Sled It Ride | East Thetford Vet Wraps Up 20 Years as a Volunteer At the Iditarod

Some Vermonters take a break from winter by vacationing in warmer climates.

Not Charlie Berger.

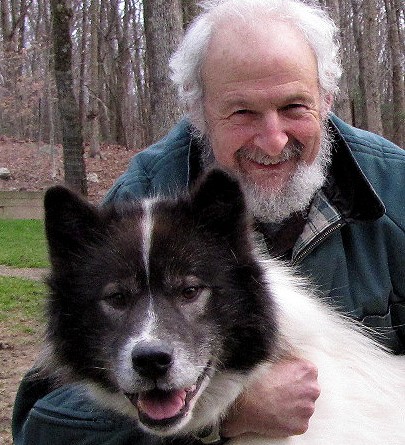

For the last 20 years, the 73-year-old East Thetford veterinarian has spent weeks in the frigid climates of Alaska and Canadian Yukon, volunteering his medical training at long-distance sled dog races including the legendary 1,049-mile Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race and the 1,000 mile Yukon Quest.

This will be the first year since he began volunteering that Berger will not be an on-course vet (he’s dealing with fractured ribs from a fall), allowing him time to reflect on his efforts and share stories from the trail.

Born in Brooklyn and educated at Cornell University, Berger bought a home in Vermont in 1971 and for several years split his time between the Upper Valley and Berkley, California, before making Vermont his full-time home in 2003. He practices at River Road Veterinary Clinic in Norwich.

Although Berger has lived in the lower 48, he has always had an interest in remote areas, which led him to spend time canoeing in Alaska and Canada’s Yukon. Some 20 years ago, when he discovered that the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race was in need of veterinary volunteers, he jumped at the opportunity. Since then, Berger has volunteered at the iconic race, performing a host of duties, including the essential pre-race physical examinations and exams at each of the checkpoints.

The Athletes

In order to compete in long-distance races, the dogs must consume 12,000 calories each race day—the equivalent of 24 Big Macs—eaten in frequent small, meals consisting of protein, fat, carbohydrates, and fiber; and often including local moose or salmon. Berger said there is a misconception that Alaskan huskies, the predominant racing type of dog, are big dogs. Actually, they average 45 pounds each. Alaskan huskies have been bred for more than 75 years for endurance and speed and to eliminate aggression.

Berger, an animal lover, is aware of the criticism levied at the sport. He wants to dispel the notion that sled dogs are mistreated during long-distance races.

“Man and dog have been friends and working companions for millennia,” he said. “These dogs have been selectively bred to do their job. We’ve made these dogs into incredible running machines that can run four or five marathons a day, for 10 straight days, in 40-below-zero weather and, near as we can tell, enjoy it.”

Although Berger has never been a musher, he appreciates the bonds that the racers form with their canine companions. “I think man and dog ought to explore all their potential as best they can,” he said. “I think dog and man should do more than just sit on the couch and watch re-runs. These dogs don’t make the greatest pets. If they didn’t run, they wouldn’t exist.”

On the Course

At the checkpoints, mushers aren’t obligated to spend more time than is needed to ensure that they have enough equipment and their dogs are healthy, so conversation is minimal and mostly involves the weather and course conditions. Occasionally overtired mushers will discuss their sleep-induced hallucinations, including seeing bridges or little people hiding in the trees. The pre-race physicals Berger conducted involve drug testing and electrocardiograms, while the mid-race checkpoints look for physical problems sustained during the event. Potential problems include respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, as well as leg and foot problems. There is also the potential for stress-induced stomach ulceration, and undetected cardiac issues. Berger worked in tandem with a course judge and both of them had the right to order mushers to take dogs out of the race, although he said that rarely happened.

“The mushers are more concerned than we are,” Berger said. “You never get resistance from mushers about dropping dogs.”

While the race garners international attention, working the Iditarod does not include staying in four star hotels, in fact, far from it. Since the race goes through roadless areas, Berger generally bedded down on the floor of post offices or high school gymnasiums, sometimes finding comfort on a bale of hay in a tent, as he went from checkpoint to checkpoint, examining the dogs throughout the course of the race. He mainly subsisted on trail food although some towns have cafés where volunteers can grab a greasy hamburger.

“It’s a little bit of madness, for sure,” he said.

But the madness is worth it. Berger said he has always been fascinated by dogs and their physical abilities, though his enjoyment of the Iditarod and other races goes beyond that.

“You always meet a lot of very, very offbeat, interesting people from many cultures and lifestyles,” he said. In addition, Berger has always enjoyed visiting remote locations and even produced a documentary called “Yukon Journal” on the people he has met there. “The glory and beauty of the north is a fantastic experience,” he said. “It’s an incredible opportunity to see remote and spectacular landscapes.”

Berger won’t be at the Iditarod this year, but that doesn’t mean he won’t be making a return trip to Alaska. “There’s a lot I miss about it,” he said “the excitement, the dogs and the people. These days I sort of prefer lecturing and going to Costa Rica or Africa for the winter, but that doesn’t mean I’m finished. I’ll probably do it again.”