Taking A Ride Through History With The Old Spokes Home’s Glenn Eames

He’s ridden around the world and run Burlington’s most eclectic bike shop. Now, Glenn Eames is busy showcasing one of the country’s foremost bike collections – his own.

At 67, Glenn Eames has ridden around the world, but he’s only ridden in one organized century ride. “It was out of Billings Farm in Woodstock, in 1992, and I can’t remember exactly where we rode,” Eames says. But he can tell you what bike it was on: a vintage “Ordinary” bike, also known as a high-wheeler or “penny farthing,” from the 1880s.

Dressed in period clothes and perched high atop the big wheel, he rattled along for 100 miles. “It’s not a particularly comfortable ride, but I like to get out on these old bikes every so often,” says Eames, with characteristic wry humor.

Eames bought his first bike, a Raleigh, in 1974 and a few years later, a penny farthing, a prop out of the display window of a sports store in New Hampshire. That was the start of a life-long obsession with bicycles.

Transforming Lives

When he talks about bikes and the history behind them, Glenn Eames does so with the passion of a teenager talking about his first fat tire ride. “Before the bicycle, people rarely married anyone who lived beyond a 10-mile radius of their home. Suddenly, when the bike came around, men—and women—could travel 50 or 60 miles by bike and go when and how they liked.”

When he talks about bikes and the history behind them, Glenn Eames does so with the passion of a teenager talking about his first fat tire ride. “Before the bicycle, people rarely married anyone who lived beyond a 10-mile radius of their home. Suddenly, when the bike came around, men—and women—could travel 50 or 60 miles by bike and go when and how they liked.”

He pauses, then adds what, for him, is a recurring refrain: “Bikes transform your life.”

Bikes transform your life. Few people can say so with such conviction—or authority—as Eames. For the man who was the force behind Burlington’s iconic bike shop, The Old Spokes Home, those words ring true on many, many levels.

“I was in my twenties, and not particularly healthy and smoking, when I first started riding,” says Eames, as he rests his hand on the saddle of one of his 60 or more bikes. “Cycling probably literally saved my life.”

Eames quit smoking when he started riding. He also met an avid cyclist named Mary Manghis. They were both living in New Hampshire at the time, each running small shops (Eames, a party store; Manghis a natural foods restaurant). They began touring by bike, first making forays into Vermont and around New England, then planning trips that led them farther afield, to Europe, Asia and Africa.

Eventually, the couple sold their two shops, put their belongings in storage and set off on a two-year bike-trip around the world. When they came back, they moved to Burlington where Eames worked at SkiRack for 14 years before starting the Old Spokes Home in 2000. In January, 2015, Eames sold the shop, gently passing it on like a proud father might, to the best owners he could find: his neighbors who had been operating Bike Recycle Vermont just across the street.

Over the years, the Old Spokes Home had become a Mecca of sorts for serious cyclists and a place where frame builders such as Hunt Manley (Budnitz Bikes) and Hubert D’Autrement came for both work and inspiration. Eames had sprinkled parts of his collection throughout the shop but on the second floor he created “The Bike Museum,” with bikes ranging from an 1868 velocipede to a 1930s Peugeot racer, a 1949 Rene Herse randonneur to a 1968 Schwinn Orange Crate.

“After I sold the shop, I left some there and moved some to my barn. But I didn’t really know what to do with them,” said Eames.

Bill Brooks, an avid cyclist and former triathlete, did. The historian and executive director of Middlebury’s Henry Sheldon Museum proposed an exhibit to Eames. The Sheldon’s Assistant Director, Mary Manley (whose son Hunt is the builder for Budnitz Bikes) pitched in.

Three years later in 2016, on the anniversary of the first bicycle patent, “Pedaling Through History“ was an exceptional display of one of the country’s most interesting bicycle collections, made all the more fascinating when Glenn Eames is there to guide you through it.

Bicycling’s Age of Invention

Eames curated the exhibit of his bikes and collectables at Middlebury’s Sheldon Museum, the oldest community museum in the country. As he walked through rooms featuring period furniture from the late 1800s (and even Henry Sheldon’s bed and slippers), Eames practically jumped to point out a bike, an innovation or a photo on the wall.

The design and technology surrounding bikes went through a lightning-fast evolution in those early years, wooden rims and spokes giving way to forged metal and rubber.

The design and technology surrounding bikes went through a lightning-fast evolution in those early years, wooden rims and spokes giving way to forged metal and rubber.

Eames pointed out the tensioned spokes, suspension, chain drives, split saddles and gearing. Photos on the walls of the exhibit showed early cyclists wearing jerseys and shorts, kits that look strikingly modern. Races drew thousands of spectators and high stakes wagers. For safety as well as camaraderie, cyclists of that early era would ride in groups, clad in club uniforms, with buglers leading the charge and using the calvary calls to what today would be called a peloton to indicate when to mount, dismount or slow down. Display cases show the early lights cyclists used, horns, bugles and whistles.

Pointing to various bikes, Eames described how in a matter of just a few years, the velocipede gave way to the penny farthing or “Ordinary” bike, whose large front wheel came in as large as 62-inch diameter, because, in those days before gearing, larger wheels could go faster.

“Between 1866 when a Frenchman named Pierre Lallement filed the first patent for a bicycle and 1870 when the Franco-Prussian war broke out, there was the most amazing boom in cycling in Europe,” said Eames.

Lallement, who had worked in a shop making baby carriages in France, moved to New Haven, Conn., in 1865 and began to ride a new contraption of his design. He filed for, and was awarded, the first bicycle patent on November 20, 1866 but he couldn’t interest any American company in producing his “velocipede,” so he went back to France. A year later, the bike craze took off in America and in 1869 the patent was bought by a man named Calvin Witty. (Witty later claimed in a court dispute he spent $10,000 to secure the patent, an amount he recouped as he not only went on to produce his own bikes but also collected $10 in retroactive licensing fees for every bike built by another manufacturer.) “In just one year, the bicycle was a huge fad in America and Witty became a rich man,” said Eames. According to historian David Herlihy, Witty even marketed his bikes to women, hiring a top woman rider as an instructor, holding “ladies-only” classes and keeping bloomers (a first step toward liberating women from long skirts) on hand for those who wished to try the new contraption.

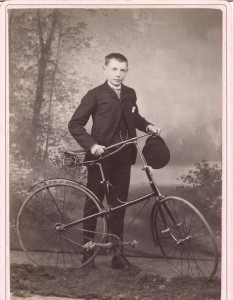

Eames paused at one of the earliest bikes in the exhibit, a serpentine velocipede most likely ordered by the traveling acrobat and stunt riders, the Hanlon brothers, in 1868. A precursor to the high wheeler it has two more equal-sized wheels. “I saw this in an auction but it was painted black but I had a pretty good idea of what it was,” he said with reverence. “It turned out to be one of the original Calvin Witty-built bikes, and one of only two such bikes in existence,” he said with reverence, noting the original 1866 Lallement patent stamp and license number, 434. How does he know it’s one of two? “Well, for a time I owned the other one as well,” Eames confessed.

Eames is reluctant to share what he paid for the bike or estimate what it is worth. “For me, it’s not about the dollar value but more about the historical value of each bike I buy,” he said. He works closely with other collectors, such as Toronto’s Lorne Shields (who loaned many images and smaller objects for the exhibit) to scout out bikes from around the world and bids on them at auction.

But to put it in perspective, in May, 2016 Sotheby’s sold an 1879 George Singer penny farthing racing bicycle at an auction in Monaco for 6,435 pounds — approximately $8,333.

“Glenn’s is one of the more important in the United States,” says Shields. “In terms of overall, balanced collections, I’d say there are maybe 10 really serious collections and his is among the cream of them.” Shields, along with the famous collector and concert musician, Pryor Dodge, have made up that elite crew.

But unlike Shields, or even Dodge, Eames is not just a collector but a passionate cyclist who has immersed himself in every aspect of cycling history. “He’s an educated collector. He reads and knows the history of the bicycle and he’s collected the surrounding things, like headlamps” says Shields, who gave the bulk of his bicycle collection —50 or 60 vintage bikes—to the Canada Museum of Science and Technology in Ottawa several years ago but has kept his collection of bicycle accessories, photos and lithographs.

“But it’s not about money,” Shields continues. “When you are a collector, it’s part of who you are. There’s the pride, the effort and money you’ve put into creating the collection, the stories and the collecting instinct.”

Of Bikes, Brothels and Speed Records

Eames has that collecting instinct and for every bike, a story.

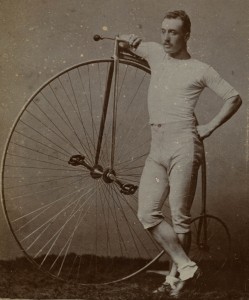

In one corner of the exhibit, next to a sleek high wheeler wais an image of John Keen, a fit man in a skin-tight kit that looks remarkably contemporary. In the 1870s, Keen was the fastest man in the world. It was reported that more than 12,000 people showed up to see him compete in one event and he purportedly once rode 50 miles in 3 hours, 9 minutes—yes, on a high wheeler.

In one corner of the exhibit, next to a sleek high wheeler wais an image of John Keen, a fit man in a skin-tight kit that looks remarkably contemporary. In the 1870s, Keen was the fastest man in the world. It was reported that more than 12,000 people showed up to see him compete in one event and he purportedly once rode 50 miles in 3 hours, 9 minutes—yes, on a high wheeler.

“Keen was a builder and innovator too,” said Eames. “He invented the rat trap pedals with toe clips, and advanced the use of ball bearings and drawn and tapered tubing,” he says, pointing to the high wheeler on display. In 1878 Keene and four other racers came to the U.S. to introduce high wheel bike racing. “Keen rode a 55-inch Eclipse,” Eames noted, then pointed to the bike in front of us. “This is a 55-inch Eclipse that came from southwestern Massachusetts. There’s a very good chance that this is Keen’s bike. I can’t prove it but it’s very unusual that this level of technology from the 1870s is even in this country at all.”

Next to that bike was an 1899 Tribune Blue Streak, a racer with drop bars and 30-inch wheels, similar to what Charlie “Mile-a-Minute” Murphy, used to become the first to break the 60-second mile in 1899. “He did so by laying a two-mile path of boards along the tracks of the Long Island Rail Road and drafting behind a locomotive,” Eames said. “It was quite the spectator stunt.”

One of Eames’s favorite stories involves the yellow Stearns “safety” bike, the bike most of us now consider the classic configuration, so named because it was far safer than the high-wheelers.

“I got a call from a gentleman who had the bike in his garage. It had been his grandmother’s and when he told me her story, I knew I just had to have it,” said Eames. He glances around the room to gauge his audience before he continues. “She was the owner of a very successful brothel in Aberdeen, one of the roughest lumber towns in Washington state. She smoked a cigar, had a pet rooster and rode this bike to and from work. She was quite the character.”

On a table nearby sat “How I Learned to Ride a Bicycle” a small book by the suffragette and temperance reformer Frances Willard. Eames picked it up. “This was a woman whose health was failing so, in her 50s, she learned to ride a bike and it was the most liberating experience for her,” he saiad.

I open the book and it fell randomly to a page where Willard wrote:

“That which caused the many failures I had in learning the bicycle had caused me failures in life; namely a certain fearful looking for of judgment; a too vivid realization of the uncertainty of everything about me; an underlying doubt—at once, however (and this is all that saved me), matched and overcome by the determination not to give in to it.”

Though Willard’s book is ostensibly about riding a bike, it is, to use one of Eames favorite words, much more about transformation and how bikes can and do change lives.