Trail Ethics and Entitlement

It is late fall, and I am seeing the hunters again. They park their pickup trucks at the trailhead near my house before dawn and vanish silently into the state forest. Late in the afternoon, I see them return. I often stop to talk with them about the hunt, the drought and warming weather and the changes to the forest. The hunters are good stewards of the land. I don’t post my property. They leave no trace.

A few years ago, our conversation shifted to something new. “Seen that new trail up there?” one hunter I knew asked as we chatted by the side of the road. I had an idea of the trail he was referring to. I had seen the builders, a posse of young backcountry skiers and mountain bikers, unloading gear at the trailhead. I hadn’t imagined they would do much to the land.

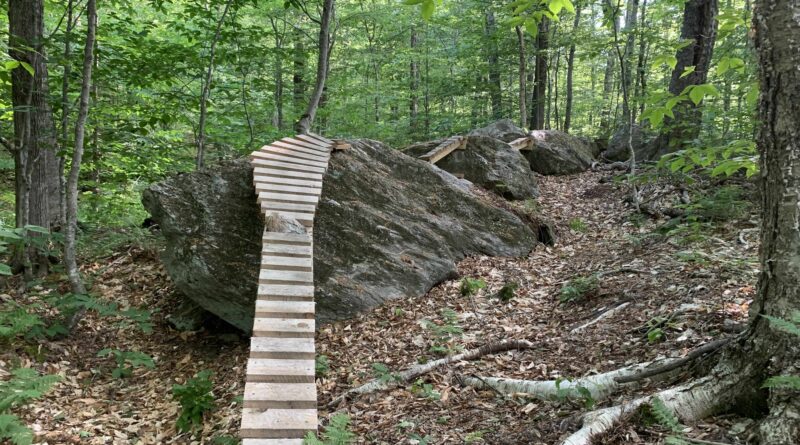

But when I hiked up what I saw was not a rake-and-ride mountain bike trail or just a gladed section of steep woods. More than 23 bridges had been built using pressure treated wood and bolted into rocks. Berms had been created and trees felled. Culverts were blocked with stones. Wooden trail signs were nailed to trees. I called the state forester. That forester reported he couldn’t find the trail.

It was another hunter who later alerted the local mountain bike club where, as it turned out, one of the rogue trail builders was an executive board member. The trail was dismantled. The state put up a metal sign indicating this was an “unsanctioned” trail. Despite a call for his resignation, one of the rogue builders remained on the board for another six months. Another complicit in that trail worked for VMBA and now leads a VMBA chapter.

I’d like to think this was an isolated incident and the people involved have learned from it. There is no point in naming their names or trail locations.

But that incident is far from isolated. The president of a mountain club in another part of the state was discovered building illegal trails in a town forest. When his board found out about it, they quickly asked him to resign.

In 2021, the Vermont Mountain Bike Association put out a position paper on the topic of rogue trail building. “Mountain biking in Vermont has a rich history. Trail building, use, and ongoing maintenance began long before VMBA was founded. Some of our most popular trails were built on public land without permission and were, eventually, adopted as official trails. This “ask forgiveness, not permission” approach is no longer serving our community and not only harms the relationships we have developed with public land managers but cuts the public out of the decision-making process of how our public lands should be used. Beyond trail building, riding on trails not designated for mountain biking on public land is in violation of State and Federal policy and further encourages and promotes rogue building.”

But things haven’t changed. In September 2023, the Upper Valley Mountain Bike Association issued a press release asking people to stop building rogue trails. “If you have seen someone working on the trail, please report it to UVMBA. This work is counterproductive and jeopardizes the access to these trails,” the organization posted to its Instagram – perhaps the best example to date of a VMBA chapter taking action.

Just last fall, another state forester told me: “I have had reports of people illegally cutting trails in Stowe for the past three weekends but it’s hard to actually catch them in the act.”

If you explore the woods around busy mountain towns such as Stowe, you will see metal “Unsanctioned Trail” signs appear, CYA misnomers that, ironically, only draw further attention to the damaged areas.

“We don’t keep any record of how many signs are put up or illegal trails are reported,” said Rebecca Washburn, Director of Lands Administration & Recreation for Vermont. When asked about what examples of fines or sanctions have been imposed, the only one she could cite is a well-publicized incident when a man cut 839 trees in Hazen Notch State Park, which abuts his property, to create backcountry ski glades. The man, Thomas Tremonte, was fined $75,000 in October, 2023.

As that incident illustrates, the problem lies not just with mountain bike trail building but also with glading for backcountry skiing. According to Washburn, there are more than 60 miles of sanctioned backcountry downhill trails in the state, ranging from Dutch Hill in the southern part of the state, to Rochester/Randolph glades in Braintree and Brandon Gap. Yet from sanctioned trails often emerge the unsanctioned ones.

In 2023, when a proposal to build a connector lift between Stowe Mountain Resort and Smuggler’s Notch Resort came up, the Barre District Stewardship Team (charged by the Agency of Natural Resources with making the decision) cited the likelihood of a new lift and trail increasing the already rampant illegal glading in the delicate high alpine forest as one of the reasons for rejecting the proposal.

In 2023, The Catamount Trail Association in partnership with the Vermont Dept. of Forests, Parks and Recreation released and promoted The Vermont Backcountry Ski Handbook, described as “a complete how-to guide for creating high quality, sustainable backcountry ski terrain in a cooperative fashion with forest land managers.”

It was as if the state were saying “Now, don’t go building illegal trails without permission, but if you do (wink, wink) here’s how to do it right.” The handbook could have been a great resource for ski areas and backcountry chapters and issued only to those who have permits in place. Why release and publicize that information for the general public?

These incidents, sadly, beg the question of whether or not the State of Vermont is tacitly complicit in the creation of unsanctioned trails. If not, why has the state not done more to curb this growing activity?

In Colorado, for instance, it is a Class B misdemeanor to build trails without consent on public lands, punishable by fines up to $5,000 and/or six months in jail—the same is true for all federal land. Yet, rogue trailbuilding became so prevalent that in 2022 the Colorado chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers offered a $500 reward for reports or information leading to a conviction of those responsible for illegal trail construction on public lands. In 2023, it upped the reward to $1,000.

Why should hunters (or anyone) care about a few mountain bike trails on public lands? A study cited by BHA showed that in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, that mountain biking ranked second only to ATV use in disturbing elk populations.

In British Columbia, the fine for illegal trail builds is $10,000 and the government publishes a toll-free number to report rogue trails.

In Vermont, fines are imposed only for timber cutting: $50 per tree that has less than a 6- inch diameter, $100 if it is 6 to 10 inches and on up to $2,000 for any tree over 22 inches. This law was inspired by illegal timber harvests, not trail building.

Vermont is at an inflection point where we need to do something to not only curb rogue trail building but to change the perception that it is tolerated.

Much of our trail networks and gladed ski runs were built without permission by passionate riders and skiers. Yet now, trails have evolved beyond rake and ride. There is state and federal funding to build trails (see page 13) and best practices for doing so. VMBA has 28 chapters. The Catamount Trail Association (the defacto umbrella group for backcountry skiing) has seven and that number is growing.

Certainly educating the public, creating and publicizing fines for illegal trail building and having a reporting system would be a start, when it comes to rogue trail building. But the state does not have the resources to police or enforce.

The change has to come from within. The trail groups themselves must be the ones to both change the ethic around illegal trailbuilding and enforce it.

The state can help by incentivizing this. What if there were significant fines that were widely publicized? What if, for instance, state or other funding was withheld from trail groups in any area where rogue trailbuilding was reported? What if the inclusion of say mountain biking or backcountry skiing in long range management plans was jeopardized by illegal trail building in those areas?

Don’t get me wrong: As a skier and a mountain biker and a hiker I am pro-trails. I have been an editor of Bicycling, of SKI and also the editor of Audubon. I am all for building trails. But that needs to be done legally and within the parameters of state and federal guidelines.

In American Places Wallace Stegner wrote this of Vermont: “There is something in its climate, people, history, laws — that wins people and loyalty, and does not welcome speculation and the unearned increment and the treatment of land and water as commodities. Here, if anywhere in the United States, land is a heritage as well as a resource, and ownership suggests stewardship, not exploitation.”

Illegal trail building or cutting, simply put, is exploitation—a land grab that reeks of entitlement.