Northern Forest Canoe Trail: Two Ways to Travel

By ZACH DESPART AND PHYL NEWBECK

ADDISON — In May 2013, Peter Macfarlane found himself in a bit of trouble.

He’d been canoeing across Lake Champlain and up the Missisquoi River for seven hours, enduring pouring rain and sustained wind of 25 miles per hour.

“The conditions were foul, and things were looking bleak,” MacFarlane recounted.

Then things got bleaker. Trying to sponge rainwater out of the vessel, Macfarlane put too much weight on his seat. It cracked in half, forcing him to kneel while paddling.

He thought an improvised solution would be to sit on an exercise ball, if he could find one the next time he stopped. Then, miraculously, he found a beach ball, emblazoned in Disney characters, floating in an eddy near the Route 78 bridge in the Missisqoui National Wildlife Refuge. MacFarlane scooped it up and used it as a makeshift seat.

“So, as it were, I sat astride Tinkerbell,” Macfarlane recounted. “That was my seat all the way to Swanton.”

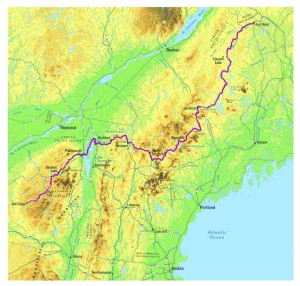

This is just one of the obstacles Macfarlane encountered during his 28-day trek of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, a 740-mile trail from northern New York to Maine. Of that distance, adventurers spend 50 miles carrying their canoes and packs between bodies of water. Just a few more than 70 paddlers have claimed to have paddled the trail since it was completed in 2006.

Macfarlane, 51, looks like a guy who would attempt to paddle 740 miles on one canoe trip. He’s lanky but muscular, and his pale blue eyes contrast with his tanned, weathered face.

A native of England, Macfarlane in 2003 emigrated to the United States to be with his wife, Viveka Fox, after they had “done the trans-Atlantic thing a mere nine years.” The couple lives in Addison, and Macfarlane owns a custom boat-making business called Otter Creek Smallcraft.

Through his youth and adult life, Macfarlane said he has always participated in outdoor sports, including canoeing, hiking and bicycling. He completed a number of kayak marathons (events he said are best described as “flatwater races over a ridiculously long distance”) working his way up to a 125-mile race in southern England.

He decided to attempt the Northern Forest Canoe Trail in part to celebrate his 50th birthday. Macfarlane, who retains his English accent and its impeccable diction, spoke excitedly about his trip.

As a former kayak racer, his previous canoe camping experience had been limited to 15-mile days for a week at a time, but on this trip he averaged 28 miles a day with one 40-mile day.

“The challenge is no small part of it,” he said. “Being able to travel from A to B under my own steam and pitting my wits against something bigger than myself with no guaranteed outcome made it an adventure.”

Macfarlane took 28 days (27 paddling and 1 “rest” day during which his support crew brought him to Lancaster, N.H. for a musical gig) to complete the trail in the spring of 2013. He went with a lightweight boat of his own creation; a 37-pound, 14-foot cedar-strip solo canoe.

In addition to one short and one long paddle, he brought two ski poles to double-pole in shallow water. Macfarlane carried 48.5 pounds in his pack to last half the distance, replenishing his food supply at the midway point when he rendezvoused (and fiddled) with his support team. He was able to single-carry each portage rather than carry his gear and then return for his canoe; important since several portages are over five miles long.

“It’s a canoe trip and the carries are a necessary evil,” he said. “Anything I could do to minimize the discomfort in carrying, I did.”

The biggest problem for Macfarlane was that both May and June of 2013 were the wettest on record for Vermont and he frequently had to battle strong currents when going upstream. In a bit of cruel irony, before the trip Macfarlane had urged his friends to pray for rain, since an unusually dry April and May had left river levels below normal.

His boat survived with minimal injury aside from two interior breaks in the fiberglass that were repaired with duct tape, and broken seat rails that required a stop at a hardware store.

Rather than deal with the weight of a tent, Macfarlane brought a hammock and tarp. For cooking he used a collapsible wood stove, which, due to the wet weather, was occasionally unable to function. At the halfway point he reluctantly added a gas stove and cylinder.

Only three of his paddling days were completely rain-free and the almost-constant precipitation forced Macfarlane to supplement his camping with five nights in private houses, four nights in motels and inns, and three nights in picnic shelters.

In one instance, Macfarlane, sopping wet after another day in relentless rain, trudged into the Abbey Restaurant in Enosburg Falls, Vt. While warming himself with a cup of hot chocolate, Macfarlane struck up a conversation with a couple at a neighboring table who happened to be celebrating their 30th anniversary. The couple offered to help Macfarlane find shelter for the night.

“They invited to take me to a motel,” Macfarlane said. “Then they actually withdrew that offer because they came up with a better one — they took me home with them.”

The couple, who Macfarlane called “trail angels,” dried his clothes, offered him a bed to sleep in, fed him breakfast in the morning and brought him back to the river. Macfarlane said he feels obligated to repay the kind strangers by helping out a traveler as they did.

“Oh yes, I’ll have to pass it forward,” he said.

But his difficulties weren’t over, as the rain continued day after day. Even with the almost constant deluge, Macfarlane said he never felt like quitting.

“My lowest point was on Allagash Lake on Day 24,” he said. “The forecast said a 30 percent chance of showers after 1 p.m., but it started raining at 7 a.m. and got heavier and heavier.”

Macfarlane became hypothermic for the second time on the trip.

“I was beginning to lose coordination, which is one of the early signs of hypothermia,” he said. “Just being cold is bad enough, but losing coordination is an indicator that you have to do something about it very quickly.”

“It was then my motivation hit rock bottom,” he said.

The next morning it took him over an hour to get out of his sleeping bag and back on the trail, even though he knew he was near the end. Four days later he would complete the journey in northern Maine.

Despite his soggy experience, Macfarlane enjoyed his time so much that he has signed up to maintain the first segment of the trail in Vermont.

**********

Compared to Macfarlane, Sam Brakeley and his friend Andy Rougeot, paddled the trail in a style more similar to the QE2. In 2009, the two college students decided to go “old school,” heading out in a 50-pound Old Town Penobscot (canoe) carrying wanningans (wooden boxes with leather straps), an axe, saw, individual tents, and waterproof duffle bags for a combined weight of roughly 220 pounds, which meant that their portages almost always required two trips.

They restocked their food supply fairly often with the last six days on the trail being the longest without a food stop and spent four nights indoors, two of which were bracketed around their sole rest day.

The high point of the 39-day trip for Brakeley was Spencer Stream and Attean Pond in Maine.

“It was some of the prettiest paddling and at that point we were really in a groove,” he said.

A less enjoyable day was on the South Branch of the Dead River in Maine after a torrential downpour turned the normally twisty river into a straight line or turbulent water. The boat flipped rounding a corner and it took over a quarter of a mile for the canoeists to right themselves. They were able to exit the river and spent the rest of the afternoon figuring out what needed repairs and what had been lost. They stayed in a hostel that night and hitchhiked to a store the next morning to get a new tarp and tent among other supplies. Hitchhiking back to their canoe, they lost roughly a day of paddling time.

Brakeley was an experienced long-distance paddler, having paddled as a youngster and guided month-long trips for his old summer camp, as well as doing some solo long distance canoeing.

“My through paddle was the start of a long involvement with the Northern Forest Canoe Trail,” said Brakele, who enjoyed his trek so much that he wrote a book about his experience. “The following year I worked on a trail crew and I continue to work part time for them.”

**********

Of the various ways to tackle the 740-mile canoe trail, or any long-distance portion of it, Macfarlane has one piece of advice.

“Prepare,” he said. “Do a few overnight trips and see how it works before embarking on something that might end up miserable. Prepare for nearly all eventualities or as many as possible.”

For now, Macfarlane has no adventures on the horizon, but he said he always keeps an eye out for new challenges. This summer, he and Viveka have spent as much time as they can on canoe trips.

“We often go to the Adirondacks, but not always,” Macfarlane said. “We just go off for a few days at a time, canoe camping, getting away from it all. That’s sort of what floats.”

NFCT facts:

740 miles (160 upstream)

4 states

1 province

22 streams and rivers

58 lakes and ponds

63 portages (53 miles)

2000 – Northern Forest Canoe Trail organization incorporated

2006 – Northern Forest Canoe Trail completed