Climbers On The Rise

As climbing becomes one of the fastest growing sports in the country, Vermont is keeping pace with a slew of new indoor climbing gyms.

Three hundred feet above the ground, Burlington’s legendary climber Peter Kamitses presses his fingertips into a crack on a sheer cliff face. His heavy breath breaks the air’s silence, and his helmet bobs as he looks up and down, examining the rock. The toe of his black climbing shoe taps the cliff in a wide arc, searching for any nub to support him as he pushes upwards. No luck.

His arms begin to tremble. His breath gets louder. The entirety of his body weight is held up by his right foot, pressed with friction’s grip against the almost-featureless crag. “I’m out,” he calls to his climbing partner, who is standing over a hundred feet below.

His right toe skids. Kamitses’s body slips from the wall and he falls, down, down, three long seconds down. Halfway to the ledge, his rope—a ridiculously frail-looking lifeline—snatches him upwards. He screams as his feet bounce off the rock. Dangling for a moment, he screams again—this time in ecstasy. He is safe, having lost only distance and the progress it represents.

Most climbers who have visited this site, Moss Cliff in the Adirondacks, were aid climbers. For over a decade, Kamitses has been free climbing this face. He uses only his body strength, unsupported, to ascend the routes, but is protected by a rope that’s anchored down the cliff.

For the past few years, he’s been working to establish a new route that no one has ever climbed before. When he’s done, it will likely be rated a 5.14b—the hardest ascended climb in the Adirondacks. He’s calling it “The Lifeline.”

“If you ask any climber, ‘what’s the beta?’ you’re asking them, ‘how do you do the route?’” he says. “The process of refining beta—that’s addicting for me.”

Kamitses fell in love with climbing in the 1990s while on a pre-college trip to Australia with a friend whose father had scaled the big walls of Yosemite. Later, while studying at University of Vermont, he began climbing New England’s rock faces, where he has had many of his most memorable learning experiences.

Now, he’s well-known for being the first to ascend some of the most difficult climbs in the Northeast, including Oppositional Defiance Disorder, a 5.14 in the Adirondacks, and Vermont’s two hardest climbs: The Hardway, a 5.14a, and Stoning the Fascist, a 5.14b, both at Marshfield Ledge.

Summer will find him climbing around New England, but at this time of year, your best chance to catch him in action is at one of Vermont’s growing number of climbing gyms, including Burlington’s newest gym, MetroRock Station, where he is a co-owner.

Scaling New Heights

When Kamitses first started seeing walls as recreational playthings, outdoor climbing was a sport reserved for the extreme athlete, and indoor climbing gyms were far less popular. Gyms allowed outdoor core climbers to keep their fingers chalky in the off-season. Otherwise, they were kids’ birthday party venues, visited only occasionally by athletes looking to get fit.

Now, rock climbing is one of the fastest-growing sports in the country. Close to 4.6 million Americans climbed in 2015, according to a report by the Physical Activity Council. Popularity-wise, it’s overtaken traditional sports like gymnastics and track. And while the sport collected fewer than 20,000 newcomers between 2007 and 2014, from 2014 to 2015 it grew by a whopping 148,287, accruing 130,000 more climbers in a single year than it had in the previous seven.

Climbing gyms have been a big part of that growth. And Vermont, among the healthiest states in America, is no exception.

Three climbing gyms—PetraCliffs in Burlington, and Green Mountain Rock Climbing Centers in Rutland and Quechee—have hosted Vermont’s climbers long before the sport was trendy, and some for over a decade.

While the veteran gyms are still going strong, new facilities are cropping up around the state, proof that Vermont’s climbing community is on the rise.

MetroRock, part of a chain of gyms connected to their main hub in Boston, opened in August of 2014, at the height of the popularity explosion. After working as PetraCliffs’s route setter and traveling to set routes in different gyms across the Northeast, Kamitses spearheaded the decision to open the new gym with a push from MetroRock owner Pat Enright. He felt that Burlington’s growing cadre of climbers was stunted by the existence of only one local gym.

“It was a no-brainer. Someone should have done it a decade ago,” Katmitses said. “And the owners of PetraCliffs, Steve and Andrea Charest, they’re still doing great. So there was room for a bigger gym, as well as the other gym to still exist. Friends of mine, a lot of them, climb at both gyms, and one of the route setters for me sets there as well. So there’s plenty of room.”

Several Vermont ski resorts have installed climbing facilities, as well. In the summer of 2016, Stowe opened an indoor climbing center called Stowe Rocks as part of the Spruce Peak Adventure Center. It features a bouldering area and 16 top-ropes, each with three to four routes, which vary in difficulty.

Smuggler’s Notch recently installed its 26,000 square foot Fun Zone, home to a double-sided 30-foot climbing wall. You can find smaller rock walls in hidden corners all around the state—for example, Sugarbush Resort is home to a wall, which is part of the Sugarbush Health and Racquet Club, and The Edge, a fitness center in Williston, has a rock wall that is free to use for gym members.

In 2017, a group of Southern Vermont climbers opened a bouldering gym called the BrattCave in Brattleboro. The gym is housed in the Cotton Mill, a large brick building that houses over 60 artisans and small businesses—including the New England Center for Circus Arts. Though Tom Mizrahi, an organizer, says there isn’t a huge climbing community in Brattleboro yet, he hopes the gym well get potential climbers excited.

Meanwhile, the state’s long-serving gyms are expanding programs and seeing new members. Steve Lulek, owner of the Green Mountain Rock Climbing Centers in Rutland and Quechee, started SIRCA, the Scholastic Indoor Rock Climbing Association, which has recruited 39 area middle and high schools that now offer rock climbing as a team sport. He also sees out-of-state visitors much more frequently now than ever before.

“We’ve seen an up-tick in the summer, and a little bit in the winter when skiers are here, because climbing is becoming more normal in the big cities,” Lulek says. “People are here from New York skiing, and then afterward they’ll come down and get in a couple of climbs because they’re part of a gym down in their own city. We’re seeing that now where we’ve never seen it before.”

PetraCliffs co-owner Andrea Charest says that along with those who attend PetraCliffs’ thriving summer camp and mountaineering program, thousands of visitors walk through the door each year.

Now, that gym is looking to expand as well. “We’ve been looking for about two years for a new building to grow,” she said. “We want to modernize things a bit while keeping the same feel that we have. There’s definitely a different feel here than at other gyms—just that warm community feel.”

With more than 400 commercial climbing gyms popping up around the country, and many, like PetraCliffs, looking to expand, rock climbing’s sudden explosion might be more than a trend.

Many youth programs, like Lulek’s, are becoming more popular, and kids are growing up having incorporated climbing into their lifestyle. “It’s accessible for them,” Kamitses says. “With a lot of sports, there is a super high level of skill needed. You can’t just go play tennis or golf or something like that—you’re not going to have a good time if you’re not an athlete, or you’ve never tried it before, and then you’re not going to want to go back. Indoor climbing is going to give you a taste of success. So it hooks people.”

Though Kamitses and many other long-time climbers would take outdoor cliffs over ‘pulling plastic’ any day, indoor climbing has been responsible for most of the boom. Much of the growth can be attributed to millennials living in urban areas, the Physical Activity Council report says, and many of them will never make the transition to the outdoors.

“Some people never climb outside,” Kamitses says. “They go into climbing gyms because it’s super fun. It’s a social atmosphere, generally, because you do one full-out effort on a 50-foot indoor wall, and then you need to rest for 20 minutes. So you hang out and talk to other people and belay your friend.”

The Mental/Physical Challenge

One of the appeals of climbing is that it involves both mental and physical gymnastics. Ascending a wall requires climbers to push fear away, work through a puzzle and, ultimately, quiet the mind.

“It cuts everything out of your brain, and it’s like forced meditation,” Kamitses says. “It’s a super universal thing to be scared of heights, because if you fall from high and hit the ground, that’s bad. Every human gets put into this heightened state when you put them 40 feet up on a ladder, let alone a vertical rock wall. You’re going to be very aware of what you’re doing.”

If the mental challenge makes up half the appeal, physical fitness takes the rest. Lulek first discovered the lure of climbing when he started and ran a mountaineering school for military and National Guard personnel in Jericho, Vt.

Since then he’s taught outdoor phys ed classes at Castleton College and UVM, and he teaches a twice-weekly class called ClimbFit, which combines cardio, climbing and muscular development, at his Rutland location.

Lulek tries to get newbies to see climbing as a “functional fitness” activity, meaning it both originates from and promotes natural movement. He uses bouldering (a type of climbing practiced without a rope on artificial “boulders,” which are low to the ground) for most of the class’s workout.

“People who climb two to three times a week at the gym, if they took their shirts off, you’d just see all these abs,” Lulek says. “It’s the external obliques that really get used, and a little bit of the six-pack, and all of the core stabilization muscles.”

At first, climbers typically over-depend on the forearm muscles, but after sticking to the sport for a few weeks, they begin to use the shoulder muscles—the anterior, medial and anterior deltoids—when pulling themselves from hold to hold.

Accomplished climbers have a good balance of definition in the quads and hamstrings. Lulek says, unlike the workout you might get from working on a machine, climbing promotes “real strength.”

“If you take an old Vermont farmer—he may have a belly on him, but that guy has moved real things, creating total muscular strength tendons and ligaments,” he says.

“All the joints are strong. That’s what happens with climbers. You’re not just developing the muscles, you’re developing the tendons and ligaments—and they’re pulling in all directions. If you go to a regular gym, you do the repetitive bicep curl, but when you climb, your bicep is working at all angles.”

For Kamitses and others, climbing is almost a form of mental and physical therapy. “When you’re climbing, it’s just instant focus. Every bit of clutter and clatter in your brain goes away, and you’re only thinking about what’s going on right in front of you, the next hand moving,” he says.

Kamitses adds: “After a long day of climbing, my brain feels refreshed in a different kind of way because I haven’t had that monkey mind running around, and thoughts of all the other bullshit in life—problems with relationships and work and blah blah blah. In that way, it’s therapeutic.”

Luckily for Vermonters, there are great climing gyms within an hour’s drive of most corners of the state. Most of these gyms will rent you equipment (shoes, harness, safety gear, chalk) for a fee of $5 to $10.

Where to Climb The Walls

PetraCliffs, Burlington

(Update 4/6/18: PetraCliffs is expanding. Click here for details.) Andrea and Steve Charest bought PetraCliffs in April of 2012, but their history with the gym started long before. Steve, who studied Outdoor Education while attending Johnson State, started interning with PetraCliffs in 2001, and he was on the committee that hired Andrea a few years later. The two fell in love with climbing—and each other. They married and now have a climber-baby six months on the way.

And the gym seems to be the perfect place to raise a child—or to find your inner child. The 26-foot-tall walls hold lead climbing, top rope terrain and over 44 routes ranging from the easiest 5.5’s to advanced 5.13’s. The separate, 14-foot-tall bouldering stations hold 64 boulder problems that range from a V0 to v10+.

Andrea and Steve attest to the close-knit, family-friendly atmosphere that the gym seems to be founded on. “You can be climbing next to a four-year-old on one side and a world-class climber on the other,” Steve says. “It’s that kind of blending of the community, where it doesn’t matter, your skill level. You’re right next to each other.”

An adult full-day pass at PetraCliffs costs $18 and includes all types of climbing, while bouldering passes are $13. Monthly memberships start at $65 for adults.

The PetraCliffs experience extends far beyond the gym. With a full mountaineering school, PetraCliffs guides lead outdoor rock and ice climbing trips, backcountry skiing and avalanche training. (Prices range from $100 to $245, depending on the number of people attending). petracliffs.com

MetroRock Station, Burlington

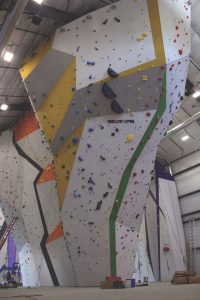

Inside Burlington’s newest rock gym, climbers dangle from nearly 60 top ropes, draped down 50-foot faces. The faces hold more than 110 routes, which range from kids’ level at 5.4’s to 5.13’s. A giant tower set squarely in the center is the main station for top rope and lead climbing, and behind it, groups of boulderers gather near the top-out wall (which includes a space to sit once you reach the top), called the “Whale’s Head,” to cheer each other on. The gym boasts 4,000 square feet of bouldering terrain.

Toward the back of the gym, climbers can practice their balance on a slackline, and lower walls with five auto belays create a safe climbing space for kids. Upstairs, a 35-degree bouldering wall called “The Beastmaker,” complete with ice holds, helps outdoor and ice climbers train for extremes.

A day pass at MetroRock starts at $20, and for those who want to keep coming back, memberships start at $75 per month with a $29 activation fee. The gym offers an “Intro To Climbing” class, in which instructors teach new climbers basic technique and how to belay safely. MetroRock also offers weekly yoga classes, which are free for members and cost $5 for non-members, and an adult clinic, which meets once a week and integrates core exercise and fitness into a set climbing regimen.

The gym is designed entirely by Kamitses, who traveled to Bulgaria to lay out his plan with the largest wall manufacturer in the world, called Walltopia. “I designed every wall, angle and panel,” he said. “It was kind of a dream come true. I was like a kid in the candy shop.” Kamitses is also MetroRock’s lead route setter, so he’s constantly thinking about the placement of holds to create challenging and rewarding climbs for all levels of climbers. Kamitses says he changes the routes every week.

“Basically, we’re refreshing the challenges of all abilities. So you get to be super creative. You build movement for climbers.” metrorock.com/burlington

Green Mountain Rock Climbing Centers, Rutland & Quechee

In 1996, Steve Lulek peeked into the building that is now Rutland’s Green Mountain Rock Climbing Center. Up in the left corner, the newly-established gym’s owner, Josh Bruckstein, was working away on construction. Lulek walked inside and asked for the man’s name. “My name is Josh, and this is my gym,” Bruckstein said, to which Steve replied: “I’m Steve, and I’m going to own this gym one day.”

Bruckstein angrily told Lulek to leave, but over time, the two developed a friendship and Lulek has now owned the gym for 14 years. Five years ago, Lulek acquired another gym in Quechee.

The Rutland gym has 30 top ropes that drop down 30 feet. Each rope has several routes, which range from 5.5 to 5.13. Quechee’s gym holds 26 top ropes, and the walls rise 45 feet. Currently, you can boulder the bottom section of all the walls in Rutland’s gym. In 2017, a new section will dedicate an entire side room to bouldering.

While the climbing options are extensive, the gym’s best quality is the staff’s eagerness to teach. Matt Digan, general manager at the Rutland gym, says “We’re always out on the floor giving tips on technique, whether they’re to first-time climbers or people who have been coming here for years.”

Along with the casual instruction and Lulek’s SIRCA program, which allows school-age students to climb as a team sport, Lulek’s ClimbFit classes allow veteran climbers and newcomers to use climbing as a fitness tool. The class, which is offered Tuesdays and Thursdays, uses bouldering and cardio. It usually involves working with a weighted jump rope, core training on a stability ball, leg routines with squatting, and finally, 30 minutes of lead climbing.

For those looking to climb for fun, the gyms offer adult leagues, which take place from September to November, and from January to March. “We meet on Thursday night, we have a great time climbing, we submit scores, and then everybody goes out for post-climbing beers and appetizers and stuff like that,” Digan said.

A day of climbing costs $18 at both gyms, and memberships start at $45 per month plus a $25 start-up cost. vermontclimbing.com

Stowe Rocks & Smuggs’ Fun Zone

Sometimes you need a break from the slopes, but want to keep your muscles active. That’s why many resorts now feature slope-side climbing gyms or walls.

In summer 2016, Stowe Mountain Resort opened Stowe Rocks at the heart of the new Adventure Center at Spruce Peak Plaza. At the center is a 40-foot tower that rises in front of windows that face the slopes and a 12-foot high bouldering wall. The center’s 50 routes, some of which are modeled after outdoor climbs at Smuggler’s Notch, are designed for climbers of all abilities, and include both bouldering and top rope terrain as well as eight TruBlue auto belay stations.

Best, you can grab a pizza or burger at The Canteen and still watch the action. Day passes are $37 ($31 for kids) and include equipment and a beginner’s climbing class. Season passes are $450, and $280 for residents of Lamoille, Washington and Orleans counties. stowe.com

Just over the mountain, the folks at Smuggler’s Notch installed a new 26,000-square-foot Fun Zone, which includes a double-sided, 30-foot rock wall (along with a laser tag arena, mini-golf, and a slot car track) in 2017. smuggs.com

Pingback: PetraCliffs Plans Expansion — Vermont Sports Magazine