Paddling the ADK’s Lost Ponds with Bill McKibben

The Adirondacks are riddled with quiet waterways and Lost Ponds. This may be the perfect way to find them. Plus, the perfect craft for on a paddle through these ponds.

By Bill McKibben

Months with the novel coronavirus on the loose have taught us all sorts of new tricks: not only can you Zoom, you can manage the background on your Zoom image. Everyone with a sewing machine has figured out how to make a mask. I can wash my hands like a surgeon.

But let me tell you about one more tool that’s absolutely perfect for the moment we’re in. A Lost Pond solo canoe, built by Pete Hornbeck at his small shop in the central Adirondacks, is pretty darned good almost any time—I’ve had mine for 35 years—but these last weeks have revealed a whole new beauty.

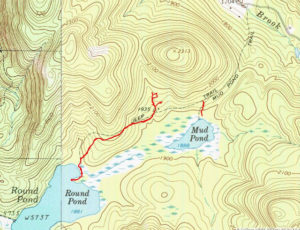

In mid-June, I set out to paddle from one of the ‘lost ponds’ that Hornbeck designed the boat to serve, to another lost pond, and back again. These ponds—just south of Garnet Lake, and near my home in North Creek—are not charismatic bodies of water with romantic names and histories.

In fact, they’re so uncharismatic that one of them is called Mud Pond, and the other is called Round Pond. (The first name, as you shall see, is entirely apt, and the second at least approximate).

I left my car at the DEC trailhead by the first of these and hiked perhaps a quarter mile down a path to the water.

The Hornbeck weighs 15 pounds, which means you can rest it easily on your left shoulder, almost as women once slung a handbag—with your right hand you can carry your carbon fiber paddle ready to push through brush if necessary.

Once at water’s edge, you float the boat and then, with some care, put one foot inside, sink your butt onto the foam seat on the floor, and shift your weight to bring your other foot inside. It has what I believe boatbuilders call ‘low initial stability,’ meaning it’s a little tippy to get in to. But once you’re inside, it couldn’t be more stable. You use a two-bladed kayak paddle, resting your feet against braces mounted inside the hull that allow a surprisingly easy and powerful stroke. It handles chop up to a foot without any trouble—I’ve taken it through larger whitecaps, but in those I confess I hug the shore.

This day, there was no wind and no problem. I was across Mud Pond in minutes, reaching its western edge where a beaver dam raised the level of the water. I clambered out, hauled the craft easily across the dam and the 18- inch drop on the other side, clambered back in, and proceeded.

About eight feet further I had to undergo the procedure again. Lather, rinse, repeat. The channel was impossibly narrow in spots, though when I got out to pull the boat between the reeds, it was also remarkably deep— often up to my chest.

I can think of no other boat I could have pushed, pulled, tugged and rassled through the next four or five hundred yards; it took me a fair part of the afternoon, but all of it enjoyable in its way, and then the prize: I was in the open, meandering flow between Mud and Round, perhaps half a mile of absolutely still beauty.

The grass was hardly higher than the freeboard of the boat, and a red-winged blackbird chittered on every stump. Dragonflies danced by the thousands, and when I stopped paddling I could hear the constant chortle of frogs. Just to lean back and watch the afternoon clouds float patiently by was pure joy. At the end of that half mile, a 40-foot carry put me on Round Pond, where deer shyly watched from the woods by a sandy beach, and where I placidly paddled in circles thinking deepish thoughts. A good place to camp, for sure, with very little chance of being bothered by another human. The virus and its attendant traumas seemed far away.

The return voyage, however, was a reminder that there’s more than one form of bother. It went just fine…at first. As I retraced my wake through the beautiful, nameless flow, a loon came charging by directly overhead, beating what always look to me like impossibly stubby wings for all it was worth. It was a reminder of just how predictably sweet the Adirondacks are, especially for those who like to paddle: water collects on this great dome, and its classic trips—the Seven Carries, say—are nonpareil.

I took this little Hornbeck on a fourday saga once that ended at Lake Lila; it’s the aquatic equivalent of a mountain bike, and it can carry you into heaven… or, conversely…the other place.

For that difficult final 400 yards back to Round Pond, I went to the left instead of following the same narrow watery track that had gotten me there. I thought it might be easier, and for a few minutes it indeed seemed wider— but then it began to crowd in, and soon I was out of the boat, leading it like a horse on a halter. But this time we were in truly epic mud—again and again I sank in well above my waist in clinging muck, and didn’t find much bottom. It was a tad unnerving.

But now my trusty boat was like a plank for someone trapped in quicksand—I’d lay my chest across it, and lever myself out, and then begin again. (One hiking sandal now rests somewhere in that bottomless mire.) But we persevered, boat and I, even though the black flies had begun descending, and eventually—brown with mud and flecked with a bit of blood from the bites—I was back on the pond, and then at the put in, and then hoisting the airweight boat back on the car.

No other boat that I know of could have made this trip—you couldn’t have hauled a Grumman or even a Wenonah as easily over those endless checkdams, and anything longer than ten feet couldn’t have made the endless three-point turns required to maneuver through those cramped lanes of grass and shrub.

Which means, depending on how you look at it, no other boat could have gotten me in as much trouble or in as much joy. Gotten me in, that’s the thing. In deep, in the real world, which is where we want to be right now. This trip was the opposite of Zoom—it was focus.

Vermont-based author, educator and activist Bill McKibben has been exploring the Adirondacks for more than 35 years. He is the author of The End of Nature, Falter, and numerous other works.

To read about more paddling adventures, read our articles: 3 Epic Paddler’s Trails and A Weekend in the Saranacs

A Hornbeck History

The Hornbeck design is based on a historic canoe, built in the 19th century by famed boat-builder Henry Rushton. He had a client, an outdoors writer named George Washington Sears. That was his real name, but most people knew him by his nom de plume, Nessmuk. (He’d borrowed it from a Native American he’d known in his youth, who taught him outdoor skills. That makes it a pretty perfect example of what we’d now call ‘cultural appropriation.’ But this was then.)

Anyway, Sears went to work at age 8 in a cotton mill, which may explain why he liked the woods so much—he grew up to write for Forest and Stream, and when he wanted to undertake a long voyage through many of the Adirondack Park’s 3,000 lakes and ponds, he convinced Rushton to build him a boat that would make for easy carries from one remote pond to the next. Since he only weighed 110 pounds, Rushton could go super-light. The resulting craft, made of white cedar with elm ribs, weighed 10 and a half pounds, and worked like a charm.

Nessmuk christened his craft the Sairy Gamp, for a Dickens character who ‘loved her gin straight and never took a drop of water with it.’ The boat, too, never took in a drop of water, or so its owner claimed; Rushton, meanwhile, soon had the delicate problem of explaining to many well-heeled customers that they were…slightly too big for the craft.

He went on to build many other ultra-lights, all of them slightly bigger—you can see many of them in the boat room at the Adirondack Experience museum in Blue Mountain Lake, but not this summer because it’s closed because you know why.

Anyway, about fifty years ago a local high school teacher named Pete Hornbeck started figuring out how to build a knockoff of the Sairy Gamp. He eventually settled on Kevlar, the stuff in bulletproof vests, as his standard, though now of course there are also carbon-fiber versions. His most basic model is roughly the same size as Rushton’s boat, about ten feet. It weighs about 15 pounds, and it can handle paddlers who weigh up to 200—beyond that there are now a whole range of craft, some with slightly sleeker and faster designs, but all designed to be easily portable and highly rugged. Good, that is, for crashing through the woods in search of isolated sheets of water. Good for right about now.

Pete Hornbeck’s son in law, Josh Trombley, who now handles the business end of the operation, reports that sales are brisker than ever during the pandemic. You need to call their Olmstedville headquarters and book an appointment for a visit— there’s a pond there to try the craft before you buy. Which you almost certainly will. Because there’s never been a better time to go off by yourself in a little boat and muck about.

Head to Hornbeck’s site to learn more about their products which are perfect for exploring lost ponds.

I have always feared mud that deep, specially since I do love the adventure of the unknown places…Well said Bill M. And yes i just got my first Hornbeck!! A mere 18 lbs. Love at first paddle.