Peter Macfarlane’s Epic Journeys

How a boat builder from Addison became the first person to paddle the Northern Forest Canoe Trail across New England, both ways.

Peter Macfarlane is not someone who does things the easy way.

Stepping into his barn workshop in Addison you see this right away.

At the center of the room, Macfarlane, 56, is bent over a 16-foot custom cedar-strip canoe, polished to be impossibly smooth on the exterior, with cherry gunnels and the boat builder’s insignia along with his company’s name, Otter Creek Smallcraft, under a rail.

A gray tabby cat flicks its tail as it watches him gently polish the newly-finished wooden canoe. Two chairs are set out, left over from the Scottish fiddle lesson Macfarlane taught last night, as is a book of fiddle tunes.

“It’s a funny thing to feel for an inanimate object, but by the time you spend 200 hours creating a boat, you have an intimate relationship with it,” says Macfarlane.

Peter Macfarlane is wiry, with white hair and an impish grin. He speaks with a gentle lilt, which hasn’t faded in the 16 years he has lived in Vermont. When he talks about paddling, his blue eyes light up and despite his white hair, he moves like a dancer—something he picked up from years of Scottish folk dancing and marathon whitewater kayak racing.

He’s been restoring and building cedar strip canoes since 1996 and is largely a self-taught craftsman. His first project was a half-destroyed vessel he salvaged from a woodpile. He and his wife Viveka restored it, “wrestling it back into shape,” and they still paddle it today.

He grew up in England, where he has paddled the 125-mile Devizes-to-Westminster kayak race in Southern England, along with a multitude of other paddling marathons. He’s a former slalom kayak racer who has been paddling competitively since he was 12.

Years on the water have given him a keen sense for how small adjustments to the shape of a hull or the width of a boat’s bottom will change its capacity to track in open water or navigate a rapid. Order a custom boat from him and he will ask for your height and weight to optimize everything from the angle at which your paddle strikes the water to the balance between the bow and stern as the boat sits on your shoulders during a carry.

He built the first boat of his own design, a 15-foot, flat-bottomed, 44-pound canoe, in 2007. Then in 2012, he set out to build an even lighter touring rig. He called that design, which yielded a stunning, asymmetric 14-foot solo canoe, Sylva. The original Sylva canoe was designed, shaped and lovingly finished specifically for the rugged rivers and streams of the Adirondacks, the Northeast’s deep lakes, Vermont’s rolling rivers and the scattered ponds of Maine.

“By the time I got the lines just right, it weighed just 35 pounds. I just knew that this would be the boat, and that paddling in my own boat would be a much more intensely personal experience,” says Macfarlane.

He had a plan for that first Sylva canoe: to celebrate his 50th birthday in 2013 he was going to paddle the length of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, a 740-mile trip from Old Forge, N.Y. to Fort Kent, Maine.

Over 28 days from May 19 to June 15, 2013, Macfarlane covered the length of the trail. Then, not satisfied with having completed the trail once in the conventional manner, in 2018 he decided to do it again.

But this time, Macfarlane suspected that he and his boat had it in them to do the canoe trail in a way no one had ever done before: by paddling upstream.

The Ultimate Test

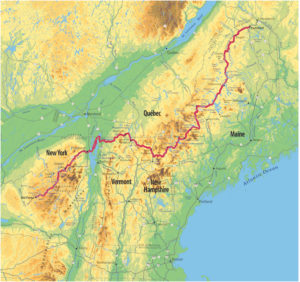

The Northern Forest Canoe Trail (NFCT) is the longest canoe trail in the country. It’s a network of 23 streams and rivers and 59 lakes and ponds that spiders across the Adirondacks and the northernmost regions of Vermont, dips into Quebec, traverses New Hampshire and heads deep into Maine’s North Woods.

Along the way the trail features 65 portages over everything from farm roads to rarely trafficked

wilderness trails. The longest haul is more than five miles and the most infamous is the Mud Pond Carry, a 1.7-mile slog through what can be thigh-deep mud in the heart of Maine’s woods.

The trail also follows some of the Northeast’s most scenic waters, including a section of the Mississquoi River between Enosburg Falls and Richford that is one of two designated Wild and Scenic river sections in Vermont. From the Saranac River in the Adirondacks, to the Clyde and Nulhegan in Vermont, the Androscoggin in New Hampshire and Allagash Wilderness Waterway in Maine, the trail offers a rare view of the Northeast’s landscape. Paddlers might pitch a tent on an island in Maine or camp in a field near grazing cows along Vermont’s Mississquoi. On Maine’s Allagash Wilderness Waterway, the trail follows shorelines that have sustained the Abenaki for centuries and which inspired Henry David Thoreau in his 1864 book, The Maine Woods.

The trail was established in 2006, based on traditional travel routes used by Native Americans, settlers and guides. Though much of it can be kayaked, it’s called a canoe trail to honor the traditional mode of transport. The trail spans private and public land and is overseen by a non-profit, the Northern Forest Canoe Trail, which maintains campsites, creates trail maps and coordinates access for paddlers. To date, an estimated 113 people have thru-paddled the trail from west to east.

28 Days, New York to Maine

In 2013, Macfarlane gave himself 28 days to paddle from west to east, the “downstream” route. He embarked on May 19 from Old Forge, N.Y. hoping for high water levels, long daylight hours and bearable black flies. Rather than carry a heavy tent, Macfarlane packed a hammock and tarp for sleeping and a small woodstove for cooking.

The first section of the trail takes paddlers through the eight lakes that comprise the Fulton Chain. With portages between them, many of the lakes are dotted with historic camps and homes, and the occasional lean-to or campsite, with camping on the rocky, fir-covered islands spread throughout the chain.

The first five days took Macfarlane through the heart of the Adirondacks, linking Fourth Lake, Raquette Lake and Long Lake before arriving in the Saranac Lakes region. On day three Macfarlane encountered his first Class II rapid on the Saranac River, called Permanent Rapids. After attempting a technical maneuver in a gorge, his boat was shunted sideways into a rock. “The audible crack is deflating,” he wrote in his journal that day. A 10-inch crack in the fiberglass on the interior of the boat was a warning that he heeded all the way to Chase Rapids on the Allagash River in Maine, which at class II is the biggest cascade paddlers navigate on the trip.

After five days and several carries around dams, the Saranac River spilled out in Plattsburgh and Peter took to the open waters of Lake Champlain. There, he embarked on a 32-mile crossing done by island hopping, paddling along the western shore of South Hero, then the eastern shore of North Hero before arriving at the mouth of the Missisquoi River, north of Swanton.

Most nights Macfarlane would sleep in his hammock suspended between two trees, at campsites along rivers and lakes, or on the occasional island. But the Northern Forest Canoe Trail runs through communities, towns and farmlands as well as wilderness and public lands. Its banks are as diverse as the rivers and lakes it follows. On nine nights, Macfarlane took shelter from deluges in motels, inns and private homes when strangers he encountered along the way invited him in.

The trip coincided with one of the wettest springs on record. “Parts of that trip were sublime, with beautiful paddling,” says Macfarlane, who acknowledged being tempted at times to bail due to the torrential rain. Furthermore, he chose to carry all of the food he would need for the first half of the trip, with a single planned resupply in the Connecticut Valley. On each portage, he estimates he hauled 90 pounds of supplies. And he was still hungry most days.

On day 10, he paddled down Lake Memphremagog and on toward Clyde Pond. On the Clyde River he was met with everything from rapids to placid waters and flooded woodlands. At times, the river was a pristine stream channeling through bog-lined northern forest. At others, it was deep with wide stretches as it passed through towns like East Charleston. Three days later, he was paddling under covered bridges and past paper mills on the upper Ammonoosuc in New Hampshire, headed for the rugged waters of Maine.

Through headwinds, early morning mist and wet conditions, he paddled onward, never failing to find beauty in the north country landscape.

“Even in dark times and struggles, there is a perverse sense of enjoyment I get out of overcoming difficulties and seeing where I can push myself,” he said. “Once I was confident in my boat’s ability to complete the trail, the question became: what magnitude of difficulty can I overcome?”

The scenery helped. One day in Maine, he arrived at a sandy campsite on the West Branch of the Penobscot, a great, wide, meandering river. “The next morning, after falling asleep in a torrential downpour, I awoke to radiant sunshine. The fragrance of balsam fir was everywhere as I slid my boat into the water to start the day’s paddle downstream, and it stayed. I saw moose grazing and birds of prey, far from any road that led anywhere. It was pure paddling pleasure.”

“You’re Paddling the Wrong Way!”

Once he completed the trail, MacFarlane’s body returned to work but, as he says, “my mind remained on the water.” Over the following five years, the allure of the Northern Forest gnawed at him. In spite of the nearly relentless rain, he had found a sense of calm and peace traveling by canoe. He’d also learned he was capable of tackling long days with a lot of mileage. “On a river trip, the rhythm of paddling gives you permission not to think. You have purpose and calm and I knew the day I finished, it was a case of ‘when’, and not ‘if,’ I would get back on the trail.”

As of spring 2018, no one had completed the trail going from east to west—and with good reason. Doing so requires traveling upstream on nine of 13 major rivers, including the Allagash, Raquette and Saranac. It also means finding a way to move upstream or portage around the biggest rapids of the trip.

“For me, the uncertainty in taking on a paddling trip of the scale and length of the Northern Forest Canoe Trail lies in the physical challenge, certainly, but also in the psychological challenge,” says Macfarlane.

His reason for doing so was simple: he wanted to replicate the sense of satisfaction he’d gotten from completing his first trip. This required testing his body and his boat in a new way.

Macfarlane had just 28 days to spare from his work as a boatbuilder and fiddle teacher and so was determined to paddle as much of the trail as he did on his first trip, averaging 26 miles of paddling per day for 28 days, often entirely upstream. For Macfarlane, doing so was a test of his willpower, craftsmanship, design and physical fitness. His primary training regimen? “Splitting and stacking enough wood to fill our empty woodshed,” he says.

He launched his canoe in Fort Kent, Me., on May 14, hoping to reach Old Forge, N.Y. by mid-June.

For much of the way, the currents were running against him. To paddle upstream, Macfarlane employed three traditional canoeing techniques: eddy hopping, poling and wading.

Where the river was deep enough for a paddle stroke, he zig-zagged his way up rapids by sprinting at intervals through the turbulence at the center of the river to the closest upstream “eddy.” These slackwater respites are often found behind the obstacles that create river rapids, like large boulders and logs. They pull a boat in, keeping it from being pushed back downstream. Macfarlane created a system of slingshotting himself up cascades, sprinting from eddy to eddy until he was forced by shallow water to pole or wade forward.

While navigating Chase Rapids on the Allagash, he battled the current as paddlers headed downstream calling out that he was headed the wrong way.

“Initially, I was able to eddy-hop. Sometimes, it was a thing of beauty,” he recalls. “Accelerating smoothly from the eddy, nosing into the current and maintaining momentum to carry me to the next eddy,” said Macfarlane. He’d make four or five moves, rest and scout his next move. In total, he paddled 3.5-miles up the class II rapid.

Where he couldn’t get his blade fully submerged in shallow water for optimal propulsion, he poled, kneeling in his boat and using a pair of old ski poles to push himself up rapids, double poling in the riverbed like a Nordic skier.

Where the current was too strong to pole or paddle, he got out of the boat and waded upstream, pulling the canoe with one hand and using a ski pole as a walking stick in the other.

This proved especially useful on the lower stretch of the Nulhegan River in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, where he navigated upstream between rocks and small waterfalls to emerge at a stretch of flatwater that he paddled to Nulhegan Pond, a quiet stretch in the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge.

Unlike on his last trip, this day was filled with radiant sunshine. “Negotiating this stretch of river, which I’d carried around the first time, with its cascades and granite boulders and pristine water, was physically demanding. I had a sense of accomplishment at the top of that rapid that I’d never experienced traveling downstream with my boat.”

When he found himself, on the last day of the trail lounging in the sunshine on the town beach at Fourth Lake in New York’s Fulton Chain, 11.5-miles from the trail’s western terminus, he felt accomplished but a little ambivalent about the journey.

He weighed the possibility that someone else had completed the trail in this direction in secret and whether, either way, the whole journey had been worth his while. In the end, the answer was yes, for the sense of physical accomplishment it gave him. He persevered through persistent upstream currents and unrelenting headwinds to reach his destination. It expanded his sense of possibility about where his canoes could go, and he learned that they were hardy. Like himself, the Little Canoe that Could emerged unscathed, if in need of a second coat of varnish after hundreds of miles of upstream travel, through rapids, swamps and bushwhacked portages.

When he arrived at Alger Island, just before the passage to Third Lake in the Adirondacks, he was met by Viveka, sterning his first canoe, Lutra, with two friends and a picnic basket between them, ready to paddle with him into Old Forge after a glorious lunch on the island, complete with a white table cloth.

There’s Always Another River

A year out from his journey, Peter is still dreaming about adventurous canoe routes. His new fascination is with river trips that start and end at Lake Champlain and the Otter Creek, which lies just a few miles from his home in Addison. “Imagine paddling down the Richelieu, to the St. Lawrence, the St. Francis and on to Lake Memphremagog and back to Lake Champlain,” he says.

He’d gladly do the Northern Forest Canoe Trail again, he admits. Since 2013, he’s volunteered as a

Northern Forest Canoe Trail steward, helping to maintain campsites and collect information about trail use for the nonprofit. He cares for the roughly 10-mile section from the southern tip of North Hero to the mouth of the Mississquoi. “Having got so much out of the trail on my first trip, I thought it would be good to put something back into it, so I adopted the nearest bit to home and have cared for it since,” he says.

“The Northern Forest Canoe Trail offers the whole gamut of paddling, except for saltwater,” he reflected. “I’m not aware of another trail like it. You’ve got highly populated lakes like the Fulton Chain in the Adirondacks, near Old Forge. You’ve got rivers that flow through inhabited areas, like the Saranac, where you’re paddling past houses along the banks. Then you’ve got agricultural environments along the Mississquoi and Connecticut Rivers, where cows come to graze by your campsite and there are fields right up to the riverbank.”

Those industrial and human-shaped zones are interspersed with some of the wildest waters of the Northeast. “You have too the small streams in the wilds of Maine and big magnificent rivers like the West Branch of the Penobscot, the St. John. You have managed wilderness with designated campsites, and then you find these wild places in Maine that are not managed as such but are effectively more wild, more remote and more rugged. You can battle four-foot waves on the sixth largest lake in the country [Lake Champlain] and class II rapids on the Allagash,” said Macfarlane.”

For his part, he doesn’t plan to attempt the trip upstream a second time. “Frankly, it was a bit of a stunt,” he said with a laugh. “It really tested me.”

Reflecting further, he added, “Aside from the cursing at algal rocks—and there were quite a lot of both, cursing and slippery rocks—I really enjoyed the upstream travel and my surroundings.”

To the intrepid paddler looking to repeat that east-west trip? He offers this: “Good luck.”

For more about New England’s paddler’s trails and trip suggestions, see “3 Epic Paddler’s Trails” or “10 Great Paddling Trips from Easy to Epic.”

Featured Photo Caption: At 740-miles long, the Northern Forest Canoe Trail offers diverse paddling on 13 major New England rivers. Here, Peter Macfarlane enjoys a misty morning on the West Branch of the Penobscot in Maine on his May 2018 thru-paddle. Photo by Peter Macfarlane