’s when the search started.

THE SEARCH BEGINS

The area around Wallface Mountain, though just 10 miles south of Lake Placid, is some of the most  remote and densely forested in the Adirondacks. Cell phones don’t work here. The few trails slash their way through the dense forests. “At times, you’re not even walking on dirt, just pine branches, and crawling over blowdowns,” says Doug Veliko, Chief of Stowe Mountain Rescue. In lower parts, the terrain is so boggy you can sink in mud to your thighs.

remote and densely forested in the Adirondacks. Cell phones don’t work here. The few trails slash their way through the dense forests. “At times, you’re not even walking on dirt, just pine branches, and crawling over blowdowns,” says Doug Veliko, Chief of Stowe Mountain Rescue. In lower parts, the terrain is so boggy you can sink in mud to your thighs.

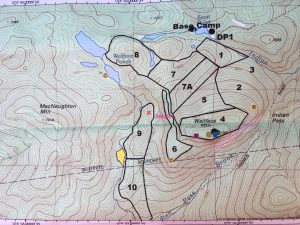

On Sunday afternoon, the day of the phone call, three local forest rangers set out and searched the trails on foot with two scouting from a helicopter above. By Monday, Sept. 11, more than 27 people from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), New York’s Homeland Security and state police force were involved in the search. Search and rescue and logistics personnel were called in from around the state, some driving from as far as Long Island to participate.

On Sept. 12, searchers discovered signs of a camp at the summit of Wallface and found some items belonging to Stevens, including two water bottles, earplugs and a strap from his hammock.

For a week, teams walked grids through the forest, searching the understory for any sign. By the end of the week, they still had not located Stevens. That’s when they called in Stowe Mountain Rescue.

“We often get calls from the Adirondacks because we know that type of terrain and have worked with the teams over there,” says Veliko, a rock climber and backcountry skier with extensive wilderness experience.

To even become a member of the elite 20-person search and rescue team, you have to come in with a strength in the outdoors, says Veliko who also holds a full-time job as an electrical engineer at Global Foundries, in Essex, Vt. “We look for people who are accomplished rock climbers, have done extensive hiking, mountain biking or backcountry skiing. We expect you to know the mountains and wilderness. Then we start teaching the rest.”

There is a rigorous exam, a six-month probationary period and weekly two-hour trainings. The team practices rescues high in the cliffs of Smuggler’s Notch and in lakes and rushing streams, in all seasons. As SMR’s website stipulates: “Our team includes personnel with Emergency Medical Responder training all the way to Advance Emergency Medical Technician qualifications. These skills may be deployed while on the edge of a cliff or in the middle of a flood.”

When Vermont created a state-wide Search and Rescue Coordinator position in 2012, it tapped Neil Van Dyke, a 37- year veteran and former Chief of Stowe Mountain Rescue to help coordinate search efforts among the various law enforcement and safety groups around the state. Van Dyke was also part of the team that headed to Wallface.

On Saturday, Sept. 16, Veliko and six other members of the rescue team headed to the Adirondacks for what was to be a three-day stint on the search. A camp had been set up on Scott Pond, below the mountain. The Stowe team was flown in by helicopter, the same that had begun the search a week earlier, using infrared cameras to scan the cliff face for a sign of human activity.

“Everything was supremely well organized,” says Veliko. “They had a logistics team in place that took care of food and supplies and a management team that was organizing the search. It was up to us to get out there and look for him.”

The teams had already gleaned a few clues. Stevens had bushwhacked his way up the cliff most likely following the remnants of an old climbers’ trail. He had set up camp at a tiny clearing on the summit on Saturday. He had run out of water. Two water bottles were found on the summit, one on the western slope. “The water bottles had signs of moss in them which may have meant he was trying to squeeze water out of the moss that grows on the rocks up there” says Veliko. There was no other water source near the exposed summit.

On the evening of Saturday, Sept. 2, temperatures dipped down below freezing in the town of Lake Placid. At the 3,727-foot summit of Wallface, where Stevens camped, they would have been much lower. On Sunday, Sept. 3, the weather turned bad. Rain started early in the morning and continued throughout the day. “We figured that at that point he broke camp and started down,” says Veliko. Stevens didn’t go down the way he came up. “He may have looked for a short cut or thought he could bushwhack his way to the base,” Veliko surmises.

On the evening of Saturday, Sept. 2, temperatures dipped down below freezing in the town of Lake Placid. At the 3,727-foot summit of Wallface, where Stevens camped, they would have been much lower. On Sunday, Sept. 3, the weather turned bad. Rain started early in the morning and continued throughout the day. “We figured that at that point he broke camp and started down,” says Veliko. Stevens didn’t go down the way he came up. “He may have looked for a short cut or thought he could bushwhack his way to the base,” Veliko surmises.

The Stowe Mountain Rescue team joined the grid of searchers on Sunday, September 17, covering Wallface’s northwest face. “When you do a grid, you walk in a straight line within eyesight and earshot of another searcher,” says Veliko. Normally that might be 15 or 20 feet away. “Here, the trees were so tight and dense that we were five feet away from each other and couldn’t see each other. Tree trunks were sometimes inches apart.” The dense krummholz and spruce and balsam scrub were nearly impassable in places. There were no trails. Blowdowns and boulders often blocked the teams’ progress.

SURVIVING IN THE WILD

At 11 a.m. on Monday, Sept. 18, another search team found Alex Stevens. His body lay in a scree field, in the bottom of a drainage near Wallface Pond. He was on the opposite side of the mountain from the trail he had come up and, as the crow flies, a half mile west from his campsite on the summit. There was no sign of an injury. The coroners’ report stated he had died three days earlier of pneumonia, what was termed an “easy diagnosis” based on the build-up of mucus in his lungs.

Wallace had been wandering that stretch of forest for more than two weeks before he succumbed. Had he made it to Wallface Pond, he might have found a side trail that leads from Wallface and Scott Ponds two miles back to Indian Pass Trail, the trail he set out on on Sept. 2.

“When you are in forest this dense, it’s easy to walk in circles,” says Veliko, adding: “Stevens had run out of water and food, we know that, and was probably already dehydrated and disoriented.”

“You can survive for a month in the wild with no food,” Veliko continued, “but the longest you can go  without water is about three days. Your body starts to break down and becomes more susceptible to sickness.”

without water is about three days. Your body starts to break down and becomes more susceptible to sickness.”

As the Essex County Coroner Francis Whitelaw, who examined Stevens body, said: “Your brain lives on carbohydrates for the most part, and if you don’t get carbohydrates over a long period of time it’ll really play with your mind, and you are going to make bad decisions, and just not going to be able to function after a while.”

Among the other things that searchers noted: there was no sign that Stevens carried any thermal clothing. He was wearing a cotton shirt and hiking boots when his body was found. He had a cell phone (though there is no service in the area). He had no compass or re-starting materials.

“Whenever I hike, I carry a small daypack that has six or seven Powerbars, a space blanket, compass, a restarter and first aid,” says Veliko. “Even the most experienced hiker should never set out in an area, particularly in the Adirondacks, that you don’t know alone. If Stevens had been with someone or even told someone where he was going, we might have found him when he was still alive. Any time you set out without a means of communication and alone, you’re opening yourself up to risk.”

For Veliko and other members of Stowe Mountain Rescue who handle up to 40 rescues a year it was one of their few searches that did not end in a rescue.

For the Adirondack teams, it was one of many. In 2016, there were an unprecedented 350 backcountry searches in the region. “It’s wild terrain out there,” says Veliko. “People need to go out prepared.”