My Turn

When returning to the lake means the beginning of everything that comes next. By Jill Hindle Kiedaisch

Maybe it’s because I’ve been awake for three hours already, slowly moving on the mat, noticing what’s stiff, what’s open, trying to notice the change of light in the sky but not managing to catch it in the act, listening to another bird add her secrets to the rest of the sounds, thinking about my mom and how she wakes alone, and my dad, who never had to, at least not since their wedding day. Maybe that’s what lights my mind on fire, what pushes the adrenaline through my heart and out into my limbs before dawn.

I brew coffee and hug my boys as they each descend the stairs, hair spoking out like unkempt feathers, their soft, beautiful eyes still opening and adjusting to light as I ask them what books they want me to pack for the weekend.

Later, we will drive to a place by a lake where I’ve retreated since I was 17, where I would crawl stroke and side stroke between docks until breathless, stay in a suit all day, turn brown, sit alone on the peeling wood planks of the dock to watch the sun dip down behind the layered hills, wondering about the life that lay ahead of me – the life I’m in now that takes me back there to open everything up, let in the air, hook up the oat, hang the hammocks, rake the beach.

We will work first so we can rest later, so we can watch for herons and water snakes, for beavers at sunrise, their black noses splicing the glassy surface before the boat motors cough to life and whine across the bay—their sounds somehow a commentary on the people who own them. Our inboard makes a low, halting grumble these days, but I remember its assertive purr the day Dad first piloted it into the cove.

He called it My Turn as a joke, but also as a hard-earned sign that he was ready to retire and enjoy his financial independence from three kids, three college tuitions. He never went to the trouble of having the name painted on the stern, but someone gave him a hat with “My Turn” embroidered in yellow, and he wore it proudly whenever he toured guests around the lake, his turns—wide and easy around the markers—very much his own. That hat still hangs on a peg at the end of the hall next to the extra sweatshirts, musty fleeces and rain gear, because the evenings get cool and storms have a way of blowing in.

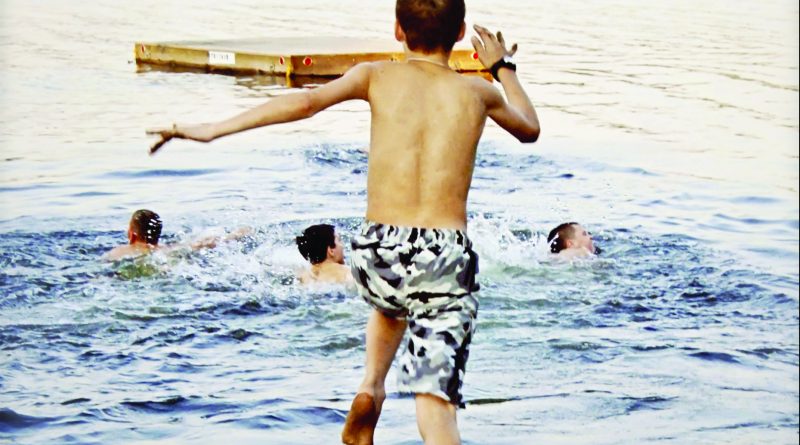

The lake arcs around our point to just shy of 180 degrees. You never forget you’re surrounded by water the way you can on the big islands. It’s the center of everything here – or rather, we’re the center of it. We stare at the water constantly, reading it like a weather map, a star chart, like a clock. When the wind’s up, we sail, canoe when it’s not, haul out the kayaks when the wavelets slide gently up the sand. Phones lay untouched on bedside tables as we dust off board games, string up the badminton net, deal out hand after hand in the shade of the screened porch, remarking on loon calls even though we’ve heard them a thousand times.

This spring, the neighbors called with news that the docks are in rough shape, that Dad’s flagpole – the one he dragged from the center of the island, limbed and stripped by hand, then installed at the end of the mail dock — has toppled and is underwater now along with the spotlight timed to switch on at dusk right around cocktail hour.

For years, we used that flagpole as a guide when coming across the water. But this past winter, our first without Dad, the lake never froze solid the way it used to. It froze some, then thawed, then froze some more, and the prevailing winds pushing in from the north sent ice floes straight into our dock piers, leaving them lurching like fun-house ramps, half in, half out of the water.

So there’s work to be done and money to be spent and neighborly advice about repairs mixed in with inquiries after Mom and how she’s doing in the wake of losing Dad. I will fend them off with She’s okay, thank you. What do you say? What can you say when so much has changed?

But many things, when we get there, will be the same – like the view from the deck, which hasn’t changed in 25 years, and our crescent of sand where all eight grandkids learned to swim framed by the same worn rocks and overgrown blueberries and the tupelo that will turn red long before anyone is ready for fall. The hammock trees will still frame the mainland a mile away, and the birches will bend and rustle over the boat slip, casting just enough shade to see down into the shallows where the bluegills and the pumpkinseeds swim.

But for all the same things, this year feels different. It’s the beginning of everything that comes next. It’s the year we’ll decide whether to hang onto the place, though I’m not sure we can. With Dad gone, it feels like we’re already letting it go.

While packing, I worry it’s already too late. I need to assume this summer’s the last and soak it up more, hold it in longer. I decide I’m going to wake for every sunrise and putt out to the broad lake every evening at sunset. I’m going to teach another niece or nephew to waterski, doing my best to drive like Dad drove.

My mother instructed me to steadily slide my toe into the invisible boot behind me after dropping one, left leg burning, right toe searching and not finding the boot, eyes on Mom in the back of the boat, her arms straight, reminding me to do the same until I was up and out of the water. I’d ski like that, too, zombie-armed, pointed toe trailing wildly in the wake, thinking, shift weight slightly, slide foot in, lean back nice and easy. Letting the right leg finally take the weight, I’d do a lap (hardly ever two) then pat my head for home, Mom’s smile shooting back at me across the water, the smile of a wild girl who used to slalom one-legged, her free leg flying out behind her like a dancer.

After the four-hour drive, we arrive. We load up My Turn, pile in, and pull away from the marina. As I push down the throttle, I notice my knuckles whitening around the wheel. When did this become less fun? When did I start worrying? There was a time when this place still felt like a dream, back when dreams were a regular thing for me, when I was 17, when the sensation of tumbling through the water with no sense of up or down frightened me less.

It’s okay, Mom would say as she leaned over the stern. You’re down, the worst is over, just let the water move you, and I’d grit my teeth, refusing to cry as I struggled to get the ski back on. Relax, came her voice over the widening gap between us as Dad shifted into gear. The more you let go, the less you’ll get hurt. And there, in those strange and lonely floating moments before the rush of sensation, I would watch the tow rope give up its slack, feel the tug of the engine at the other end, my right leg free and probing the dark water, my mind losing itself in the depths, in the faint whiff of gas fumes, the idle almost like cicada song, and there…a loon at eye level not 30 strokes away.

Arms straight, legs ready, I lift my chin and shout, “Go!”

Jill Hindle Kiedaisch is a columnist and editor for Parent.co and author of adventure fantasy novels for kids. Her work has appeared in nature anthologies and conservation magazines. She lives in Hinesburg with her husband, two sons, and two fish.