Preseason tune-up – Getting your skis ready for the season with a pro

By Evan Johnson

The guns are on, the temperatures are dropping and across the Northeast, skiers and riders are pulling out their gear and getting ready for opening day or at least the first big Nor’easter. While waiting, it’s important to make sure your equipment — backcountry or alpine, skis or snowboards — is ready.

Edges need to be removed of rust and that rock you went over in April may have really done a number to the bottoms of your skis or board. You can do much of the tuning on your own, or, fortunately, there are pros to help. We spoke with Dave Rowles, a technician at Alpine Options near the base of Sugarbush, to get some tips. Rowles knows skis. He’s been tuning them since before he knew how to ride them. His brother gave him a tuning kit for Christmas when he was 14 and he got a job at a local ski shop two years later. He walked us through the basics of tuning skis for the midseason, including:

- Removing burrs

- Beveling edges

- Base grinding, if needed (to flatten your ski)

- Stone grinding, if needed (to add structure)

- Waxing

Removing burrs and beveling edges

Burrs result when a finely tuned edge on your ski or board gets dinged or worn, resulting in small filaments and protruding edges. The first step in tuning is to remove these with a diamond stone and then with a fine ceramic stone. Rowles advises wetting the tools first to make them last longer.

New skis come with factory edges and will hold and perform while the skis are new. But with wear and tear, edges inevitably wear down. For carving turns, edges must be sharp along the entire length that makes contact with the snow. Therefore, having them re-beveled and sharpened at the beginning of the season can boost the performance and life of a ski’s or board’s edges.

Base edge beveling lifts the edges off the snow a slight amount (.5° – 1.0°) so they will only engage until the ski is lifted onto an edge. This can be done at the workbench at home using a file and a guide. Guides come in a variety of grades ranging from the cheap plastic kind to the ultra-professional, but Rowles says the key is to bevel the base edge correctly the first time.

“A hard thing for most people to understand is the base edge. Once you’ve set the bevel at one degree, you can’t change that unless you re-flatten the whole ski. It’s trying to cut a two by four at six feet and then trying to go back and cut it at six and a half. You can’t do it.”

Now that the bevel is set and the angle is sharp, it’s important to remember to detune a portion of the edge. If the edges remain as sharp and defined as you (or the machine) made them, it will be difficult to either initiate or come out of a turn. That’s because the sharpness in the tip and the tail works to continue your skis in the direction of travel. After dulling the edges using a file, de-burr the dulled edges with a diamondstone or ceramic stone.

Base repair, grinding, stone grinding

The bottoms or bases of the skis see an occasional rock, stump, or patch of dirt. To keep the ski gliding smoothly, the nicks or scrapes on the bottom need to be filled-in using a material called PTex, a malleable synthetic material that melts when heated. Your ski shop feeds it into a hot glue-gun type of device that runs for around $100, but it melts easily at home with a lighter. Drip into the scratch or gouge and let it dry, then scrape to smooth it off.

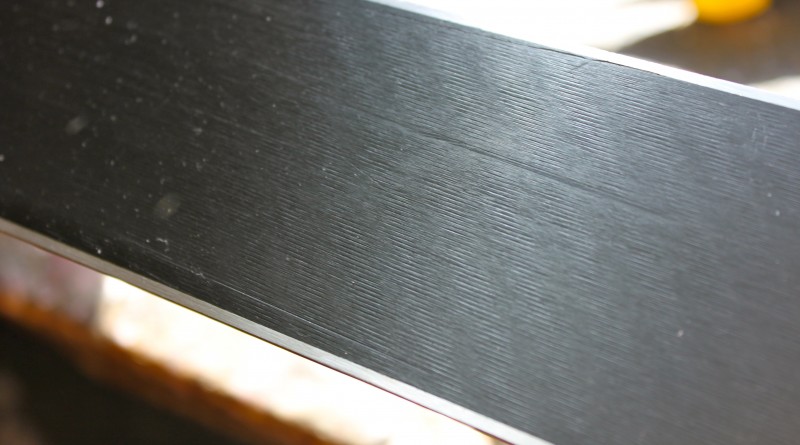

If the damage to the bases is serious enough, you’ll have to have the bases grinded. In years past, Rowles said, a few people used to flatten the bases of their skis using belt grinders, but that’s risky business on an expensive ski or board. Most ski shops will have a machine for the task to do the job, and it’s worth the cost. The stone grind will restore the base to a smooth finish to reduce drag.

Depending on snow conditions and your style of skiing, stone grinding belts can apply a number of finishes to the bases of skies, but leave the obsessing about the merits of arrow versus linear patterns to the world-class skiers. A good base grinding at the beginning of the season will make your skis move faster through the snow, you’ll ski or ride better, and you’ll have a lot more fun.

Waxing

For home tuning, Rowles says, there are basically two kinds of wax: red and blue.

Like bases, this is another area of ski maintenance and tuning that’s easy to get bogged down in the minutiae. Back when all ski bases were made of wood, waxing was only necessary to make the ski slide down the hill.

While the polyethylene bases of today are more durable and produce less friction, repeated waxing is still important throughout the season. Waxes come in a variety of types for Alpine and Nordic skiing and suit a variety of temperatures.

Wax works to overcome different kinds of friction with the snow by acting as a lubricant under your ski and protecting the bases from forces that contribute to oxidization. A properly waxed base is easier to turn, more durable and faster than going waxless.

Rowles says any skier should know how to wax their skis and should do so along with checking their edges every week.

Drip the wax on with the iron, then scrape off with a plastic scraper while the wax is still molten or warm. Repeat until you don’t see any dirt or discoloration in the wax scrapings – this means the base is now clean. Then clean off the bases with a brush.

New skis, new tuning

Tuning is hardly a one-size-fits-all operation. As skis develop and change every season, so do the techniques of tuning them. Newer and wider skis designed for powder have a more rockered shape than traditional models, meaning a difference in where the tuner detunes the edges. While with traditional models, it is normal to de-tune one to two inches from the tip to the tails, with fatter skis you can expect to detune four to six inches from both ends.

Binding test

A final, crucial step in preparing skis for the season is to test the bindings, a task best left to the professionals, who use a binding torque release testing machine. The machine exerts enough torque on the boot to cause it to eject from the bindings, simulating a crash or any event when the boot becomes forcefully ejected.

Because bindings are mechanical devices that deteriorate with wear and use, the test will ensure that the reading on the DIN release scale is in fact the value at which the bindings will release.