Vermont’s New Trail Hub

How a new generation of skiers and mountain bikers and trail lovers, (working with the town’s landowners and businesses), Is reinventing Randolph as an outdoor sports recreation hub.

It’s 11 a.m. on a Thursday in February and a group of nearly 20 teenage boys is roaming the streets of downtown Randolph, Vermont.

They move en masse toward an old building that has a 3D sculpture of a skier on one side.

They swing open the door of The Trail Hub. Inside, to one side of the rehabbed 1850s post-and-beam building is a bike stand where Robin Crandall and Robbie Leeson are at work, getting ready to open their new bike shop, The Gear House, on March 1.

On the other side of the building, Zac Freeman, a co-founder of the Rochester/Randolph Area Sports Trails Alliance (RASTA) is making stamped copper name plates for the area’s trail networks and putting the finishing touches on a 3D relief map of the Randolph/Braintree area—a broad expanse of enticingly green mountains with roads and trails criss-crossing it.

Freeman, 42, bounds through the room with a boyish energy pointing out the work he’s either done himself or worked with others to do. The son of two jewelers from Braintree, Freeman himself is a jeweler, woodworker and trail builder. But as RASTA’s Trails and Recreation Economic Director (TRED), he is now focusing on community development, and enhancing outdoor recreation resources.

On the wall is another relief map—this one of the entire state of Vermont. The Catamount Trail and Long Trail bisect it. Other parts of the map have yet to be filled in. On the other walls are framed topo maps showing sections of local trails that RASTA built and maintains. The now-legendary ski glades of Brandon Gap are there, and the new backcountry haven, Chittenden Brook Hut. That map will show the Braintree ski glades and bike trails.

Soon there will be more maps, including a new one that will chart some of the Randolph area’s best gravel/adventure rides, including 18- to 50-mile segments that make up Freeman’s own event, the Braintree 357, a fall gravel enduro race that offers up to 8,000 feet of climbing.

“Maps are what make the difference in where people choose to go. Everyone wants to find trails they can use legally these days,” says Paul Rea, when I talk with him later by phone. “And a bike shop, that’s where you go to get dialed into an area,” he adds.

Ground Zero

Rea, 51, is the former bike shop owner turned real estate broker and developer who owns this building. It was over a coffee at the downtown market with Zac Freeman that the two hatched the plan to rehab the dilapidated building at the entrance to town into a bike shop/trail hub. Rea footed the bill and provided a three-year lease; Freeman provided the vision, the grant-writing and the manpower.

The Trail Hub is the embodiment of all that people like Rea and Freeman, Angus McCusker

(the other founding partner in RASTA), and many trail building volunteers have accomplished in the small villages of Central Vermont and the Green Mountain National Forest the last few years: a club house/meeting place/resource center/bike shop, in a word, a trail hub.

“This is going to be Ground Zero for all our trail efforts,” says Zac Freeman as the teenage boys huddle around the 3D map. He traces various roads and routes. “Here’s where we snowshoed up for dinner last night,” he says pointing to a route up Braintree Hill. The boys trace other areas of the map, noting places where they might have mountain biked or hiked.

Out in the shop, a few are chatting up Crandall and Leeson, the 20-something managers, both avid mountain bike racers, ready to open the first bike shop Randolph has seen in decades.

The teenagers—all students at the Brunswick School, a private boys day school in tony Greenwich, Connecticut—have had a small hand in creating this space as well.

In 2017, Jesse “Sam” Sammis, a Brunswick alumn, sold his Three Stallion Inn and the surrounding 650 acres with more than 35 kilometers of trails to the Brunswick School for $2.14 million.

Since then, the school has made visits to the Randolph farm part of the curriculum. Groups of 20 students take the train directly to Randolph from Greenwich. When they arrive, they put away their cellphones and computers for a week. Their Vermont “curriculum” includes doing pro-bono work around the town.

“You should see all the weeds and debris these guys pulled off this building,” says Freeman. “The original site was worse than a mess.” In exchange, Freeman has contributed to the adventure portions of their visits, taking them snowshoeing or mountain biking and leading trail work days.

Brunswick seniors Eric Meindl and Maron Salame are in Randolph for the second time. As Meindl says, “The community has really welcomed us. We helped hang sheetrock at the new community center yesterday getting it ready for its opening in the next couple of months. It’s great to be part of growing Randolph.”

Salame adds, “The natural landscape here is something that we don’t have in Connecticut. When we come up here we really learn about leadership in the activities we do, like mountain biking or ice climbing. Last night,’ he adds, “we did a snowshoe hike up Twin Peaks and had chili dinner we brought, then ran down on snowshoes —it was like running on a cloud.”

Building on a Legacy

Some of the other land that Sam Sammis owned—land closer to Exit 4 off Interstate 89 that he had hoped to develop into a hotel—was purchased by a conservation group and now serves as a home to Ayers Brook Goat Dairy, operated by Miles Hooper and his partner. Miles Hooper, his brother Sam and other brother Jay (the Democratic representative of Orange County) are sons of Allison and Don Hooper. Allison, with business partner Bob Reese, founded Vermont Creamery and is now helping her sons carrying on local traditions.

The milk from Miles’ goats is used by Vermont Creamery and Fat Toad Caramel, the meat is sold by Vermont Chevon (owned by Miles) and is cured by Vermont Salumi, in Barre, and the leather goes to making Vermont Gloves, a century-year-old Randolph company Sam purchased in 2017. “We call this area Goat Town—we’re trying to use every part of the goat.”

An avid skier and mountain biker, Sam Hooper has also been part of the Randolph outdoor recreation revolution, participating in events such as the Braintree 357 gravel ride and to build trails. A good metaphor for what is happening to the town is what he is doing with the gloves that were traditionally used by linemen.

“We’re designing a backcountry ski glove with a woolen inner and using the goatskin gloves as the outer.” There’s also a gravel glove in the works.

“There’s a lot going on in this town now,” says Hooper. “We have Vermont Tech, we have a hospital, we have a golf course and we have a hotel planned for the land right next to Vermont Tech, near Interstate 89. That’s a big one because in the past few years there’s really been no place for folks to stay.”

There is also a new tubing hill and, possibly soon, a rope tow. In the 1950s, Harold Farr put up a rope tow on his farm near Elm Street so local kids could ski and toboggan for free. After many bustling winters, the rope tow and area shut down in 1966 when another ski area, Pinnacle, opened nearby.

Recently, local businessman Perry Armstrong and his wife Lynn purchased the 12-acre property, reinstated a tubing hill and are considering adding a rope tow. Last fall, a corn maze was cut on the property and on Feb. 15, 2020, Winterfest happened.

Half the town turned out to either volunteer or participate in Winterfest’s tubing, snow sculptures, igloo playground and box sled races.

The Once (and Future?) Festival

In many ways, the recent revival of Randolph as an outdoor center feels like history repeating itself.

In 1996 Randolph resident Sam Sammis welcomed a group of mountain bikers to his land and trails at Three Stallion Inn and the Green Mountain Stock Farm. Perry Armstrong, owner of Rain or Shine Tent and Events, supplied tents and Paul Rea, at the time the owner of Randolph’s local bike shop, Slab City Cycles, helped orchestrate what would be the first large mountain bike festival in the East: Pedro’s Mountain Bike Festival.

“I was working for Pedro’s at the time,” recalls Reese Brown, one of the festival’s first organizers, referring to the company that makes bike tools, lubes and accessories. “We wanted to do an event, something big. Paul Rea was great and Perry Armstrong, with his tent company, seemed to be able to make anything happen—heck, we even had a hot shower truck.”

Rea, who had lived out west, knew of the Crested Butte Mountain Bike Festival. “The idea was to have a festival like that here but without the competitive vibe—it was just going to be some great riding on this cool network of trails, good food and good music.”

For several years, it was all that –drawing as many as 2,500 to the town each summer with everyone camping. Rea’s bike shop boomed, trails blossomed and it seemed as if Randolph might have gone the way of Kingdom Trails.

But things fizzled. The event outgrew Sammis’ property so Rea moved it to land he owned. Then, as he said, “I needed to find a real job,” and he sold the shop. Brown left Pedro’s (he has since moved to Woodstock, Vt.) and the festival died. Rea passed on some of the wisdom he gained from the event to his old college friend, Jeff Hale (they had gone to Lyndon State College together) who, in 2000, became the executive director of Kingdom Trails.

Would Randolph ever hold the festival again? “We’d love to,” says Rea. “We’re in talks but the challenge is finding places for people to stay.”

Freeman, who was in high school at the time the Pedro’s festival started, is more cautious.

“Everything I’m trying to do and RASTA is trying to do is to not change the character of the town. We’d get a lot of pushback if we got too big. I’ve already had to deal with landowner issues, and am very focused on building this slowly for long-term sustainability.”

For now, Freeman is focused on building new trails around Randolph and on the Vermont Tech property. In March, 2019, Randolph and RASTA received one of the first Vermont Outdoor Recreation Economic Collaborative grants, $65,000 to go toward the Trail Hub, as well as building trails.

“We want to get a seasonal food truck in back of the building, a bar and maybe a shower and have bands here in the summer,” he says. “And then for winter, we’d love to get a trailer full of backcountry ski gear and take it around to local schools and help other kids learn how to backcountry ski.”

His eyes light up as he talks, living the dream that brought him back to Randolph where he was born and raised. He now lives in a house he built himself at the top of Braintree Hill, with his wife Shannon and son Ashar, 4—who is now riding many of the local trails.

“This truly is my backyard and playground,” Freeman says.

And he’s willing to share.

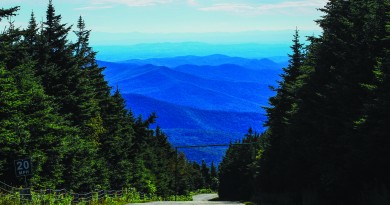

Featured Photo: Freeman shows Brunswick school students some of the local trails. Photo by Ben DeFlorio

Note: this is an updated version with several corrections. Vermont Glove is not working with Darn Tough but making its own woolen inners for its gloves. Ric Cabot, owner of Cabot Hosiery which makes Darn Tough, serves on Vermont Glove’s board. Additionally, Sam Hooper is a participant, not a sponsor, in the Braintree 357.