The Keepers of the Moosalamoo

Eds. note: This article first appeared in the Sept./Oct 2021 edition of Vermont Sports. On March 27, 2022, Tony Clark passed away. Our hearts go out to his family and friends and we are ever grateful for the legacy he leaves Vermont.

On a warm evening in August 2021 Britta Clark assembles pizzas at a folding table near the pond at Goshen’s Blueberry Hill Inn. Her brother Oliver slides them into the outdoor pizza oven. Their parents, innkeepers Tony and Shari, wander around chatting with guests.

Near the pond, a firepit smolders. Children chase each other through rows of blueberry bushes popping ripe berries in their mouths as they go. The boughs of the apple trees are already hanging low with ripening fruit.

The setting sun glints through the leaves. The sounds of a fiddle come from a grove where the bluegrass band Bloodroot Gap has set up beneath a tent. The audience – largely locals —sits around in folding chairs, tapping feet and munching on pizza, all you can eat for $20. The house salad is locally grown, and the ice cream is from lu.lu. of Vergennes.

Surrounded by open fields and a big western sky, the gardens and grounds of the Blueberry Hill Inn are about as idyllic as Vermont gets.

But Blueberry Hill Inn could be any inn, on any dirt road in Vermont. What sets it apart are the trails that lead around and away from the inn’s own 60 acres. Some meander down to the quiet waters of Silver Lake and its 15 campsites. Other trails continue on to the thundering Falls of Lana, or to Branbury State Park and its beach on Lake Dunmore. Some trek up Mt. Moosalamoo, named by the Abenaki “Mozalamo” or “call of the moose,” and Rattlesnake Cliffs.

Other trails around the inn are mowed clean of nettles. Wide enough for two to run side by side, they wind through the forest and across wild blueberry fields or up the steeps of Romance Mountain. These trails, maintained by the inn, have hosted some of the toughest endurance events in the East, including the now-defunct 60K American Ski Marathon, the Moosalamoo Marathon, the current 888k Infinitus and its shorter races that span a week of events, and the local favorite — the Goshen Gallop 10K and 5K trail runs which have gone on for four decades.

These trails have also produced some of the most accomplished endurance athletes in the state. Chris “Flash” Clark grew up skiing here and nearly made the 1994 Olympic cross-country team.

Now Britta Clark, his half-sister, is one of the country’s top trail runners. In August, the 27-year-old placed second in the USATF Trail Running Championships, running the Ragged Mountain (N.H.) 50K in 5:47. Earlier this season, she also finished second at the Catamount Ultra and won the marathon distance of Infinitus on her home turf, placing 3rd overall for men and women.

I think I got into trail running when I moved back here after college,” she says. “Now, I’ve run every trail around here.”

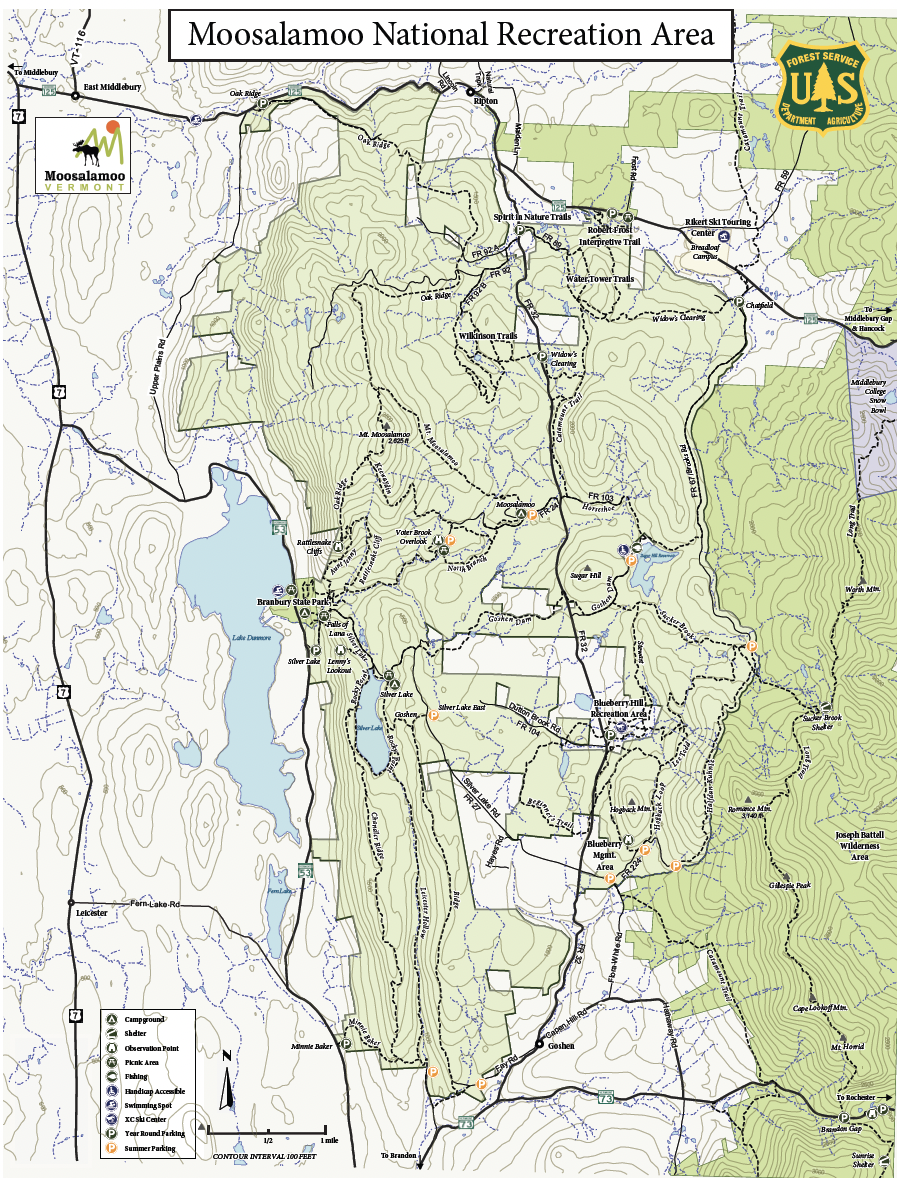

Which is saying something as there are over 70 miles of trails that crisscross the Moosalamoo National Recreation Area, a playground of 16,000 acres made up of Green Mountain National Forest and pockets of private land. The Moosalamoo comprises a rectangle formed by the Long Trail to the east, Lake Dunmore to the west and bordered by Route 125 to the north and Route 73 to the south. To the north, it sidles up to the Breadloaf Wilderness. Most of it sits within the 400,000-acre Green Mountain National Forest.

And what sets Blueberry Hill apart is that the Clark family has helped to preserve the trails and the Moosalamoo National Recreation Area, one of just 44 such areas in the country, as a relatively undiscovered playground.

[See related: 10 Things to Do in the Moosalamoo]

It is a playground that Britta is now looking to share with a new generation.

Rebuilding a Ski Area

In 2004, Britta’s father, Tony Clark, was instrumental in getting the Moosalamoo region nominated for a World Legacy Award. Then, in 2006, he helped get the Moosalamoo designated a National Recreation Area, one of two in the state (White Rocks NRA, near Bennington, is the other) and just 44 in the U.S.

Peter Miller, the Colbyville, Vt, photographer and author once described Tony Clark as “Not as big as he is strapping, a ruddy-cheeked outdoorsy type who looks like he was brought up on Yorkshire Pudding, bubble and squeak, Harris Tweed jackets and hikes in the mountains.”

That description still apt though Tony is now a fit 77. But the image of the affable British innkeeper with a cultured Old World demeanor undercuts the quiet intensity with which he pursues just about anything that catches his interest: from innkeeping to cross-country skiing, from cutting trails to preserving a piece of Vermont for future generations.

A Welshman and son of a wine exporter, Tony grew up in Bordeaux, France. He came to the U.S. in 1964 to visit his brother who was studying at Harvard. He ended up staying to teach French at the Eaglebrook School in Deerfield, Ma. There, he met his wife, Martha, a fellow teacher. “She was the one who found the farm in Vermont and brought me here,” he says. That was in 1968. “Back then, Vermont was attracting all sorts of back-to-the-landers and farmers – sort of like it is today,” he recalls.

Blueberry Hill was in shambles at the time. It had been the site of an old inn and small ski area with two rope tows: one on a beginner slope and another running up the steeps of Hogback Mountain. The carcass of an old truck that once powered a tow still sits in a clearing. “There were abandoned cars everywhere, the inn’s pipes were frozen. The sewage pipes actually ran through the hulk of an old buried car,” Tony recalls.

The couple had a vision to restore the place and to be a part of the local community. “We had every animal you could imagine… chickens, donkey, you name it,” Tony remembers. There were three working dairy farms in the area. Bingo night in the tiny town of Goshen (current population 160) was the monthly gathering spot for the neighbors.

The Clarks went to work renovating the 1813 clapboard farmhouse and former inn and reopened it for business, along with the Outdoor Center, in 1971.

A conversation with Johannes von Trapp of the Trapp Family Lodge inspired Tony to ski more himself and to start cutting cross country trails. “I remember some nights being out there grooming trails at 2 a.m. and looking back at the tracks and thinking they were too beautiful to be skied on,” he says.

Pretty soon the U.S. Forest Service paid a visit to inform the Clarks that some of the trails were actually on public land. “We hadn’t a clue,” Tony remembers. That resulted in a friendly discussion, the first special-use permit by the USFS in Vermont, and an ongoing partnership to bring recreation to the area.

At the time Nordic skiing was growing and other than the Trapp Family Lodge, Viking Nordic Center and Woodstock Inn, there were no other cross-country ski areas in Vermont. “Pretty soon we were packed with skiers. We had 300 pairs of rentals,” Tony recalls.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Blueberry Hill saw 8,000 to 10,000 skier days a season. Blueberry Hill’s ski touring teaching program catered to more than 1,500 local schoolkids. As an offering to the neighbors, all Goshen residents and all school children who lived within a 20-mile radius, skied for free.

The Blueberry Hill Outdoor Center, a large barn-like structure across the dirt road, began hosting races. They ranged from the down-home invitational Pig Race (ending with a pig roast at the Inn), to the highly competitive Dannon Series, to the 60K American Marathon, sponsored by Hennessy Cognac. That race, one of the longest in the U.S. at the time, drew over 1,000 competitors in its heyday, thanks to the fact that you could opt to ski just 20K (to the Breadloaf Campus) and earn a bronze medal, or go 40K for a silver, or ski 60K all the way back to the Otter Valley High School in Brandon for a gold.

Participants in the first event in 1978 boarded 22 buses at the Otter Valley High School in Brandon and headed to the start in South Lincoln, where John Caldwell presided as race director and then-Lt. Gov. Madeline Kunin was slated to ring the start bell. The course followed the VAST trails, parts of the Catamount Trail, the Rikert Nordic trails and the Blueberry Hill trails. The race became part of The Great American Chase series and continued for more than 10 years. By 1986, Tony had inspired local volunteers to bake goods and serve them at aid stations along the way.

“Back then there were plenty of volunteers and sponsorship money for that sort of race,” Tony remembered, “and we had snow!” But soon more ski areas began to come online. Sponsorship money became scarce. Volunteers grew tired. Winter snow cover began to dwindle. Tony and Martha parted ways.

Preserving the Region

Shari Brown was 24 and on an inn-to-inn hiking tour with her aunt when she first came to Blueberry Hill Inn. “Tony offered me a job then – he offered everyone a job, back then. And still does,” she adds with a laugh. She took it and started in 1987. Shari had a degree in tourism and recreation management and an interest in gardening. She became Tony’s partner in all senses and began planting the sunflowers, the phlox and the profuse garden beds that cocoon the inn all summer. Soon daughter Britta and then son Oliver arrived.

While the winter ski business began to dwindle, the inn’s visitors continued to come and raved about the inn, the grounds and the surrounding forests and lakes of the Moosalamoo.

It was a region that Tony was already setting out to preserve. In 1989, he gathered representatives from Branbury State Park, the U.S Forest Service, the local utility (then CVPS, now GMP), chambers of commerce and other inns to create a single map of the region, showing all the trails. They also formed the Moosalamoo Partnership. Soon the organization was applying for grants, building trail signs and interpretive panels and promoting the region.

“It must have been one of our guests who nominated us for the award,” Tony, a subtle master of promotion, says demurely referring to the World Legacy Award.

The World Legacy Awards were put on by Conservation International and National Geographic Traveler, and presided over by Queen Noor, of Jordan. In 2004, the Moosalamoo region was one of 12 finalists worldwide for the awards, which recognize the sustainable stewardship of exceptional destinations. The ultimate winner was a volcano in Lombok, Indonesia.

With that award nomination, Tony brought the Moosalamoo to the attention of Sen. Patrick Leahy and Sen. Jim Jeffords, pointing out the immense recreation opportunities the area offered, all within a 5 hour drive of 80 million people. “One day I get this call: Meet the Senator at the airport,” Tony says. Soon, he, Sen. Jeffords and his aide were flying over the Green Mountains. “It was spectacular: Imagine me, an innkeeper, flying in a private plane with a U.S. Senator,” he says modestly. “When we landed, Jeffords says, ‘Tony, you got your National Recreation Area.’”

In 2006, George W. Bush signed the New England Wilderness Act, which designated the Moosalamoo as a National Recreation Area.

With that designation came federal funds. Maps were produced. Signs went up. More than 40 bluebird houses were installed and a birding guide to the area was produced. Apple trees were planted and the wild blueberry fields maintained. The trail network was expanded.

But then, in 2008, heavy rains demolished many of the bridges that were key to the cross country ski network and to the Robert Frost Trail and they also flooded the popular Leicester Hollow area washing out the trail. Three years later, Hurricane Irene destroyed more trails and even tiny Dutton Brook, which flows near the inn, rose 8 feet, washing out the road.

But then, in 2008, heavy rains demolished many of the bridges that were key to the cross country ski network and to the Robert Frost Trail and they also flooded the popular Leicester Hollow area washing out the trail. Three years later, Hurricane Irene destroyed more trails and even tiny Dutton Brook, which flows near the inn, rose 8 feet, washing out the road.

“It was just too expensive to rebuild the bridges,” Tony recalls. Without the bridges, they couldn’t groom the ski trails. The area became more of a backcountry touring destination. “It’s funny how things come full-circle,” Tony muses.

But other trails in the Moosalamoo continued to be developed. Patrick Kell, then executive director of Vermont Mountain Biking Association (VMBA), led a $150,000 effort, fueled by manual labor from the Vermont Youth Conservation Corps, to build a 10-mile singletrack loop starting at Silver Lake, following the ridgeline of Chandler Ridge overlooking Lake Dunmore. And in 2014, crews finished work on a 7.6-mile section of the Oak Ridge Trail, off of Route 125.

That Oak Ridge trail has since been extended as a mountain biking trail all the way to the Moosalamoo campground with new flowy sections and a one-mile loop around the campground.

“Our goal is to eventually connect the Oak Ridge Trail to Chandler Ridge,” says Sue Hoxie, the executive director of the Moosalamoo Association. Just two miles remain. The challenge is finding a way to cross either a deep ravine or wetlands, and a small chunk of land owned by Green Mountain Power. But a solution appears to be at hand. Once connected, the Moosalamoo would have one of the longest continuous point-to-point singletrack trails in the state, running close to 20 miles from Route 125 to Route 73. There are plans in place as well to map a Grand Tour of 25 miles of trails and Class 4 roads that would be a point-to-point.

The Next Moosalamoo

“I do feel some regret for what we built,” Tony Clark admits, as he sits in the now-quiet dining room of the inn, facing a massive stone fireplace, a plate of the Blueberry Hill’s famous cookies and lemon squares before him on the table.

“The sense of town spirit we first saw here no longer exists. If you look up and down the road now you see second homes. They belong to perfectly nice people — many who stayed at our inn— but they don’t live here year-round, they are not part of the community,” he laments. “There are no more dilapidated cars in the fields. It’s become all rather twee,” he says with wry chagrin. This from the innkeeper whose grandfather made a business out of selling marzipan-stuffed prunes.

But then he brightens. “But farms are coming back – we now have a goat dairy farm here,” he says, referring to Ice House Farm just down the Goshen-Ripton Road, which produces yogurts. Republic of Vermont, which produces local honey and maple syrup is also right down the road.

Still, Tony recognizes the successes that the Moosalamoo Association and its supporters have accomplished. RJ Thompson, of Vermont Huts Association, sits on the Moosalamoo Association board and sees the opportunity for a backcountry hut in the Moosalamoo, a location that’s close to the Brandon Gap ski trails and the proposed Velomont Trail. Moosalamoo Association board president Angelo Lynn has been working with Middlebury College to see if the area can qualify for a nationally recognized Dark Sky designation. Ashar Nelson, another board member and president of the Addison County Bike Club, has been working on plans to connect the Chandler Ridge and Oak Ridge trails. The new North Country Trail, which starts in North Dakota, is slated to run 4,700 miles with its last section crossing the Moosalamoo to connect to the Long Trail.

In 2017, Senator Leahy wrangled a clause into the appropriations bill designed to provide annual funding to all NRAs established since 1997. That amounted to three: the Moosamaloo National Recreation Area, the Mt. Hood National Recreation Area and the Land Between the Lakes, in Kentucky and Tennessee. It was one thing that Sen. Leahy and Kentucky’s Sen. Mitch McConnell, could agree on. Since then, it has funneled more than $1.5 million to the U.S. Forest Service to maintain and upgrade parts of the Moosalamoo.

In spring of 2021, Sen. Leahy presided over the reopening of the Robert Frost Trail, now the state’s second-longest universally accessible trail. The trail, with more than a quarter-mile of raised boardwalk made of durable materials, cost nearly $650,000 to build.

“The Frost Trail is just one of a large number of superb and widely diverse recreational opportunities available within the area, at an accessible ‘Vermont scale’ that can be enjoyed by all,” Sen. Leahy said at time.

And Britta Clark has a vision for the Blueberry Hill Outdoor Center to become the visitor center to access the region — an educational outpost and entry point. In 2020, the Center became a non-profit. Trail fees no longer exist, but donations are encouraged.

Britta is both a product of the Moosalamoo and, to an extent, the future of it. After graduating from Bates, she has been working on her Ph.D. at Harvard in political philosophy with a narrower focus on what she says is “intergenerational justice with a specific focus on climate-change related questions.” It’s a field of study she says, “is pertinent to our present environmental moment and to this space and making sure it’s around for future generations and accessible to them.”

Britta returned to Vermont in 2018 after spending two years completing a Fulbright scholarship in New Zealand. Her master’s thesis focused on New Zealand Parliament’s 2017 passage of the Whanganui River Settlement Bill. The bill granted legal personhood to the Whanganui River and in doing so gave the river all the rights, powers, duties and liabilities of a legal person. It’s a field of study that’s impacted her way of thinking.

“A lot of contemporary political philosophy doesn’t take quite take seriously the idea that there are particular places where justice demands that those places are kept around continuously. It can’t quite accommodate the idea that ‘this place’ – be it Blueberry Hill or a people’s ancestral homeland, or say the Arctic Wildlife Refuge – that these particular places, ought to stick around,” she says.

She sees herself staying involved, perhaps finding a teaching job in Vermont, and making sure that Blueberry Hill and the Moosalamoo are there for future generations. She’s seen trail use double during the Covid pandemic and more gravel riders and bikepackers come through than ever before. She’s in talks with groups about establishing a bikepacking event or a gravel race.

But there’s a higher calling, as well.

“These days I’m more concerned about the economic and social impacts of climate change. These impacts, along with changes in weather patterns, will result in less snow, making accessing nature more difficult,” she says.

“There are a lot of local kids who have never skied. I think those are the people whom I would like to see here,” she adds.

Opening photo of Silver Lake in the Moosalamoo National Recreation Area by Caleb Kenna.