This Vermont Athlete Is Confronting Climate Change

Last August, Pavel Cenkl ran 360 kilometers above the Arctic Circle. This summer, he’ll bike and run the length of Vermont. And you can join him.

Resilience: /rə’zilyəns/ n. 1. The capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness. 2. The ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity —Merriam Webster

On the first day of August, 2017, Pavel Cenkl ran steadily up a mountainside in Abisko, Sweden, in the pouring rain. Behind him, snowcapped mountains towered over Torneträsk Lake. He had just bid farewell to his wife, Jen, and son, Orion. Ahead, lay 800 miles of The Arctic Trail—and he planned to run 500 of them over the next 12 days.

Cenkl, a professor of environmental humanities at Sterling College in Craftsbury, Vt., had set out on his second long-distance run above the Arctic Circle. The first run, in the summer of 2015, was a 150-mile trek along western Iceland. These endeavors, part of an ongoing project he calls the Climate Run, were a chance for him to witness first-hand how climate change is impacting this delicate part of the earth.

In Scandinavia, summer conditions are usually mild. Temperatures typically range from the mid-50s to the high 70s. Government-sponsored travel sites suggest that hikers prepare for rain and wind. But Cenkl encountered something different. Within the first five kilometers of his trek, he ran through vast snowfields. Rivers ran high with snowmelt.

When he came to the first river crossing, he realized that the trip he had so carefully planned was going to be tougher, and wetter, than he anticipated.

“I was looking for a bridge,” he says, “But there was no bridge. There was just a snowfield that ended in a river. So I rolled up my running pants and stepped right in the water. Those are not August conditions.”

On the third day of his run, Cenkl got lost. Having camped in Sweden the night before, he crossed over into Norway, and was 25 kilometers deep into a section of overgrown trail. The flooding waters had submerged bog bridges and bridges over rivers. No one had recently cleared the path, and birch and alder slapped Cenkl as he ran through it.

Finally, he reached a big, open plateau where he could see the Swedish-Norwegian border. Before the trip, he had scoured what seemed like every inch of the trail by satellite, but with a malfunctioning GPS, he missed a trail junction and ran several kilometers in the wrong direction. Sensing his mistake, he dug into his pack and pulled out three different maps, trying to triangulate his location.

“I came across 100 yards of trackless bog, but on the other side of it, I thought I could see this faint little bit of trail,” he says. “So I traipsed through the bog, got to the other side, and there was a rock sticking up that had a hand-painted, abbreviated name of the hut that the trail was supposed to lead to. I’m like, ‘yes!’ That was the first trail sign I’d seen in 20 kilometers. So I knew I was on the way.”

It might have been relief, or adrenaline, but something about that moment that made Cenkl take pause. The shadows grew longer in the late-afternoon sun, and the air was silent. A line of cairns guided his way along a ridgeline.

“Somewhere online I published a photo of me waving, and you can see my shadow in the distance,” he says. “I even took a short video. I just needed to stop and somehow document this experience—I was fully connecting with this place. That was the highlight of the run, for sure.”

A few dozen kilometers later, Cenkl came to a larger river. He had done many river crossings that day, but when he examined the water from the river’s edge, he discovered that it might be impassible: a class II rapid. The river wasn’t supposed to be this high, but with all of the unseasonable snowmelt, he guessed it would be chest-deep.

It was getting late—Scandinavia was in a period of 24-hour sunlight—and he often ran until 10:30 p.m. His previous navigational blunder, along with the 55 kilometers he had already run that day, had made him reasonably exhausted.

Unproductive thoughts circled his head. I can’t do this, he thought. I’m going to have to turn back. Pacing up and down the side of the river, he started to panic. He swore at it, like some do, out in the middle of nowhere. He wondered why someone hadn’t built a bridge—there was a constriction, they could have.

Eventually, he took a breath. I’ve got to calm down, he thought. I’ve got to eat dinner. I’ve got to get some sleep.

In the tent, he searched his map. To avoid the river, he would have had to turn around and go back the 55 kilometers, down into a fjord, find the village, and take a boat that only goes there a couple of times a week. All of that—or he could cross this river, whose other side sat 50 yards away.

Cenkl fell asleep. He woke up at 5 a.m. and immediately noticed a difference: the river sounded quieter. He threw everything in his backpack and ran toward the river’s edge. It looked lower. I just have to do this, he thought.

He stepped into the now-waist-deep water, still a class II rapid. Though he felt completely at the mercy of the river, he began to move forward. Falling wasn’t an option: there was a bigger rapid downstream. Placing his poles strategically, he took careful steps and slowly worked his way to the other side.

“I was so exhausted and relieved,” he says. “All I could think was, everything is going to work out. I did this.”

And then he had breakfast.

BECOMING RESILIENT

In his teaching, Cenkl often talks about climate ‘resilience.’ He focuses on the idea that humans, and all life on Earth, must determine how to adapt in the face of challenge. Athletics, he says, helps him practice this concept.

“For me, endurance gets me to the place where everything else is stripped away. You so immerse yourself in the natural world that you are obviously a part of it,” he says. “Endurance athletics allows me to do that. You realize that the boundary you perceive between yourself and the world really isn’t there.”

Cenkl grew up in the White Mountains, where his parents put him on skis when he was three years old. His first long-distance running stint was a 52-mile ultra run through the Whites, when he was in college. He was working for the Appalachian Mountain Club at the time, and it was then that he first started to feel a deep connection to wilderness and a desire to preserve it.

Now, endurance racing is a regular thing for Cenkl. One of his favorite races is the Leadville Trail 100, a 100-mile race across the Colorado Rockies. He’s also a regular participant in the Green Mountain Skimo Race Series, and runs with his students in the Tarc Winter Ultra, a 40-miler just north of Boston, every year.

As Cenkl’s athletic resume grew to include cross-country, backcountry skiing and ultra-running, so did the link between endurance sports and climate resilience. Recreating outdoors allowed him to experience the remaining wild, to see the world as it might have existed before the Industrial Revolution set off a chain of atmospheric contamination, or before seven billion people reshaped the surface of the earth.

Athletes are dependent on the patterns of the natural world: snow in the winter, warm air in the summer, April rivers bustling with freshly melted snow. As Cenkl sees it, the natural world is dependent on athletes, and non-athletes, to preserve a world they so love.

“Once, we recognize that the system is so complex, how can we, with good conscience, continue the way that we’re going, in terms of affecting the climate in a negative way?” he asks.

The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. Temperatures there have increased by as much as 7.2 degrees in the last 50 years, according to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment. Chunks of sea ice equivalent to the size of Norway have melted away.

Cenkl visited Norway and Sweden in August, when he expected snow to be absent. Instead, he found giant snowfields that were melting, causing rivers to overflow. As a result, many sections of the trail were difficult to navigate.

While the unusually cold temperatures probably weren’t a symptom of climate change, Cenkl thinks the unusual size of the snowfields might point to the extra 25 percent of precipitation the Arctic has experienced in the last century. “The seasonality was all askew,” he says. “They were five weeks behind their regular snowmelt. The trail was much more difficult as a result of that. I think that that puts a fine point on, ‘it’s not global warming, it’s climate change.’”

TIME TO RUN

TIME TO RUN

The Climate Run idea was born during Cenkl’s early years at Sterling, where he’s also director of the school’s athletics program and the coach of the trail running team. At the small college, home to just 130 students, Cenkl has found an intellectual sweet-spot where he can discuss climate resilience issues with students while they run together through the college’s 390 acres of forest.

Soon, he wondered if he could engage with the public on a similar level. A plan began to form: he would embark on an adventure in a region of the world that was particularly affected by climate change. By doing so, he could spark discussions with students, scientists and the public in the process. What better place than the Arctic?

With that, he set the plotting in motion. He made his own route for the 2015 run through Iceland, charting out the 150 miles on Viking trails, dirt roads, and open tundra. In Scandinavia, he discovered the Arctic Trail, which made things a bit simpler.

The trail winds for 800 kilometers down the border of Norway and Sweden. It passes through four national parks: the Øvre Dividal National Park, Reisa National Park, Abisko National Park and Padjelanta National Park. With huts along the way, Cenkl decided it was possible to run 500 miles of the trail, starting at its northernmost point in Abisko, Sweden, and ending in Sulitjelma, Norway. The entire run took place above the Arctic Circle.

Once the plans were set, he started to train. In Scandinavia, he planned to run 50 kilometers per day for 12 days. At home, he prepared by slowly increasing the number of miles he ran until he hit 80 miles per week. “I would do longer runs over the weekend, or back-to-back longer runs,” he says. “They might be 15 miles one day, 25 the next.” He sprinkled the regimen with ultra marathons, 50-kilometer runs and 50-milers.

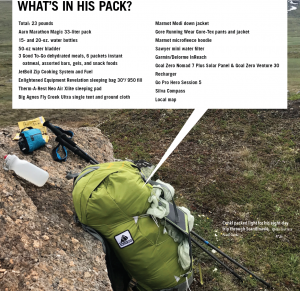

With light traveling in mind, he bought an Aarn pack and filled it with only the essentials—several days’ worth of dehydrated meals, GPS and communication supplies, lightweight clothing, a one-pound tent—and tested it out on a 20-mile out-and-back Monroe Skyline section of the Long Trail. Fully loaded, the pack weighed 23 pounds.

Finally, Cenkl connected with scientists in Scandinavia. When the run was complete, he wanted to relay their research on his blog and in presentations to folks back home. He reached out to Alexandra Messerli, a glaciologist with the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, and Mads Forchhammer, a biologist at the University Center in Svalbard, Norway, who studies reindeer.

He had thought these connections would help him learn about climate change in the Arctic. Instead, he gained most of his knowledge about the far north’s changing conditions first-hand.

LOOKING FOR A SOLUTION

Cenkl didn’t finish the run. He checked out on day eight, at the 360-kilometer mark. The snow and flooding combined with a stress fracture on his left shin had become too much. “I just thought, ‘this is not going to be useful or fun,” he says. “If I have to wince in pain every time I have to take a step, and I’m not going as fast as I want to or covering the distance, then I’ll come back another time.’”

When he came home, Cenkl gave presentations around Vermont, and around the country, about his time in Scandinavia. At the end, he would open the floor for questions. A few popped up over and over. He was most commonly asked: “What was your favorite part?”

“The first time I was asked that, I stopped and said, ‘Actually, having this conversation right here,’” he says. “The more I think about that, the more that is actually my favorite, and perhaps the most important part of what I do—having the opportunity to share the stories and maybe inspire people to go do similar things.”

But there’s a much harder question asked by both adults and kids: “What’s the solution?”

When Cenkl first started thinking about the Climate Run, he wanted to focus his discussion on athletic endeavors. How could athletes recreate in a way that reduces their carbon footprint? How can the athletic community keep climate change in mind when carving trails, buying equipment and traveling around the world?

“It’s hard to reconcile,” he says. “I got a bit of criticism, as you might expect. People said, ‘You’re flying to Iceland to bring attention to—climate resilience?’ And I thought, well, that’s true, however, none of us can really bear up to that sort of scrutiny. Simply by living where we live, by being Americans in the twenty-first century, our ecological footprint is so vast. I asked myself, ‘Is it worth an air flight if I’m going to be able to talk to a thousand middle and high school students about building climate resilience? How is that going to inform my teaching, and how many people will actually be affected by those stories? I started thinking, it’s not really about the individual choices. Those are important, too, but it’s much more about making change on a much broader, systemic level.”

While he admits those thoughts are still on his mind, and still an important part of the conversation, the discussion has become broader.

“And so my answer is that it’s really about building community,” he says. “I think that’s a little eye-opening for people who thought they could just recycle and it would make things all better. You need to have a get-together with your neighbors and talk about how you’re going to live together in this world that’s changing.”

CLIMATE CHANGE AT HOME

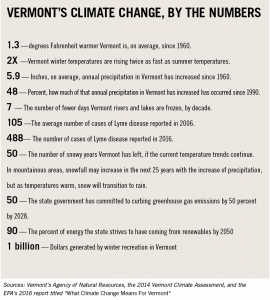

Cenkl’s runs might have focused on the Arctic, but in his own backyard, the climate is changing fast. Vermont is warming at almost twice the speed of the rest of the country, and winters are affected the most. “I think it’s obvious when we look outside the window now,” Cenkl said on a snowless day this January, “winters are a whole lot shorter.”

During the winter of 2015-16, the warmest winter in all 121 years of record keeping for the United States, Vermont received half its normal snowfall. On the whole, the state continues to see snow, but that doesn’t surprise climate scientists, who say Vermont may see even more snow than usual in the next 25 years, due to the 5.9 additional inches of precipitation, on average, that Vermont has gained since the 1940s.

During the winter of 2015-16, the warmest winter in all 121 years of record keeping for the United States, Vermont received half its normal snowfall. On the whole, the state continues to see snow, but that doesn’t surprise climate scientists, who say Vermont may see even more snow than usual in the next 25 years, due to the 5.9 additional inches of precipitation, on average, that Vermont has gained since the 1940s.

Don’t be fooled: temperatures are still warming. Eric Kelsey, the research director at the Mount Washington Observatory, has been studying the trends.

“If it warms by 4 degrees here, which it has over the last 40 years or so, it’s still cold enough for snow,” he says. Compared to a human lifetime, the warming is slow.”

According to a 2011 study by the state of Vermont’s Agency of Natural Resources, titled Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Recreation in Vermont, “By the end of the century, the average number of reliable snow-covered days in the Northeast is expected to decrease to as few as 13-25 days.”

“From a recreation perspective,” Kelsey says, “what really stinks is that we’re getting more warm spells. I call it the Swiss-cheese-ification of winter. If winter is the cheese, we’re getting holes punched in it by warm weather.”

The ski industry has felt the warmth: many Vermont resorts have invested millions in snow-making systems so they can recover from melting events in a matter of hours. But if global emissions aren’t curbed, Vermont’s temperature could rise between 3.6 and 9.7 degrees more by 2050. Winter would be cut short. Without snowfall during the holiday season, for example, ski resorts could lose as much as a third of their revenue.

The warming trends bring on a host of other ecological consequences. For wildlife, the possibilities are endless: invasive species are more likely to overtake native plants, pests will migrate north, and the temperatures would likely create an uninhabitable ecosystem for some native plants, like sugar maples.

To an extent, these consequences have already taken hold: Moose are dying from an onslaught of winter ticks. Scientists often find their carcasses covered with tens of thousands of the parasites. Deer ticks have prevailed where there once were few: In 2006, 105 cases of Lyme’s Disease were reported in Vermont. In 2016, 488 cases were reported.

Cenkl says it’s too late to resist these changes.

“You can’t just say, ‘the sea levels are going to rise, so let’s build a wall around Manhattan so that we can continue as we are,’” he says. “You have to accept the fact that things are going to change. How do we then change our economy, our systems, our education, to meet this changing world?”

But resilience takes work. It requires entire populations to come together and look the impending change straight in the eye. Then comes the muscle power: sizing up the changes and developing an intelligent, comprehensive understanding of how they can best be addressed.

That’s why, this summer, Cenkl is hoping to bring the Climate Run to Vermont. In June, he plans to complete the Vermont 100-200: bike Route 100 from the Canadian to the Massachusetts border. Then, he’ll run the 273 miles of the Long Trail. Until now, he’s run alone, but this time, he’s inviting people from around the state to join him and engage in a conversation about climate resilience.

“Who are the people, and what are the organizations in Vermont, along the spine of the Green Mountains, that are participating in building a climate resilient community?” he says. (Check vtsports.com for updates about the run.)

On the run, he hopes to check the boxes of all of his collective missions: bringing together a community, discussing climate resilience, and most of all, pushing himself on the very trails he’s looking to preserve.

Top photo by Jill Fineis

This story was originally titled “Running for Resilience” in the 2018 March-April print magazine.

Pingback: Vermont Sports Magazine, March/April 2018 - Vermont Sports Magazine